The Department of Civil Service Professionalism at the Ministry of Interior asked if I could list some of my designs from my research on The Compassionate Civil Servant that could help other civil servants reflect. I love doing that, so why not for you too?

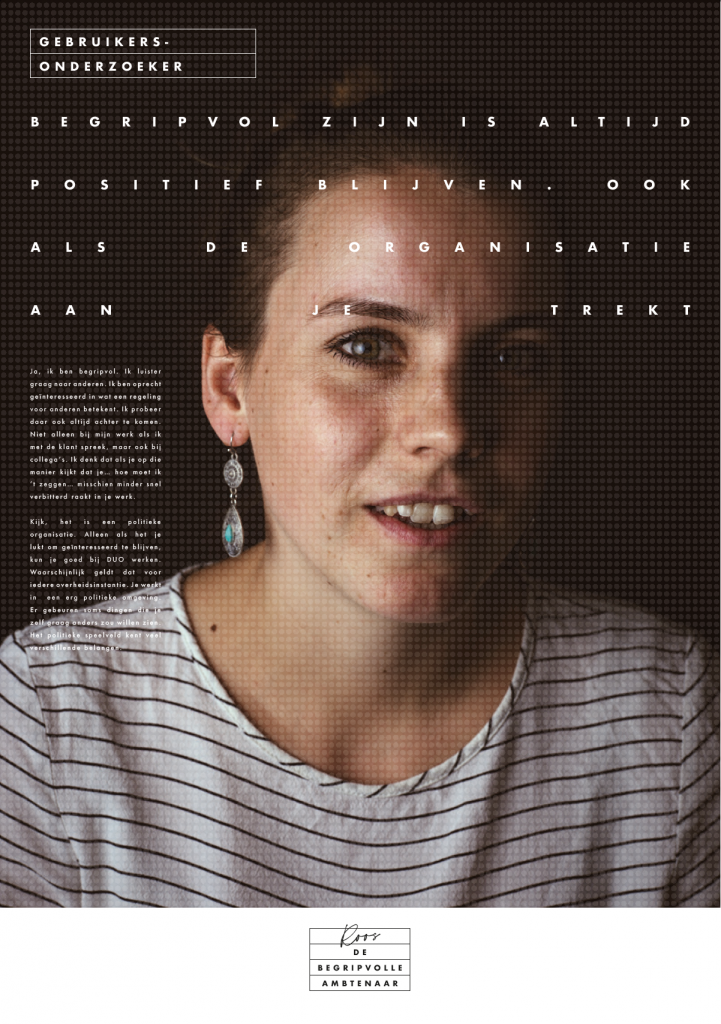

The Compassionate Civil Servant is a self-examination at the Executive Agency of Education (DUO) into what role empathy for citizens plays in our relay from law to counter. I asked my colleagues if I could photograph them as compassionate civil servants. This produced frank conversations. My colleague looked at himself through my camera. And together we looked at all the portraits and what we learned from them. Are we happy with what we see in the mirror? Or do we want it to be different, and how?

The photo interview is not the only reflective experiment I designed. In this blog, a list of other examples, what they are based on (so everyone can get started themselves) and who I was inspired by.

You can read why reflecting is important in my essays on The Compassionate Civil Servant. Or watch in this short film about the study.

Methods and experiments I designed

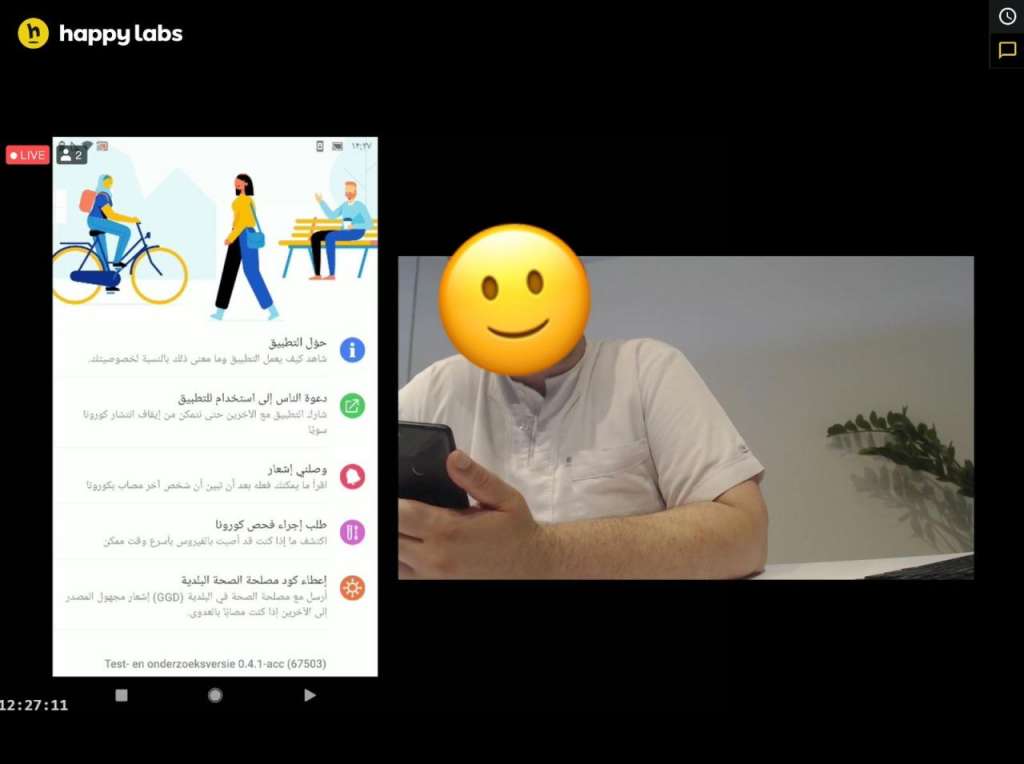

Starting from a central question, I designed experiments to explore sub-questions with participants. This big question was: how can digital government have an understanding connection with citizens.

This method of inquiry is called design research. On this blog, I kept track of the approach and progress. I wrote out all the experiments and findings, and I shared the material so that another organization could easily use it as well. All blogs about the creation of the research are in the archives.

In my designs, reflection plays a major role. I divide the experiments to reflect roughly into 4 categories.

- Relating to the other person. For example, in the rope conversations between students and officials. Or the experiment Stories for Civil Servants in which I played legal texts over a student’s personal story and had colleagues respond to them. Or the role-play the drama triangle I did with a class of students and a few colleagues.

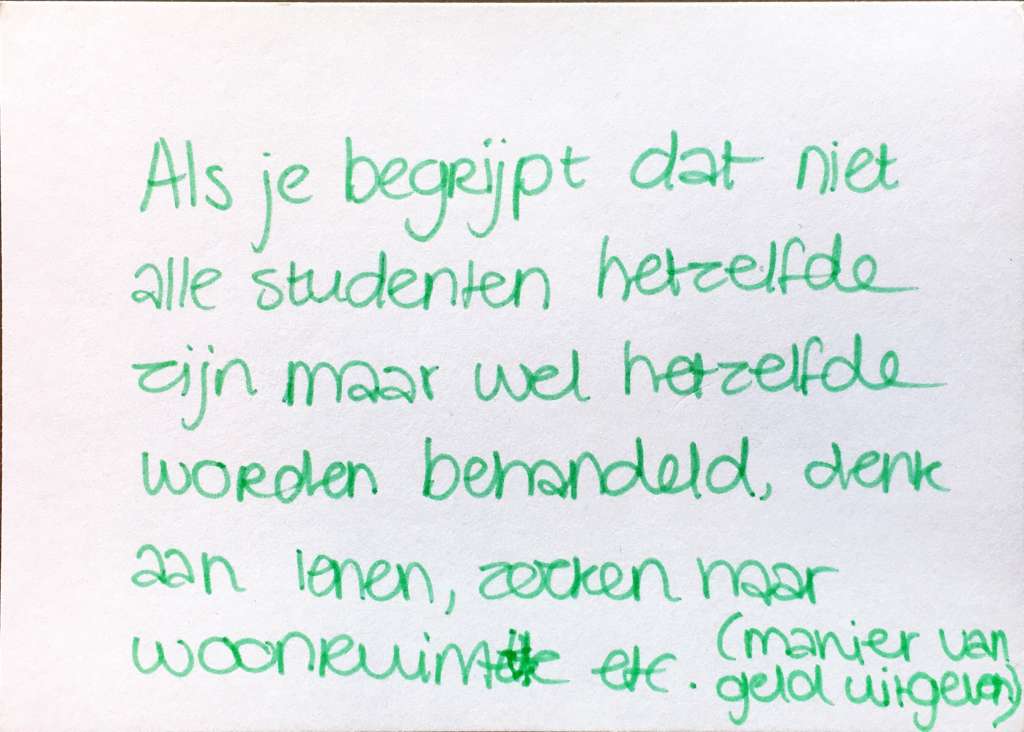

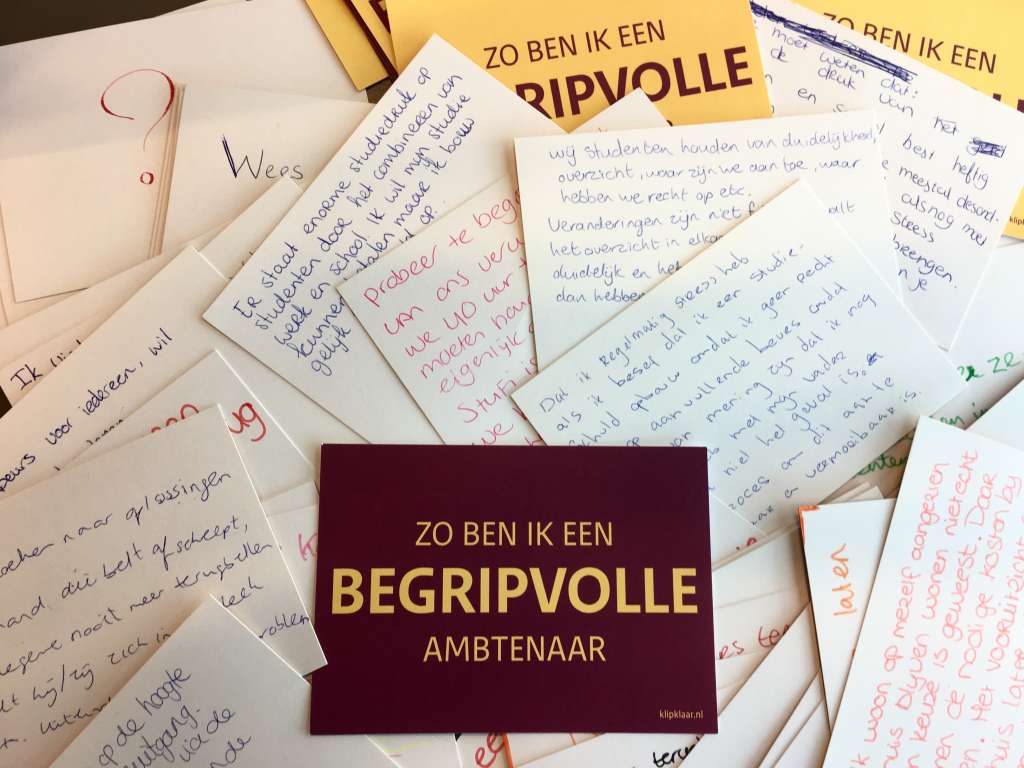

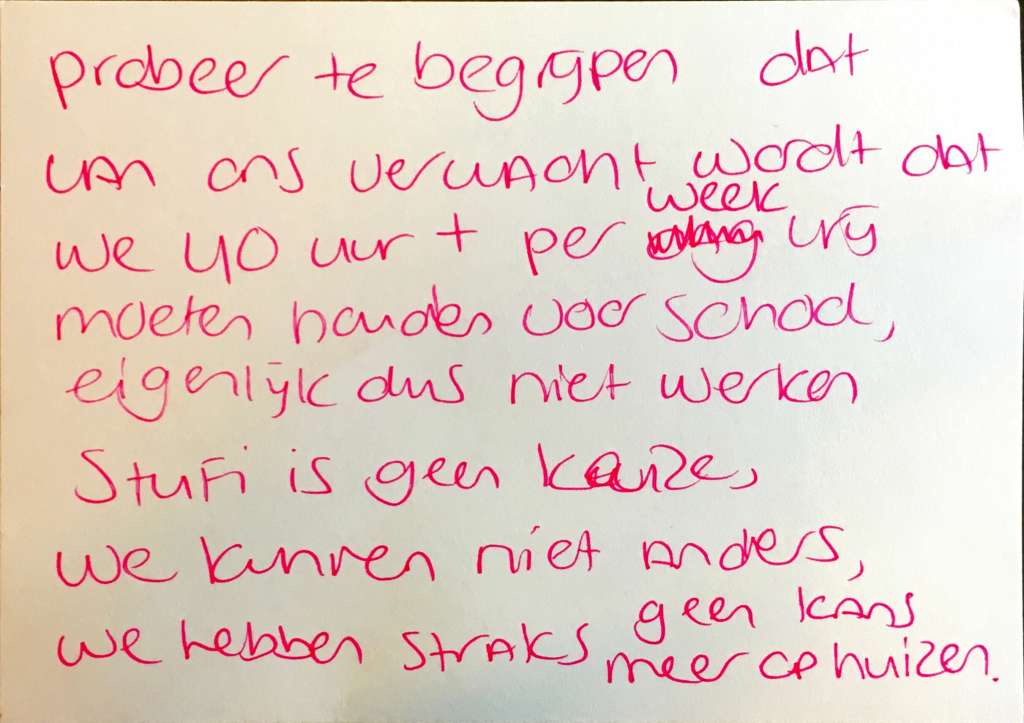

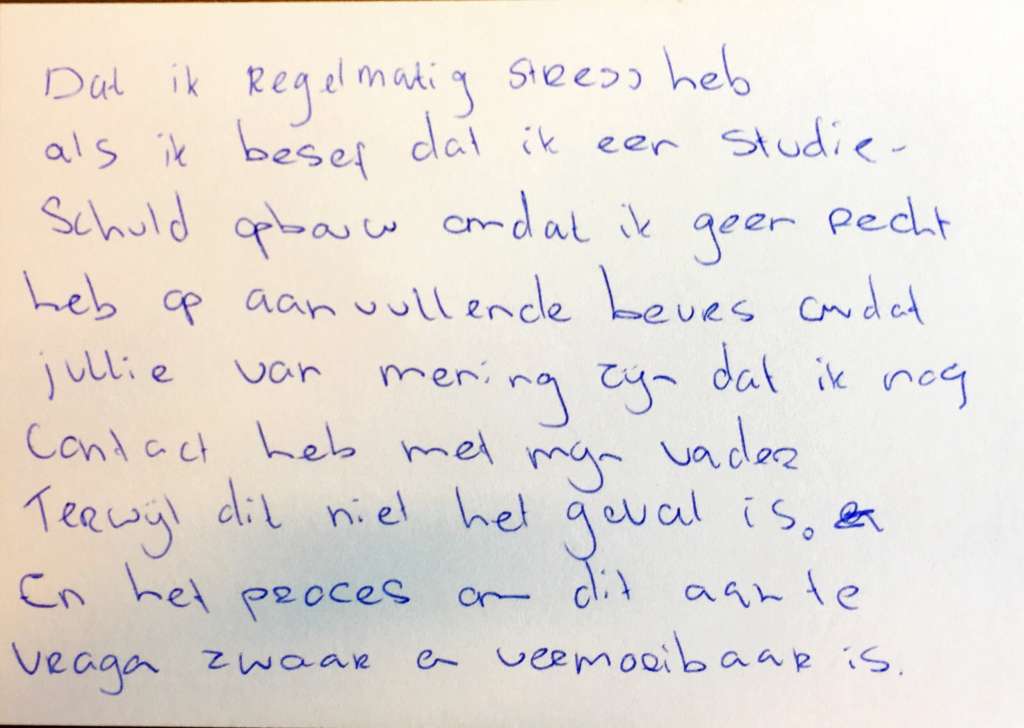

- Listening to how the other person relates to you. For example, working with students and giving them the lead on how they want to explore their relationship with DUO. Or when I myself confronted passersby at the market in Rotterdam. I collected cards from students for colleagues.

- Relating to yourself. That happened in the photo interview, of course. And also in the experiment A Timeline where colleagues reflected on when they could or could not be a compassionate civil servant. I later did this timeline regularly with a group of officials, and it always leads to great conversations.

- Relating yourself to the whole. After each blog I wrote about a compassionate civil servant, colleagues joined the conversation. On the government portal, in the elevator, at the coffee corner. From all the photos together, I made an exhibition. I also organized many semi-public meetings where anyone could exchange stories, often including students. Compassionate civil servant Gabe told (in Dutch) how he experienced all these conversations a year after his photo interview (for my exam :)).

Gabe: “making the implicit explicit.

My inspiration and influences from the work of others

You will find all sources and influences from the study neatly listed. I highlight a few.

Donald Schon’s 1991 book Reflective practitioner, how professionals think in action is the Bible, a tough one admittedly, but the Bible nonetheless. For me, by the way, this blog where I think out loud and can engage in conversation with fellow officials is a way to reflect-in-action as this book describes.

The book Moral Leadership by Alex Brenninkmeijer. Organizations, leaders but also every individual, no matter how small your part in the whole, everyone can and should show moral leadership. In his argument, he falls back on the ingredients from Aristotle’s art of reasoning: logos, pathos and ethos. I wrote about it in the essay ‘Room for our own humanity’.

On the Hidden Design website you will find the strategy and steps I took to set up my design research. The strategy circles and the ways I set up and analyzed an experiment. By the way, they also offer master classes to master this way of design.

I used Jet Gispen’ s Ethics for Designers toolkit to work with colleagues to dissect some of DUO’s service delivery products and reflect on our role.

The work of my classmates Joost van Wijmen and Britt Hoogenboom is intertwined with The Compassionate Civil Servant. Joost uses confrontation and experience in Encounter, his research of the altered body. He makes you feel things and helps you use your body in the process. The timeline I had officials create is a copy paste of his timeline he has seniors create about their changing bodies. Britt explored how she could use images to help people understand each other better. She uses awareness, delay, empathy and connection in her designs. Ideal ingredients for a good reflection. She designed the photo exhibit for me so that it entices officials to do a good deal of their own reflection when visiting. I also met with them every other week on Tuesday nights at a pub to discuss each other’s research. That critical reflection together also helps 🙂

And Astrid Poot. I did not yet know her when I made The Compassionate Civil Servant; she started her research on ethics when I had just finished. But I love how cool she does that. Follow her progress and findings, as she is far from finished. (I was also allowed into her podcast earlier this year where we had a cool conversation about both of our research, fine listening tip – if I may say so myself).

Is reflection allowed to have consequences?

While researching The Compassionate Civil Servant, I stayed with reflection itself, the methods I designed to do so, and what I learned from this first set of reflections. All the spin-offs that arose in the organization (and beyond) were not really under my control. I let that go fairly early on; I was fine with it rising above me, gladly so.

But I sometimes found it difficult, that I can’t really explain well what The Compassionate Civil Servant changed in organizations. How do you measure this? Sometimes I hear snippets of choices made in other organizations because they were inspired by, or read something on this blog.

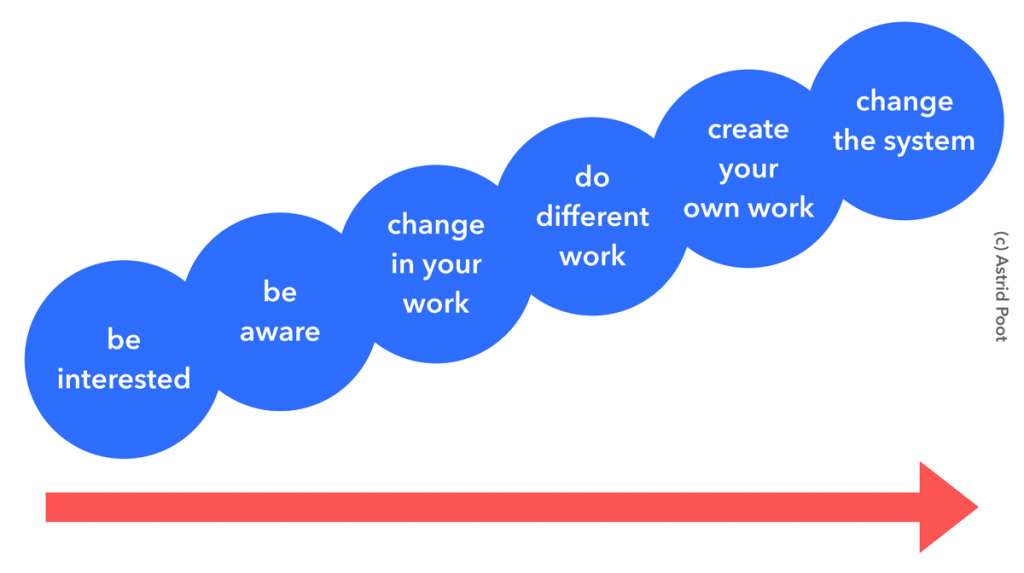

With her research, Astrid is also designing a language to talk about reflection and what changes it leads to. This in turn gives me guidance to better examine and place the fragments I catch. For example, Astrid uses this ladder in her ethics research. Reflection I would put in the first or second bullet.

Reflecting is the beginning. When you start this, anything can happen. That’s exciting, and super. There should be room for this. You can take that space yourself, and if enough people start doing that, things will change.

For example Jean, the analyst in the photo series sighed in his photo interview that he couldn’t do much with empathy as a public servant. After this experience, he set out to shape his analyses from the perspective of the citizen and not just the organization. He wrote a memo to the board on how to give citizens’ doing abilities a concrete role in policy. He was later invited to talk about this at the Academy of Law.

Jean began interested. He helped with the research from the beginning, first in the background later actively participating. He began to change his own approach and set to work to create a new standard so that his analyses properly include the citizen perspective from the beginning.

Of all my colleagues who participated, I can tell that kind of story. Whether they participated in the photo interview and were in full glory on my blog, or in another experiment, or even when they were readers, such a collective reflection does something to you. And it should!

My goal was to initiate a government-wide reflection on our relationship with citizens. And what impact each individual official has on this, wherever you sit in the relay from law to counter.

Whenever I got stuck for a while, I would watch this video.

Can you also do “a compassionate civil servant” with us?

I have been toying with the idea of creating a toolkit of all the experiments. After all, they are all already on this blog, most of them even with instructions and downloads. But reflecting is not plug and play. A tool here, a conversation there. In doing so, I make it too flat, and shortchange my own research.

Reflecting on the relationship between citizen and government, on your role as a civil servant in it, that is something that needs to be done continuously and facilitated. It is a culture change. You can’t do that with just one fun workshop. So as far as I’m concerned, don’t pick one nice experiment from the list, no, pick them all. Because together they have an effect.

Or better yet, design ways to reflect with each other yourself and involve your colleagues. Invite your target audience to that as well. Ha, then it’s about something!

I concluded my essays on the research with three words: open, fair and inclusive. That, as far as I am concerned, is the core of the reflection that needs to be initiated in government. Openess, fairness and inclusive to/ with citizens.