For the past few months, I have been following a team in the government that is redesigning services to help people repay their debts to the government. I am looking at what helps and hinders them in making these services human-centered. To find an answer to that question, I must first have a good understanding of what the principles and activities of human-centered design actually mean.

So in a number of blogs in the coming period I will explore these principles. Earlier I wrote about what these principles and activities are. Today we are going to go in depth on the principle: “starting from the whole experience of your users. What is it, how do you do it, and how do you start? Of course, with examples!

What is “the whole user experience”?

I use the ISO standard 9241-210 on human-centered design of interactive systems for definitions. User experience, according to this standard, is the outcome of an interaction a person has with a technological system. This experience is influenced by previous experiences, attitudes and skills of the user. Thus, when we talk about user friendliness (usability), it is more than just making systems easy to use. It is about whether someone can achieve a certain goal effectively, efficiently and to their satisfaction by using a system, service or product.

When you design a service, you make choices: what will the user do and what can the system do? When we look first at what the technology can do, and then leave the rest to the user, we create ineffective services. Instead, the point is to keep as much complexity away from the user as possible. So the tasks for people when interacting with government must, as a whole, be meaningful to them.

Designing from the whole experience therefore means that as a government you take into account the goals people have, the opportunities they have, and short-term (e.g., comfort and enjoyment) and long-term (health and well-being) satisfaction.

In the literature, that is actual Service with a capital letter. That with your service someone can achieve their own goals, and thus create value.

Be-goals and do-goals

So at first glance, user experience seems to be about when someone reads a letter, logs into a portal or uses another system. But it goes beyond that. It’s about whether someone can achieve a goal effectively, efficiently and to their satisfaction.

You have to distinguish between be-goals, do-goals and tasks. No one’s goal is to call CJIB on Tuesday afternoon. That is a task. And that is part of a do-goal, which is to see if, because of an unexpected setback, you can still arrange to pay your debt. And that in turn belongs to a be-goal: that you want to be in control of your own finances and be able to get by every month. A task like “calling CJIB” can support a lot of different do- and be-goals. User experience is as much about these higher goals as it is about tasks.

So what is the whole service?

At DUO, young status holders who are both integrating and studying have to log into two different portals: one for their study loan, which is accruing, and one for their civic integration loan, which is counting down. This is because different departments at DUO implement different legislation: the Student Loan Act from the Ministry of Education and the Integration Act from the Ministry of Justice. DUO is no exception. It often happens that departments are the mirror image of the organizational rake.

Any organization designing a system will create a design whose structure copies the organization’s communication structure.

Conway’s Law, from Platformland by Richard Pope

So to make services that are good for people, you have to start not from your own structure, but from how the user experiences it.

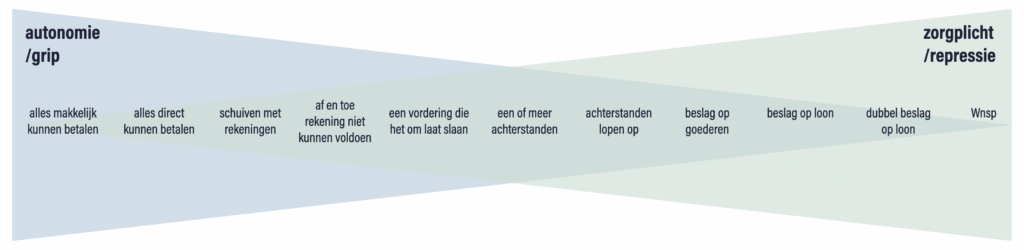

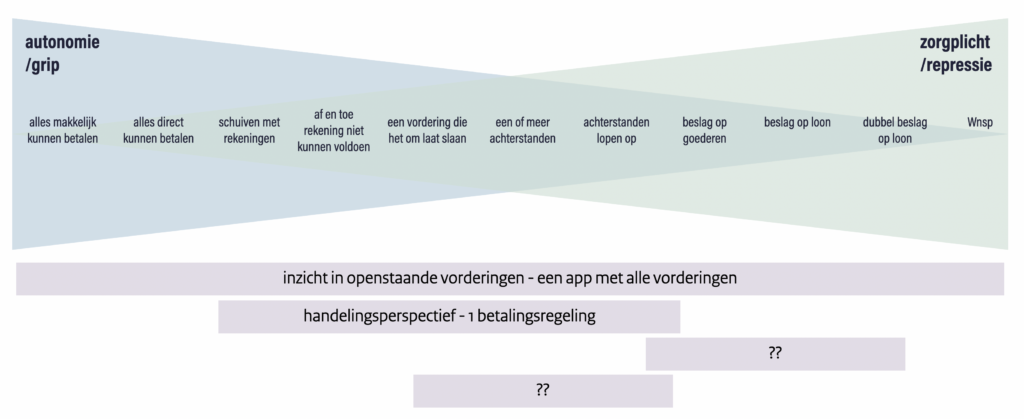

The way the government now collects debt from citizens is the mirror image of how the government itself is set up. The Tax Office collects tax debts, the Benefits Service collects overpayments of benefits, and the UWV offsets debts against the benefits you receive from them. Most customer journeys the government uses assume one claim the government has with someone. While someone can have many claims at the same time with multiple organizations. That’s what you have to design for. And that can include different do and be goals. In the program, we use a spectrum that looks something like this:

Different things are needed at different points on the spectrum. At one end are people who experience a great deal of autonomy, and at the other end are in need of duty of care or repression. The services that are developed, such as a statement of receivables and a payment plan, help people achieve their goals in their situation. By thinking from the whole experience, you can also examine which tasks and goals are not yet supported well enough, and thus come up with new additional services.

I am discovering that thinking from the whole experience of someone in debt, and then designing services for it, is one of the greatest strengths of the program I am following. By eliminating their own organizational logic, they saw how much overlap there can be in debt. And problems around debt easily spill over into other domains, such as health and performance at school or work.

Looking from the whole experience of the citizen makes everyone look very differently at the systems and processes that are in place, at organizational structures and at policies and political assignments. Those are no longer leading, but you can change them all to work from that whole experience.

You don’t start seeing it until you realize it, but when you do, you can’t really go back either.

How do you do this?

How can you work from this principle? The first two activities of human-centered design from the ISO standard provide the perfect starting point:

- Understand and specify the context of use. This context involves both the user and all other parties involved in the problem. Exploratory usage research allows you to identify the actual Service. My blog is full of methods you can use for this. But you can also consider sources of information such as CBS.

- Identify the specific needs of users and other stakeholders. These may include opposing needs that you later need to reconcile in the design. In short, map out the being, doing goals and tasks.

Tips for getting started

- First, take off your organizational blinders. This is the most difficult step. Realize that the structure of your organization does not necessarily reflect the reality outside the office. Shake off Conway’s Law.

- Map out the being and doing goals of your target audience. Use sources that look across domains, such as the Court of Audit or the Ombudsman. Or look at what universities and lectorates write about general topics such as “Poverty” or “Housing.

- Seek out experiential expertise. This may well be on a small scale. Walk along for a day with someone from your target group or with a professional who works a lot with your target group. I recently did that with a bailiff and learned to look at the subject of debt much more broadly than I did before. Invite a few people from your target group to the office for a cup of coffee and swap stories. Listen. It will inspire you to see how broadly you actually need to look at the topic and how much overlap there is with other “files.

- Then actively (and professionally) engage in the first two activities of human-centered design.

- Good luck!

Continue reading

- What is human-centered design? All the principles and activities based on the ISO standard at a glance.

- The being and doing goals come from this article: Hassenzahl, M. (2008, September). User experience (UX) toward an experiential perspective on product quality. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference on l’Interaction Homme-Machine (pp. 11-15).

- Conway’s law and inspiration on making services from the whole experience I got from: Pope, R. (2019). Playbook: government as a platform. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, Massachusetts.