In recent weeks, I have been glued to the tube. I am watching the House of Representatives and their questioning on the problems in government implementation of policy. I listen back to all the interviews at double the speed as I walk around the neighborhood. The hearings cover both the major issues at the Temporary Committee on the Implementation Organizations and very specifically the child care benefit scandal.

Yesterday I listened to our boss of all, Prime Minister Mark Rutte. He was referring to Ms. Palmen’s memo, which was questioned a week earlier. In that 2017 memo, she raises the alarm to her management team and writes in plain language that something bad is going on.

Rutte called that memo a whistleblowers alert.

I was startled. By saying that, he is basically saying that if you disagree with your manager and hit the emergency brake hard, you are a whistleblower. That when you provide unwelcome feedback to colleagues and managers neatly through the official process, because that is what a memo is, just internally in your own organization, you are a whistleblower.

As a public servant, you would rather not be a whistleblower. That’s really not a fun role and might come back to bite you later.

I know this because I am a public servant myself and regularly go back to my organization with difficult feedback from citizens. I am one of thousands of officials in the “implementation proces”.

Understanding and yet misunderstood

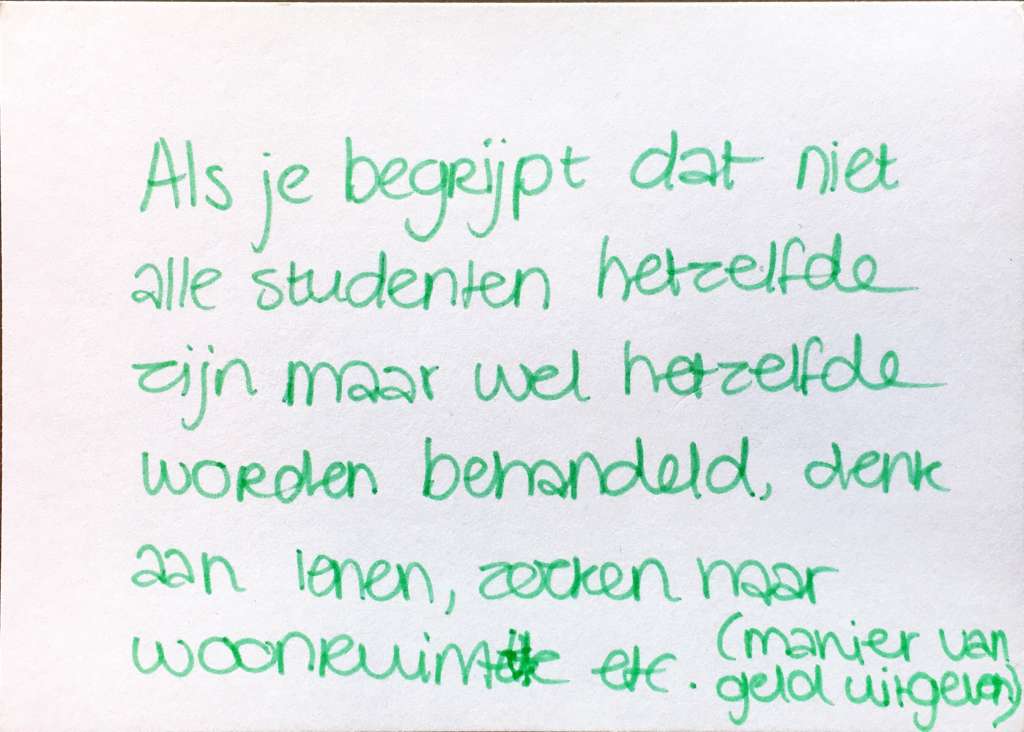

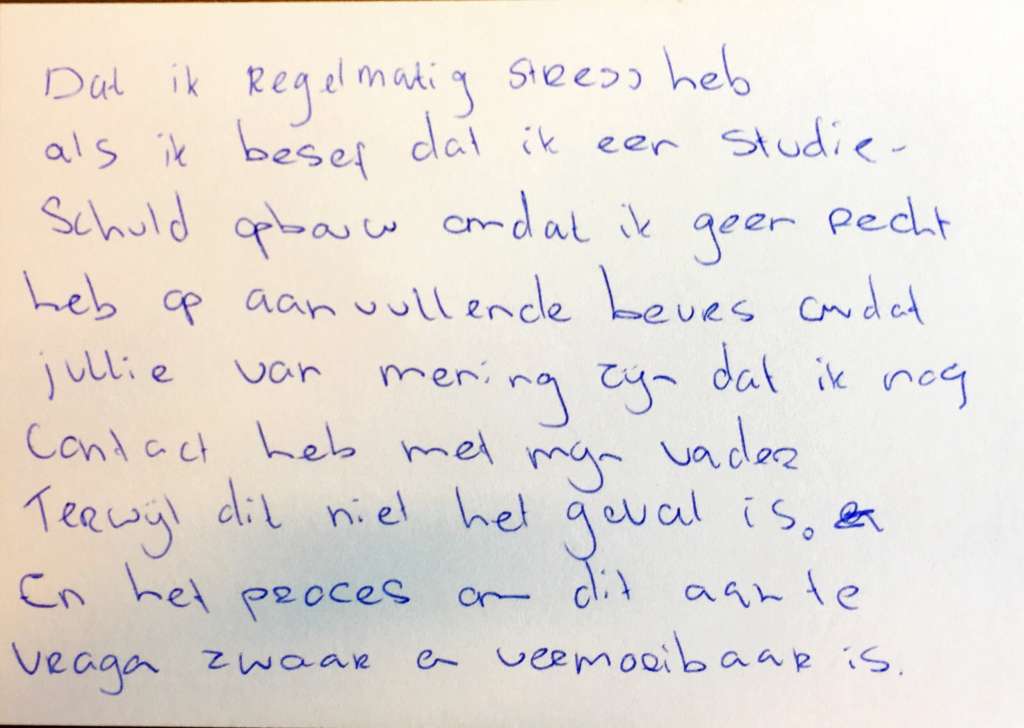

I work at Uncle DUO (as students sometimes call the Executive Agency of Education), and it’s my job to find out how students, citizens and school employees experience our (digital) services. I think my work is super. I get everywhere, even into people’s homes, and I hear the most wonderful stories. And sometimes the saddest stories of people who feel misunderstood.

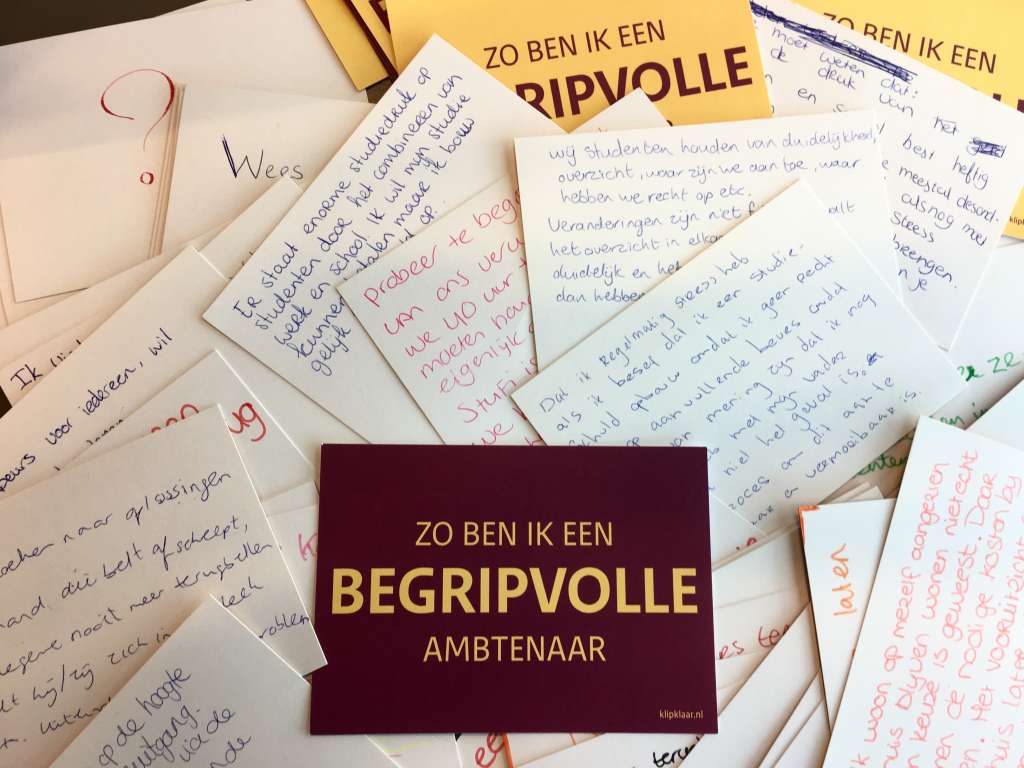

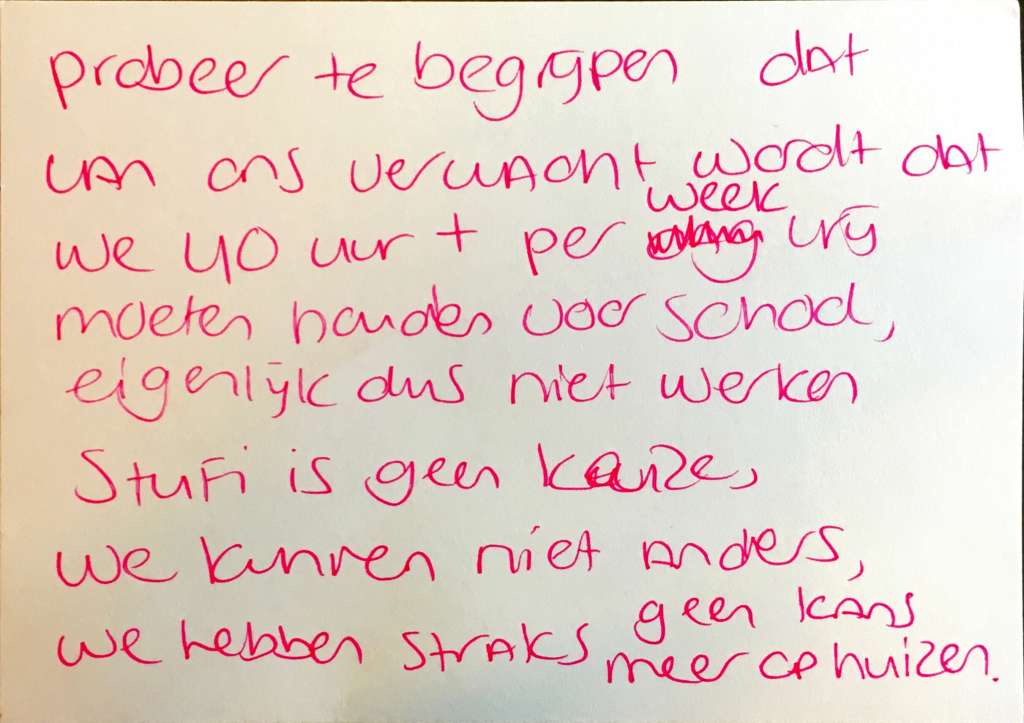

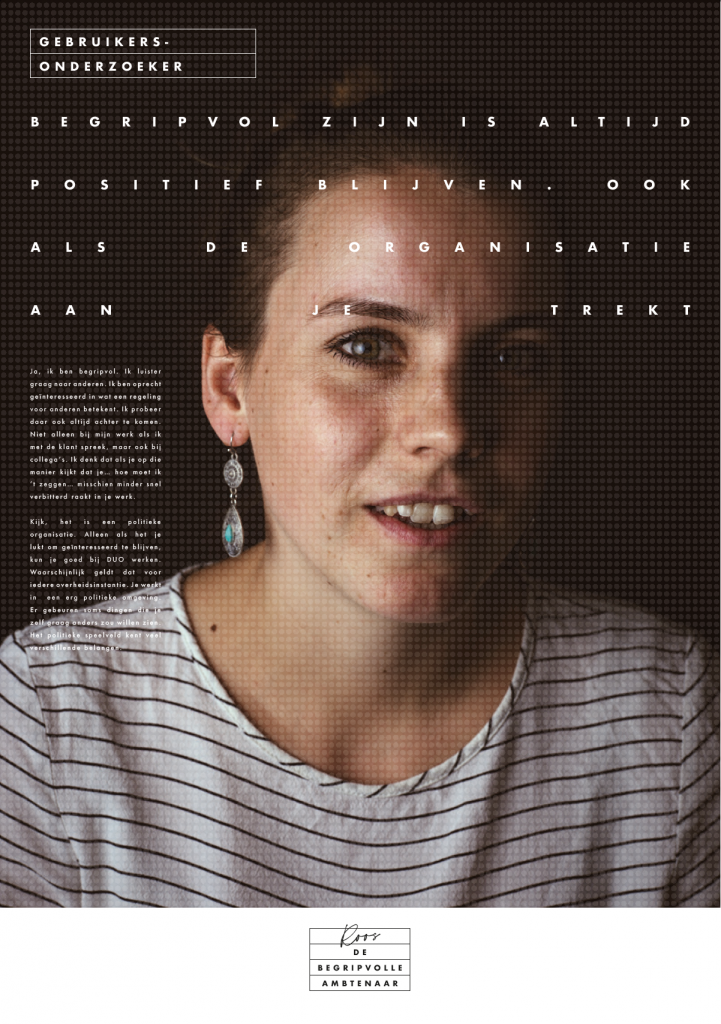

I also know that whistleblowing is not cool because for the past two years, in addition to my work as a user researcher, I have been studying public service problems and blogging openly about them. I did a photo project photographing my colleagues as a compassionate civil servant. You might think, huh, what does that look like? Well, my colleagues wondered that too. When are you a compassionate civil servant actually? And why can’t you be one? We talked about that and at the end I wrote a blog about each portrait.

The reasons why my colleagues are not (or cannot be) compassionate is what I call the dark patterns of government. To understand them, I consulted all kinds of experts, for example Reinier van Zutphen, the National Ombudsman, and Mark Bovens, a member of the Scientific Council for Government Policy. Both have also been guests at the hearings in recent weeks.

Yes, Minister

Last summer, in completion of the study, I wrote several essays on debegripvolleambtenaar.nl about those dark patterns and how we can break them. During the hearings, I heard my essays come alive again. For example, one of the essays is aptly titled ‘We cannot be compassionate civil servants because we are afraid it will become political‘. By the way, the working title I first had was Yes, Minister, after the British TV series of the same name.

In this essay, I talk about the classic hierarchical line that is the default in many government organizations. The minister determines and the implementation executes. In between is a steep ladder of managers and directors, from law to counter. They bear the responsibility, but the substance of implementation lies with the officials in “the operational layer”.

In conversations in Parliament, the Oekaze Kok came up frequently. The Oekaze Kok says that as a simple civil servant you should neither talk to members of parliament nor journalists. It was about “greening”: difficult messages were made a little less difficult up the ladder all the time.

Who was also invited in the hearings: public administration expert Paul ‘t Hart. He wrote a year ago in the Volkskrant that “fear reigns in the civil service towers. Yes, I do recognize that. In fact, there were many colleagues who did not dare to be photographed. Afraid to speak out and afraid of “the consequences.

I found it scary myself to blog about it, so openly on the Internet.

Not a whistleblower, but a gatekeeper

Through my research on government performance, I discovered how to be a compassionate civil servant: by taking your role as gatekeeper seriously. Indeed, at the public counter, policy becomes real. We, the officials who man the front desk, or no, even better, we, officials who make the front desk including all automated counters: we are the gatekeepers. Through us, the citizen meets the government.

Emine Uğur, also a civil servant, articulated this very strongly on Twitter yesterday.

So officials in implementing organizations do bear a responsibility too, not just our bosses. The responsibility how we guard that gate.

Citizen feedback is seeping into our organizations from all sides. We have citizens on the phone every day, they show up on our website, leave messages in our feedback tools, show up on our Facebook channels and submit their concerns and complaints to us. I wrote earlier in this blog: it is my job to research the experience of citizens, and I am certainly not the only one in government with this job. Sure, things can and should be done more often and better, but the officials in the implementation really do listen to the citizens.

Being a gatekeeper means that we also do something with what we hear. That means writing difficult memos, bringing bad news to the surface, giving feedback and putting our foot down when we need to choose the citizen over the boss. That is what I call begin a compassionate civil servant.

But how can we do that if we are not allowed to give feedback to our managers? If they ‘green’ our signals? When we have to listen not to the citizen, but to the boss?

When the Prime Minister calls us whistleblowers while we are just doing our job as gatekeepers?

Government, show yourself

It can be different.

Public administration expert Mark Bovens calls it horizontal accountability in his book The Digital Republic. Where it is usually vertical, the minister does the talking on behalf of everyone, and the implementation thus keeps its mouth shut, horizontal accountability is about the whole ladder being accountable for choices made.

A government that shows itself. All the layers, open and honest and not just the nicely polished bits. Especially the dilemmas, the difficult trade-offs and how government is building a compassionate connection with citizens.

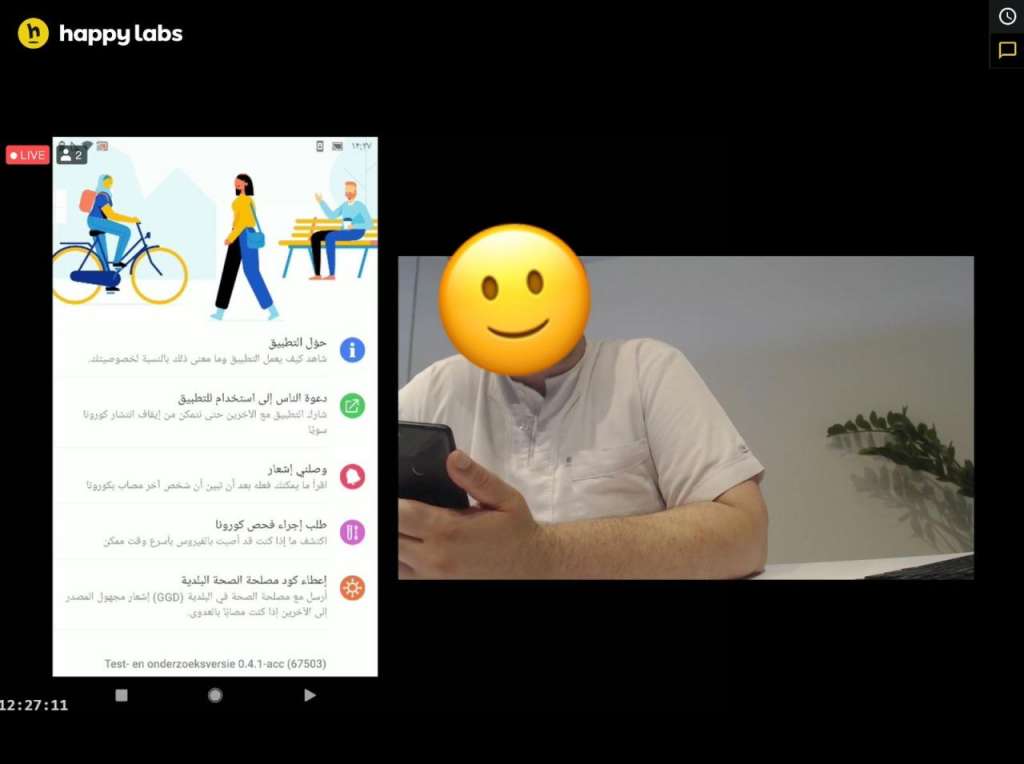

Let me give an example. This summer, I collaborated on the CoronaMelder app. This app was created in openness. I walked along with staff at the local health organizations and observed and interviewed them as they conducted source and contact tracing. After each visit, I wrote a report that was published on Github. With my own name signed to it.

As a result, I took just a little more time than usual to do my reports neatly. I asked a colleague to check in with me to make sure I had substantiated the conclusions. After several weeks, the file grew. You could compare different versions of the app’s design and the research it was based on. Everyone could see how the final app came about, including the crazy ideas that fell through halfway through. In a community, critical citizens and experts thought along. I got difficult questions from them, why I was researching certain things and not others. I also received help to explore further together.

Working this openly can be done at any level. Of course, it goes beyond “posting something on Github,” but it’s the principle that counts. Taiwan’s Digital Minister, Audrey Tang, for example, records her conversations so citizens can read them back because she believes it is important for everyone to be able to see how and by whom she is influenced. How beautiful!

As a society, we want a transparent government that is accountable. A government we can follow and engage with. For that, we need to know how that government operates and we need a level playing field. Government, show yourself so that citizens can come to you. Such an open culture is diametrically opposed to calling internal memos whistleblower signals.

Good example follows, Mr. Rutte: your colleague from Taiwan uses this tool to record and automatically annotate conversations. Taking notes is so old school; there’s an app for that now.