A well-known saying among designers is trust the process. Indeed, since I started working in government 10 years ago, as a designer of (digital) government services for citizens, I have often heard and said that you have to trust the process. In this blog, I tell you why that’s not enough when it comes to government services.

This blog is a summary of my first scientific article “More than the process: exploring themes in Dutch public service practice through embedded research. This article was published at IASDR2023 and you can download it here. Want to follow my research on government services that are good for people? Then subscribe to my newsletter (in Dutch).

About government services

In many Western democratic countries, the state’s job is to provide health care, education, safety and social security. We do this by translating laws and policies into public services. The classic image of a government service is an official with a stamp behind a counter, but today services are increasingly digitized. This has significantly changed the government as an organization and the interaction with government (Bovens & Zouridis, 2002).

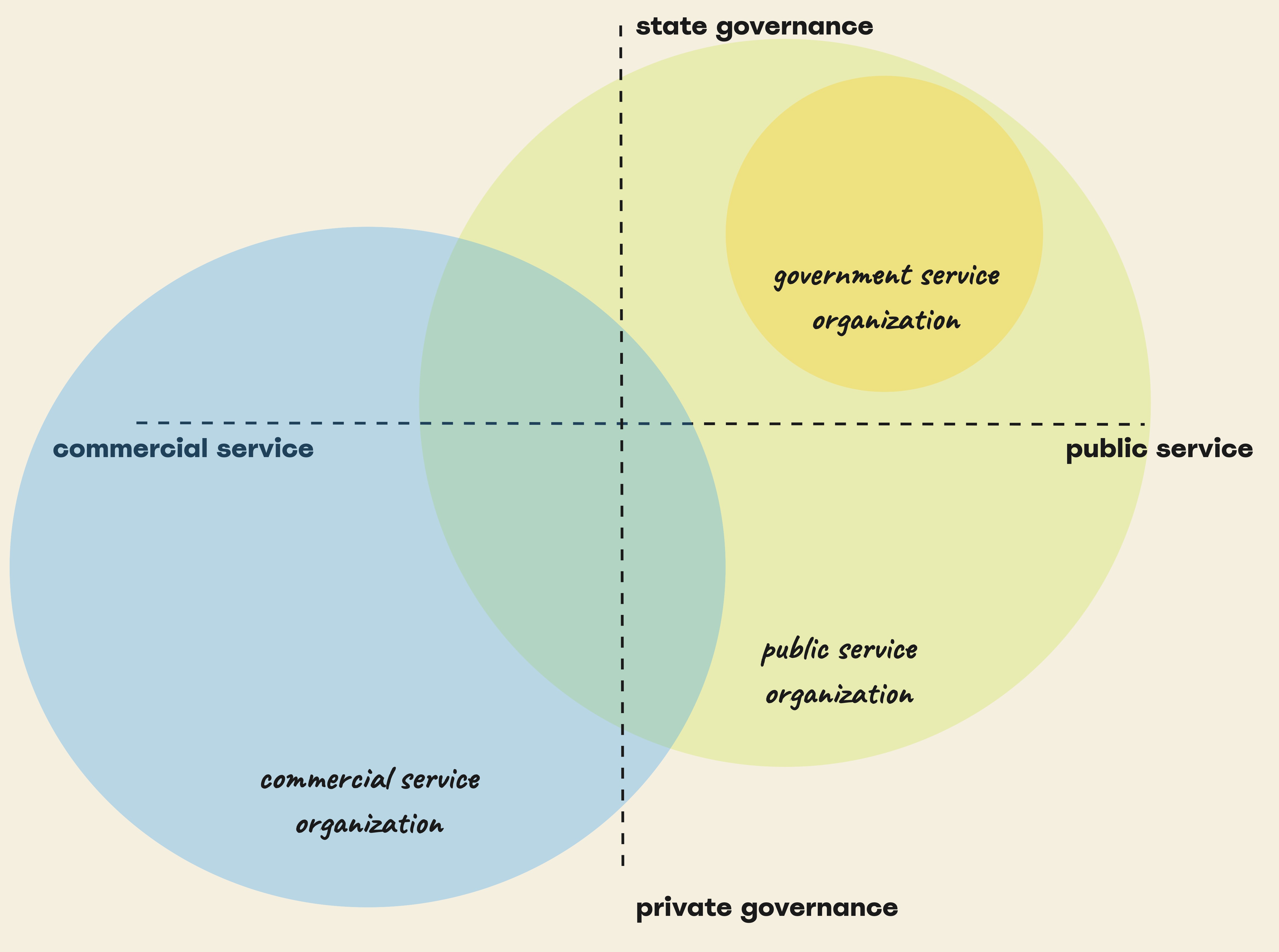

Public service organizations are in in the lead of connecting government (and its laws and policies) with citizens (with their own needs). A public service organization can be 100% government or even completely commercial, or something in between. My research focuses on service organizations that are truly government: government service organizations.

I do my research in the Netherlands. Here we use the word “the implementation” to refer to these organizations, but for a few years now there has been a change. After years of austerity and a few service scandals, the call for more human touch is sounding loudly. This leads to all kinds of change programs to government service organizations within these organizations.

A proven way for delivering human-centered (public) services is to design them human-centered. With the rise of digital services, human-centered design practices have emerged in many government organizations worldwide. But applying this new competence is not without struggle. So write, for example, Bason (2010), Clarke (2020), Downe (2020) and Greenway & Terrett (2018).

What is human-centered design?

Human-centered design is a field that goes back decades. There are now even ISO standards for service excellence (ISO, 2021) and how to design it (ISO, 2019). An important part of this is the service user’s experience. To what extent can users use the service effectively, efficiently and satisfactorily?

There are all kinds of design models for making good services. The common denominator: a combination of divergent and convergent thinking, an iterative way of working and involving users in the design process.

Seven years of blogging in the mix

In 2017, I wrote my first blog about my work to create human-centered services in government. In the archive you will now find a long list of blogs.

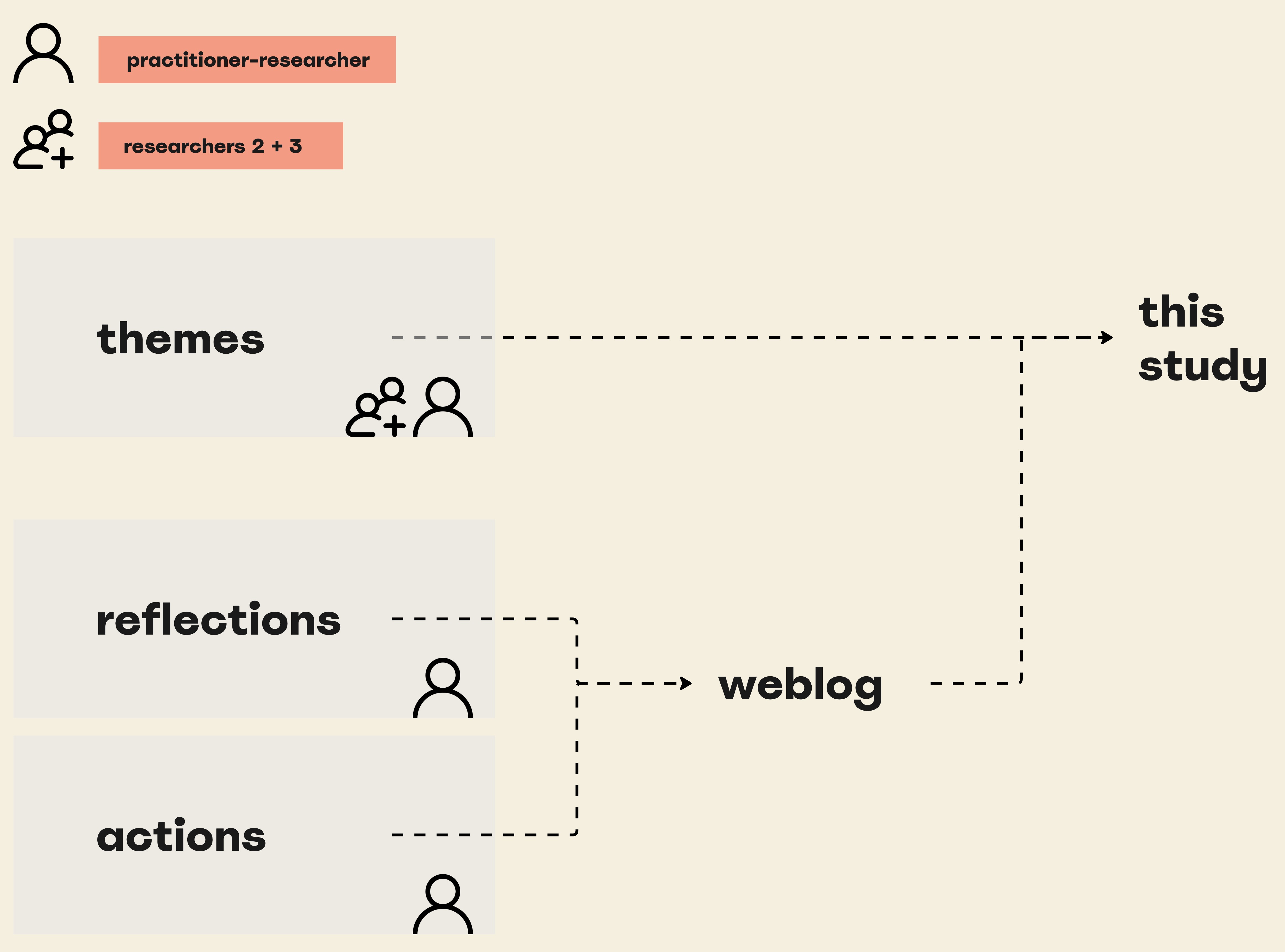

Together with my promoters Maaike Kleinsmann and Jasper van Kuijk, I took a close look at all these blogs. We wondered what we can learn from all these practical experiences. What dynamics do we see that affect how government services are made?

Our research design looked like this schematically:

We divided all the blogs into four projects that followed each other (in part). I will go through them one by one.

Project 1: setting up a UX research practice at DUO

I wrote the first blog about my work at the Executive Agency of Education (DUO) in 2017, and when I left the team in 2021, I created a summary of all 98 blogs up to that point: the structure of research.

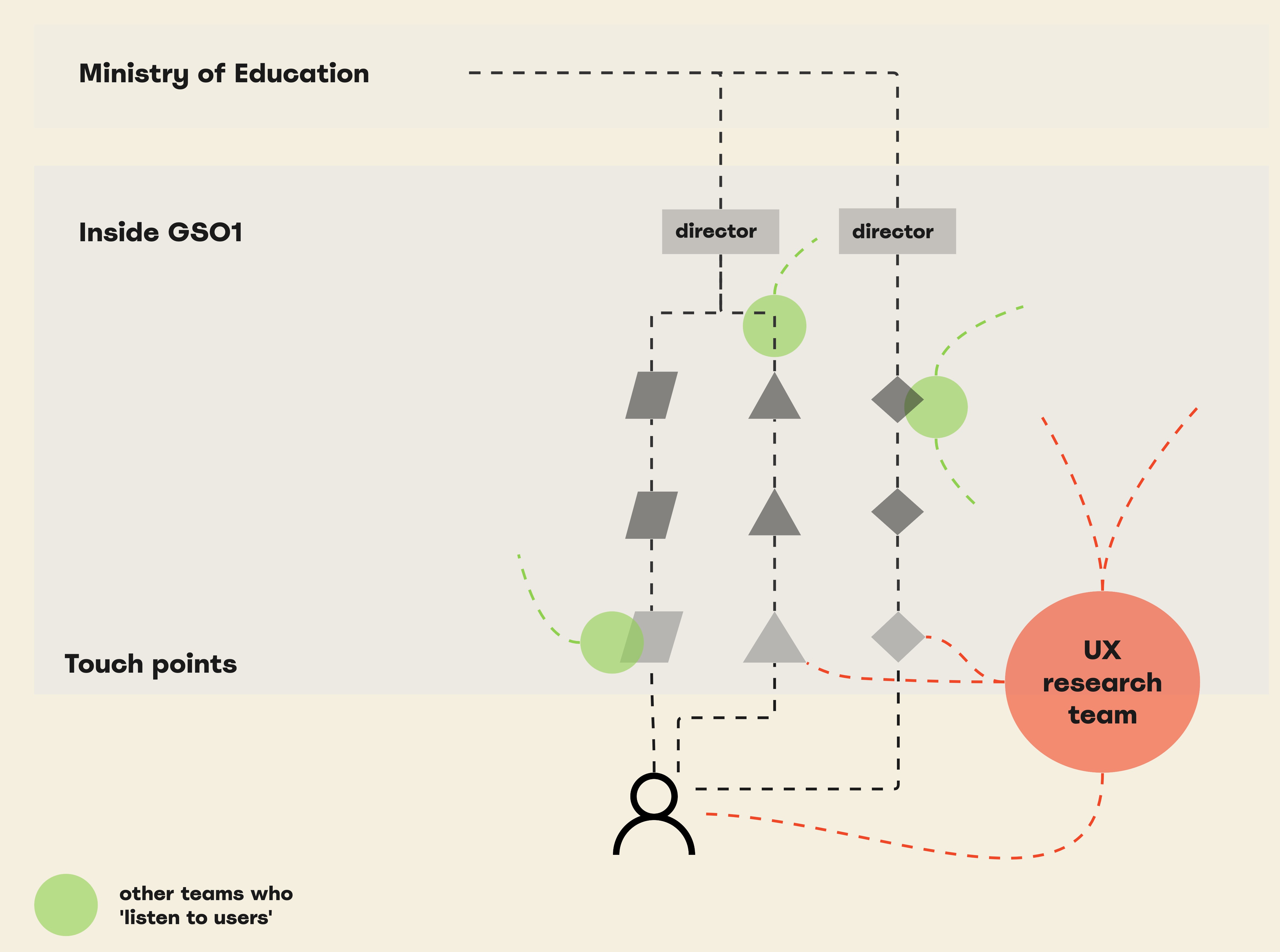

I noticed that the impact of user research remained low. In fact, the process was often finished by the time the user research was done, the website was pretty much done, the system could not be changed, and policy always took precedence.

User research did not fit the way development teams worked. There was no overarching direction on user feedback and no tools such as customer journeys to give development teams guidance. To change this bottom-up was a considerable undertaking, and it was not a priority to better structure the governance of this.

You can see the position of the UX research team in the context of the organization in this drawing:

Delivering services that meet user needs required taking users’ perspectives into account much earlier in the process, I noticed. Thus was born the next project.

Project 2: The compassionate civil servant

This was the research project for my master’s degree on the role of empathy for citizens among digital government creators, also at DUO. I previously shared the results of this research on debegripvolleambtenaar.nl and you can read the work in progress in detail in the archives of this blog (2018 – 2020).

I used photography to reflect with colleagues. This is how it went:

I had four key insights:

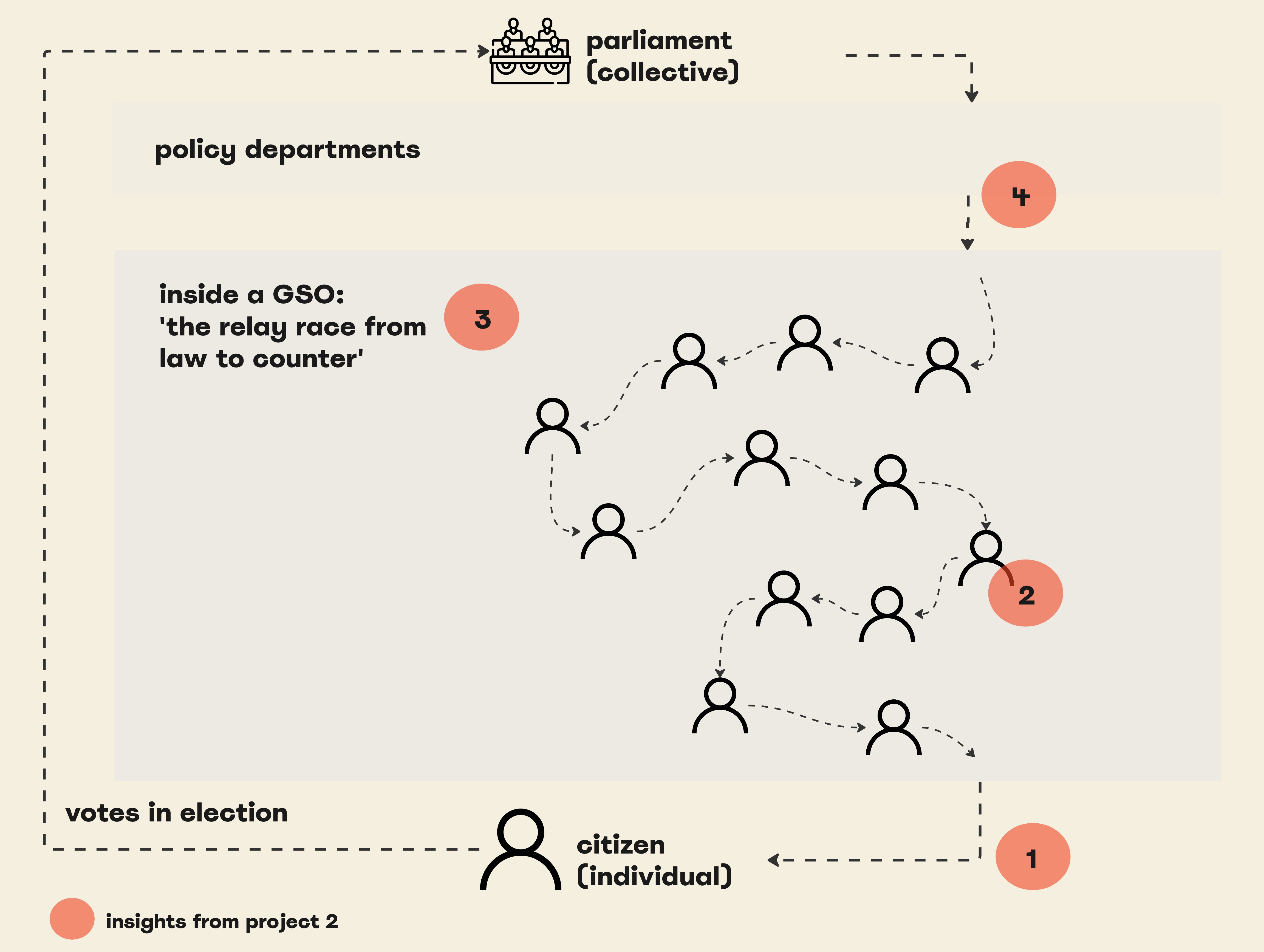

- Participants do not know where citizen responsibility ends and government responsibility begins. As a result, they encounter dilemmas they do not know how to deal with. For example, should a loan for young students be very accessible online or contain hurdles?

- Participants do not experience space for their own humanity. They should be neutral and simply implement the law, but go through all sorts of things that impact them: reorganizations, political changes, unclear communication and their own insecurity. Reflective conversations lag behind as a result.

- Participants do not have an overview of how citizens experience the service and therefore do not know their part in it. Processes and responsibilities are divided. Each one does his piece and passes the relay baton to the next without knowing exactly how it will proceed.

- Participants do not have the skills or feel the freedom to act on feedback from citizens. As a civil servant, you work for the minister and it quickly becomes political, they think. The hierarchy goes from top to bottom: the ministry together with parliament makes the law; the execution executes.

These four insights come into play at different points in the law-to-counter relay, as you can see in this drawing:

Project 3: the CoronaMelder app

For the app, I did part of the user research at the Ministry of Health. You can read back all the blogs via the tag coronamelder.

I chose the corona app as a counter example of how it can be done. The design and development team came together in a special way, using the Covid crisis conditions to engage users at each iteration. This successful way of working was confirmed by the Dutch ICT Review Advisory Board (2022), among others.

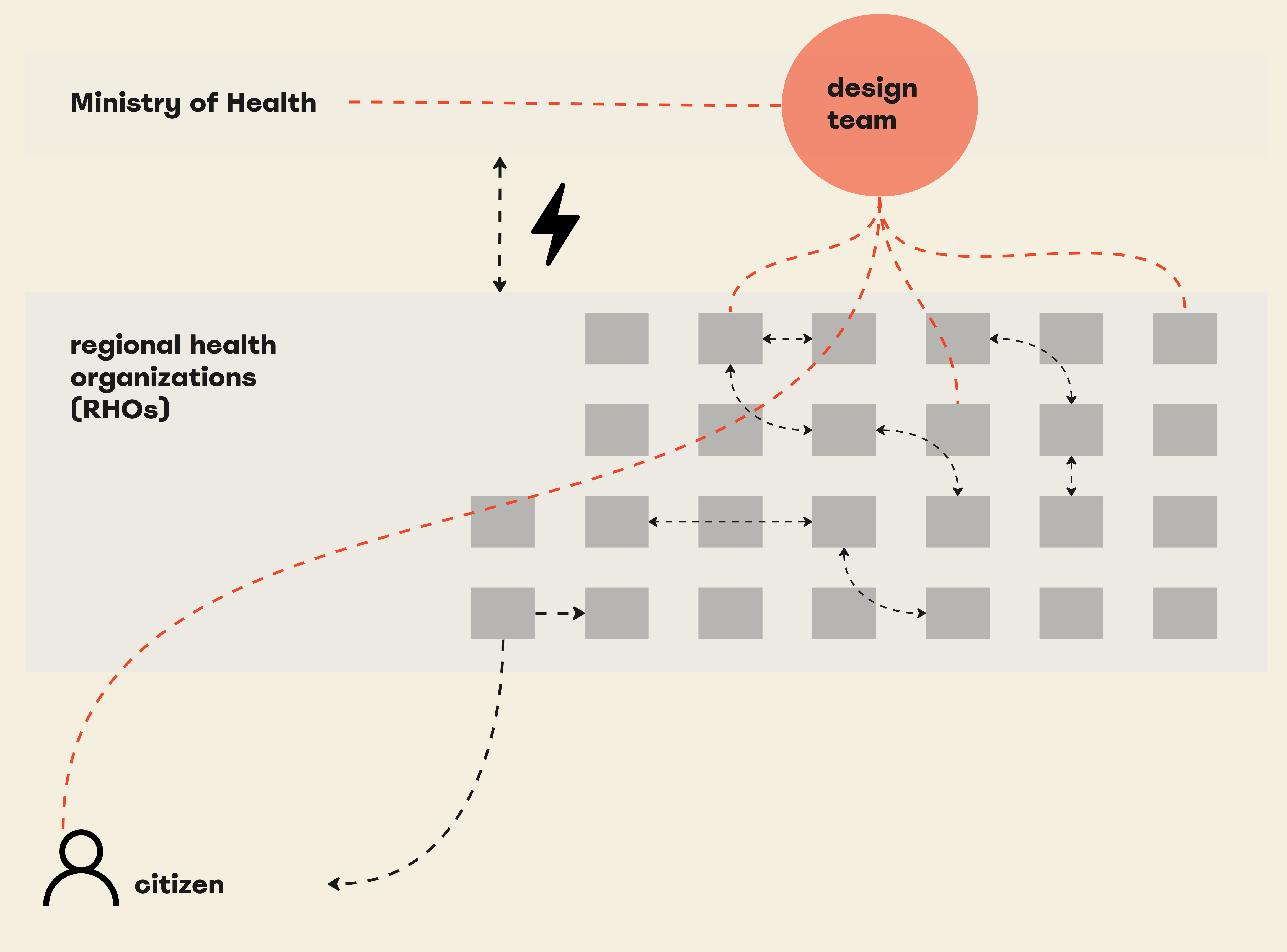

But success shines less when you look at the app not in isolation, but as an interaction point in the entire service, namely source and contact investigation. Responsibilities to combat the coronavirus were divided between the ministry and regional health organizations (RHOs). The dynamics between these organizations led to a less effective app, and this in turn impacted the overall service.

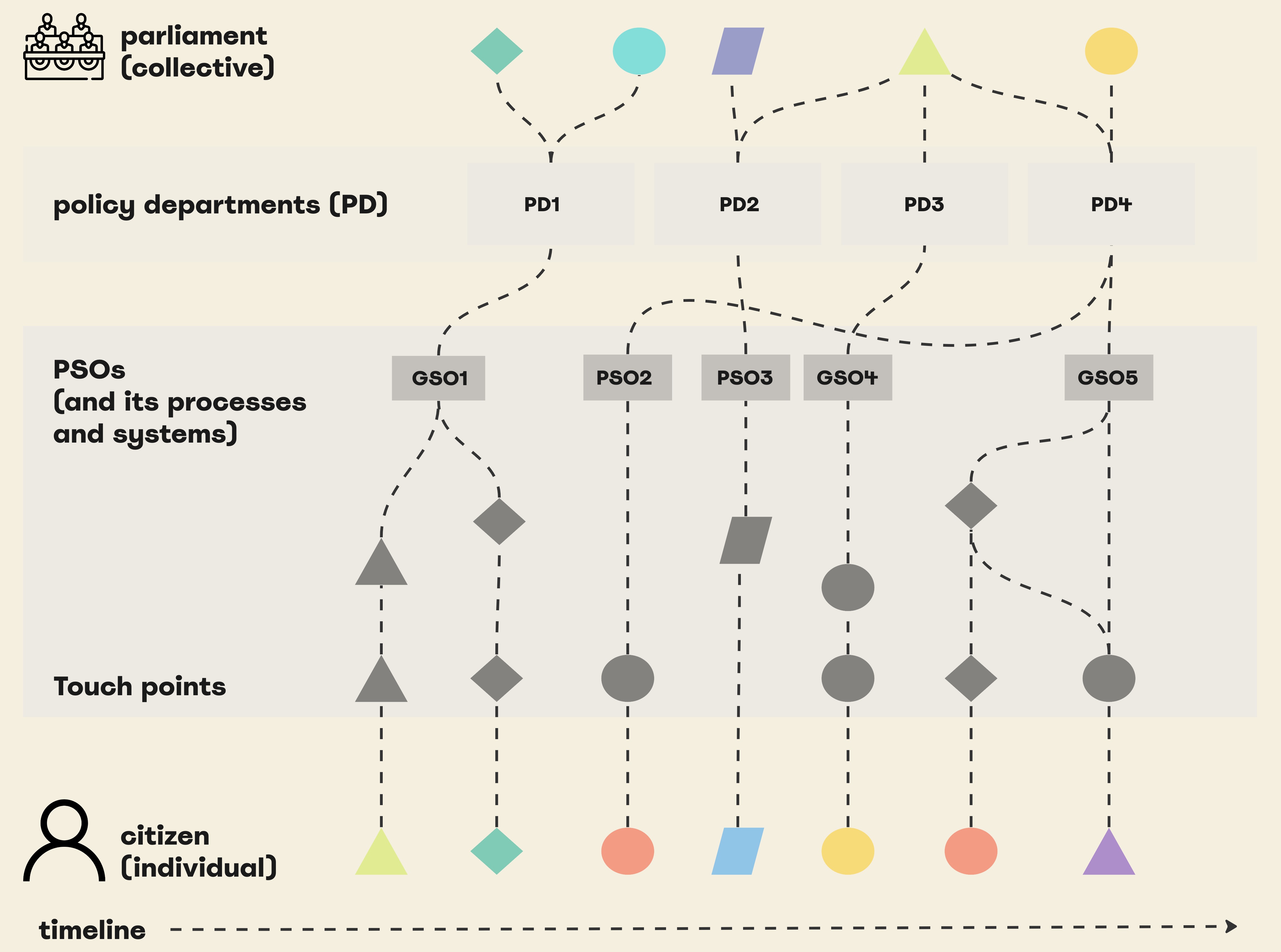

So even though there is a lot of design freedom and users are well involved from the beginning, that does not necessarily make for a successful service. We need more. Apps and services are part of a larger eco-system, as this drawing shows:

Project 4: A month from my own relationship with the government

I explored that larger eco-system by keeping track of my own interactions with the government on a large map for a month and mapped the government’s side of it as well. This project was the starting point for my doctoral research. You can go through the map yourself on this Miro board.

I learned that laws and services for government are always bulk and collective in nature. For citizens, it is always personal. The total of the interaction adds up, as does stress, and citizens soon lose track. After all, you must be a total nerd to want/be able to make such a map :).

The lack of oversight makes it difficult for citizens to manage their relationship with government (Keizer, et al, 2019). Government service organizations do not take this into account because each organization has its own processes, structures and financial flows. There is no overarching responsibility of the entire relationship with the citizen.

The specific dynamics of government services

What can we learn from these government service projects?

- There is tension between collective and individual values. What constitutes public value is defined and discussed by political parties, in public debate and in parliament. Project 2 and 4 show that it is left to the government service organization to translate that collective value into individual experiences, without having the skills or guidelines to do so.

- Government services should be inclusive for all. Not every citizen has the same ability to manage their relationship with government. Commercial organizations also want to be inclusive, but the government has a monopoly. If you don’t manage as a citizen, you have nowhere else to go. Designing for inclusion means involving a wide variety of users in the design process, but as project 1 shows, this is not standard practice. Fortunately, Project 3 shows how this can be done.

- A top-down, hierarchical culture hinders focus on the user. Government organizations operate in a political context (with political reckoning). Read: you work for the minister and less for citizens. Project 1 shows that UX insights were only allowed at the operational level and did not influence strategic decisions of the organization. These dynamics are further explained in project 2. Project 3 shows, because of the team composition and nature of the Covid crisis, that this political culture played a smaller role.

- User feedback competes with policy implementation and ICT changes. Changes around policy and ICT are invariably prioritized higher than citizens’ experience with service delivery. In project 1, you see little room for user feedback in the way the organization works. This is further encouraged by the focus on the legal aspect of policy, as shown in Project 2. Project 3 shows precisely that with the right capabilities and priorities, user feedback can play an essential role in how a team works.

- Government service providers are part of a larger services eco-system. Organizations are part of an interplay of policy departments and other service providers, some of which have even been privatized. In project 4, you see how each organization makes its own translation of the law (or parts of it) into services and takes no responsibility for the impact of it all on citizens. The culture behind this is explained in Project 2. In Project 3, you can see this in the dynamics between the ministry and the RHOs.

Two outsides

Comparing the outcomes of the projects with the literature on human centered service design, I certainly see opportunities for more human touch in government service delivery. But this is easier said than done.

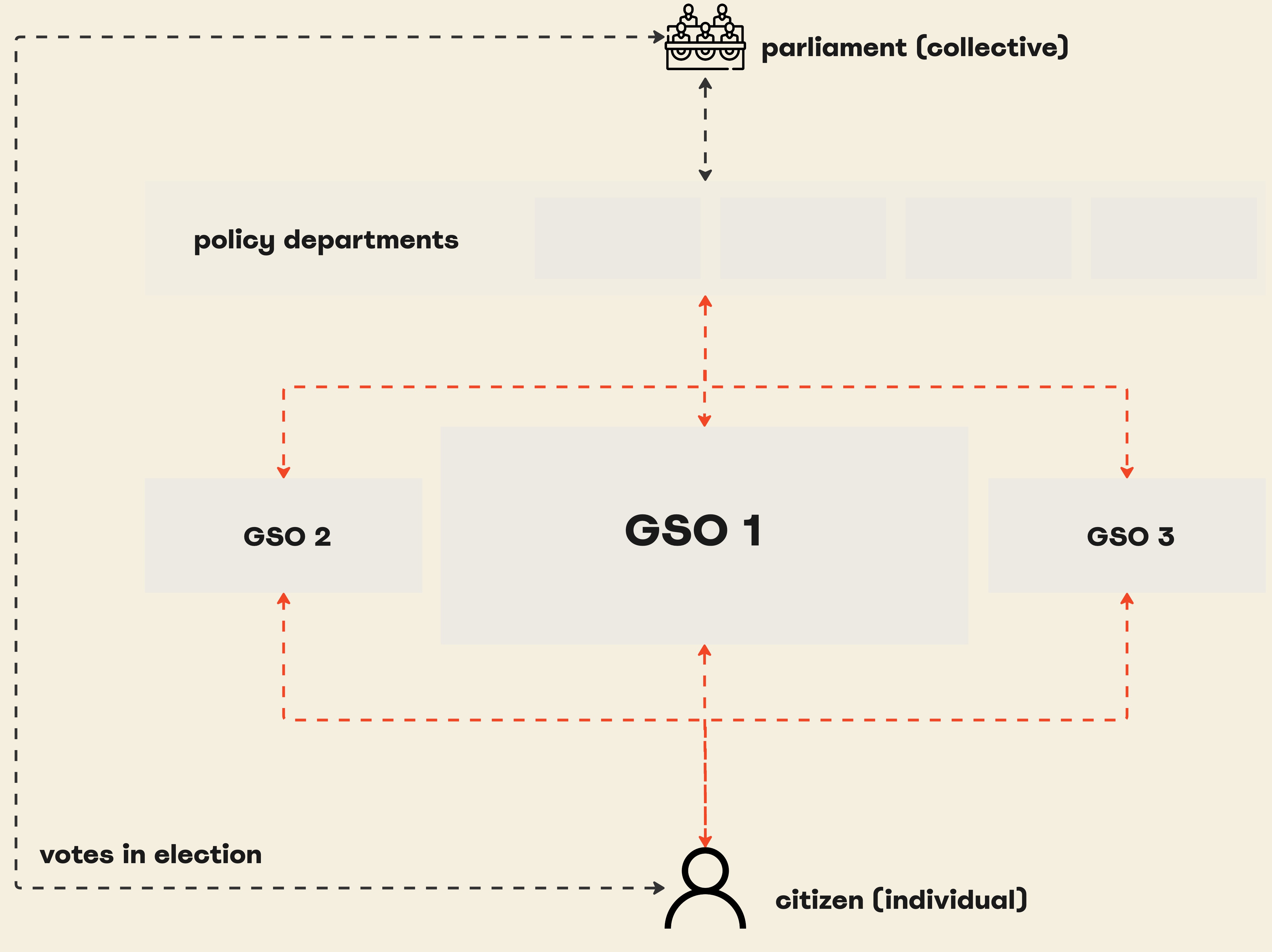

The theory about (making) good service is unruly in the practice of government organizations. For example, the political hierarchy contradicts with the first principle of service excellence (ISO; 2021): “manage the organization from the outside in.”

One would then say that we need a 180-degree turnaround in government, but that does not do justice to the democratic nature of government organizations. The challenge for government service organizations, then, is both to manage the organization from the outside in and to be accountable within the democratic context as well, and thus to listen to two outsides. This is what it looks like:

Conclusion

If we want to create truly human-centered government services, we must embrace human-centered design at the strategic level in organizations (Project 1). An organizational culture that enables this is essential for this (Project 2). But even if the organization has the required capabilities (project 3), this does not mean that the entire service is good for people, since government organizations are part of a service eco-system (project 4).

To make service standards and design processes applicable to the context of government service delivery, we need to adapt them to deal with the specific dynamics of government organizations.

When we do this, it will hopefully enable government service organizations to help citizens achieve their goals in life, even if they need different services from different organizations. Government as a whole must work beyond silos, and begin orchestrating the experience of government services for citizens.

What’s next?

Further developing these standards and design processes is, of course, a nice task for me in my doctoral research.

The first thing I want to do in the coming period is to define some concepts further. I use the term government service organization, but the specifics of this can be explored in more depth. I am going to look at it from different perspectives: from the public administration field, the service literature and from the design field. I envision it as a scale that you can start defining from different dimensions:

This fall I am working on this conceptual framework. Then I will create a research design to research in practice how Dutch national government service organizations learn to improve their services.

If you want to know more about this, read on in these blogs about:

- The open action research approach I use in my research.

- a beginning of defining public value in the context of government services.

- the design field mapped within the government context.

- The multi-disciplinary approach to my research.

References

Bason, C. (2010). Leading public sector innovation (Vol. 10). Bristol: Policy Press.

Bovens, M., & Zouridis, S. (2002). From street-level to system-level bureaucracies: how information and communication technology is transforming administrative discretion and constitutional control. Public administration review, 62(2), 174-184.

Clarke, A. (2020). Digital government units: what are they, and what do they mean for digital era public management renewal? International Public Management Journal, 23(3), 358-379.

Downe, L. (2020). Good Services: How to design services that work. BIS Publishers.

Greenway, A., Terrett, B., Bracken, M., & Loosemore, T. (2018). Digital transformation at scale: Why the strategy is delivery: Why the strategy is delivery, London Publishing Partnership.

Keizer, A. G., Tiemeijer, W., & Bovens, M. (2019). Why knowing what to do is not enough: A realistic perspective on self-reliance (p. 157). Springer Nature.

ISO. (2019). ISO 9421-210 – Ergonomics of human-system interaction – Part 210: Human-centred design for interactive systems. Geneva, Switzerland, International Organization for Standardization.

ISO. (2021). ISO 23592 – Service excellence – Principles and model. Geneva, Switzerland, International Organization for Standardization.

ISO. (2021). ISO 24082 – Service excellence – Designing excellent service to achieve outstanding customer experience. Geneva, Switzerland, International Organization for Standardization.

Adviescollege ICT-toetsing (2022). Evaluatie Ontwikkelproces CoronaMelder. Den Haag, Adviescollege ICT-toetsing.

All 43 references I used in the article can be found here.