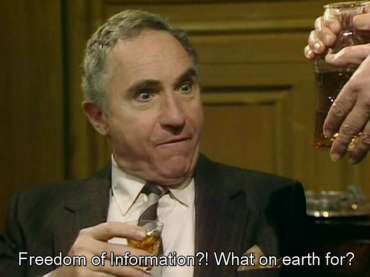

Good resolution for 2023: visit your help desk for a day.

This fall, I visited colleagues at DUO’s Customer Contact Center twice. At the invitation of my colleague Maureen, whom I happened to run into somewhere. I have resolved to do this every two months because really, I am amazed every time at how much you learn from listening in for a few hours.

In this blog what I am learning at these moments and – hopefully – an encouragement for you to also listen in next year at your own contact centre, workplace, help desk, phone unit, ah, whatever you call it in your organization.

9 a.m., report to reception

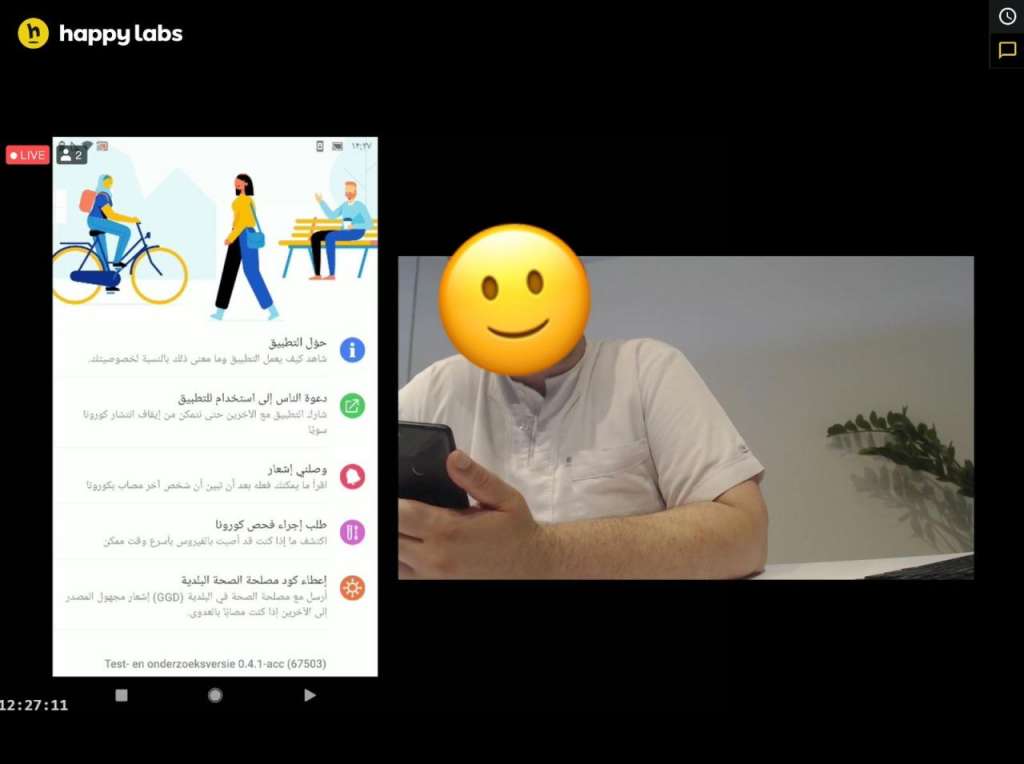

DUO’s contact centre is in another building that I don’t have a pass for. Lisa picks me up, I am joining her today. We get coffee and she starts up all the applications on the computer. When you call a help desk and the employee ‘takes a quick look in the system’… Well, that system turns out to be a bit more elaborate than the image I always had of it.

I get a headset so I can listen in on the conversation. I can’t participate though, I’m on mute. Lisa logs on to the call system and the phone starts flashing.

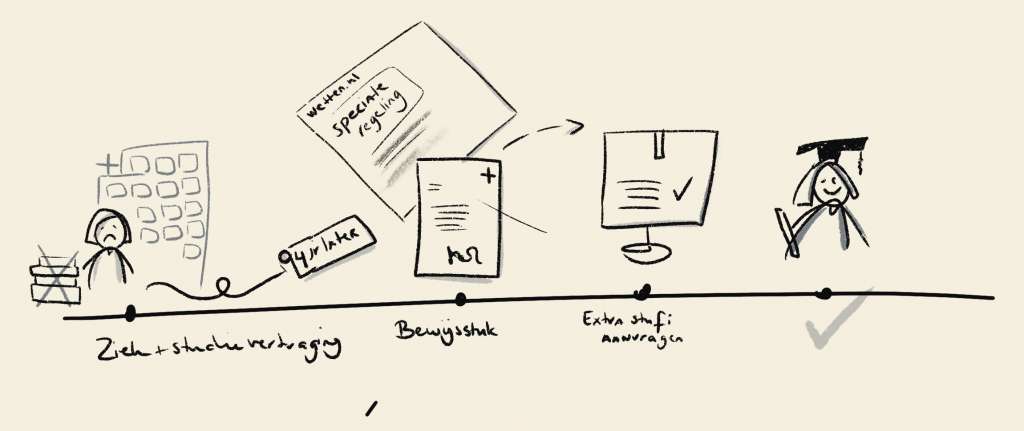

“I had heard that I can get an allowance because of Covid. I am eligible but have not received it yet. I am doing mbo, level 4 and could not do an internship so my studies are taking longer.”

Caller 1

Lisa looks at duo.nl/corona and compares the terms with the caller’s details she has on the screen. Unfortunately, the caller does not meet all the conditions after all. For example, she should have completed her degree by August 2021 but is now only in year 3. The caller is dissapointed, “Isn’t there anything else possible?”

A second caller

“I have a question about my tuition. If I unenroll before February, do I have to pay the whole fee? After all, I want to transfer to another study, I think.”

Caller 2

Lisa does the identity check with the caller so she can see his information as known to DUO. She sees that he has already been enrolled in a few different studies but also that he does not receive a supplemental scholarship. First, the tuition question.

“Would you like to go with me to duo.nl and then click on ‘register and pay for school’? Quitting because you don’t like a study is not a reason to reduce tuition. And if you go on to do another study, you have to keep paying tuition for that as well.”

Lisa

After the conversation, Lisa tells me that she got the idea that he himself didn’t really know what he wanted either. “Based on my answers, he’s going to make his choice.” That seems pretty tricky in how you give advice. Lisa says she regularly talks with colleagues about how to deal with this and give objective advice.

“I also see that you don’t get a supplemental scholarship from us. Did you know this? This is because we don’t have the income of one of your parents.”

Lisa

Lisa explains to the caller what he needs to do to arrange this and then completes the call.

On to caller number 3

“I heard from a friend that you can get an allowance from Corona. Does it apply to me as well?”

Caller 3

This is the second question about corona. Which is crazy, Lisa tells me, because that arrangement was actually very popular last year. Most people entitled to that allowance have already applied for it. While listening in, a few more people call about this arrangement. We see the wait time increasing: there are quite a few callers hanging on the line.

After an hour, Maureen, with whom I paired last time, comes by to have a chat. She says there is a TikTok video going around calling for young people to call about corona. Aha!

But, Lisa and I look at each other, all these young people who called, and didn’t qualify for the corona allowance, we were able to help. As Lisa looked into the system, she could see that some of them had not applied for supplemental scholarships, for example, or were behind on their payments. We were able to address and arrange that directly with them. It was actually very good that they had contact with DUO.

Is such a TikTok movie annoying, because it messes up our schedule, or just a good additional motivation and education for our target audience?

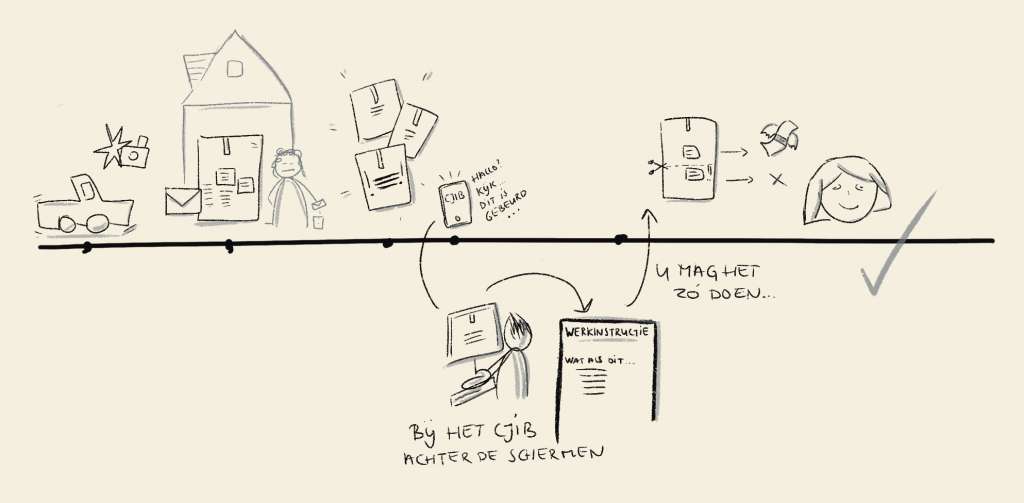

It goes on like this for a while. I see Lisa as she hangs on the line with students clicking through screens, finding messages, taking a quick look in the work instructions to see exactly how things are, and in the meantime kindly explaining how someone can best take care of something, whether it applies to the caller, and giving them extra reminders or something to take care of.

I have worked on some of the applications that I now see in action on Lisa’s screen over the past few years. I occasionally shake my head because it does turn out differently in practice than how we designed it, oops.

Three reasons why listening in is so insightful

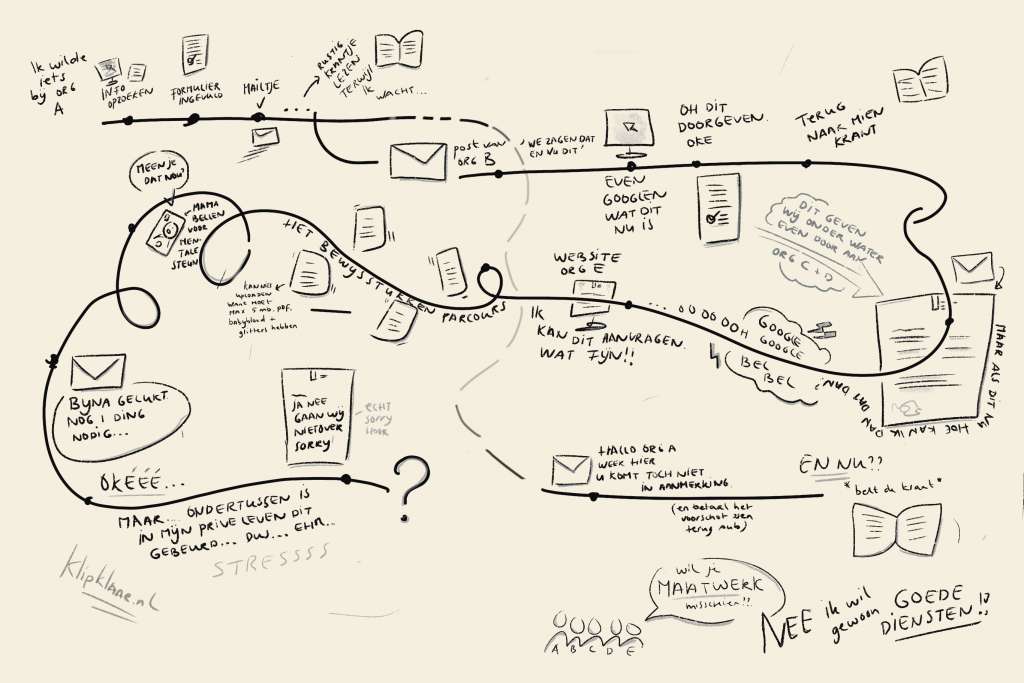

The first reason. You hear what people are calling about, directly with tone, context, and everything to it. On one call, the partner dialed in briefly to hear the explanation as well, on another call there was a mother in the background shouting questions through the conversation, and on yet another call the caller became angry and sad.

Reason 2: You see how employees deal with this. You see everything coming together. It’s very tempting when working on applications to think it’s all about that one thing, but next to Lisa, you see how everything works together (or not). In our organizations, departments are separate, sometimes with different directors even, but on the phone everything comes together.

Third reason: you hear the stories of Lisa and colleagues between calls. Whether situations are more frequent, or incidental. How to deal with difficult questions and where they fix things because they went wrong earlier in the processes. “This is actually something we always look at, because that just doesn’t work well in the process. So then we can give people a little extra reminder.”

Good intention

Therefore, start the new year with the resolution to spend a morning or afternoon in 2023 listening in on the conversations your target audience is having with your organization.

Whoever you are in the organization, the boss, the it-person or someone from legal, it doesn’t matter: listening in is fun and you learn a lot.