My last week at the National Ombudsman’s office is entering. A year ago, I started asking all kinds of new questions that I wanted to learn. The main one: what do you see when you look for a while not through the blinders of government but really from the perspective of the citizen? In this blog, three lessons I learned last year.

Blinkers off means seeing more

When you work in government, you unintentionally have blinders on. This is not on purpose; it happens automatically. It is incredibly difficult not to have the frameworks and agreements you know so well as a civil servant in the back of your mind when you hear other people’s stories.

When you take off the blinders, the starting point is not the regulation or its implementation, but the question: what kind of society do we want to be? What kind of perspective do citizens want? In what context does their life take place? And only then: what place does government have in that story, including my little piece of service provision?

One of my questions a year ago was: how do your experiences with government affect the life you lead and the confidence you have in your future? What causes trust to be lost and how can government restore trust?

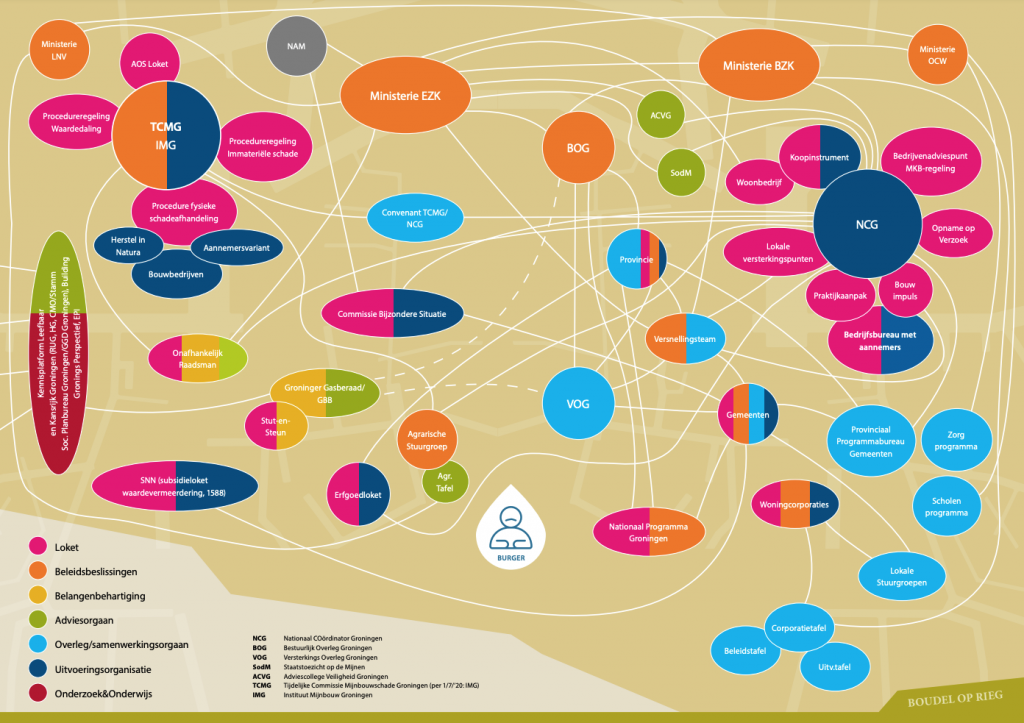

Among other things, I dove into the world of gas extraction: cracks in walls, a debate about what is safe and a lack of perspective and trust in institutions. I sat with Groningers in the garden telling their stories, got in the car with people giving a tour of their village and joined courses for case workers and social workers in the earthquake area.

It was usually not about specific procedures, sometimes it was, but more often it was about confidence in the future. About children growing up without feeling comfortable at home. About not knowing whether you should remodel your house now, or not. About falling behind on maintenance, maybe wanting to move, but can you still get rid of the house? Your life put on hold by a sluggish government. Communities facing not only the effects of gas production, but also shrinkage, an aging population, social problems and high energy prices. But certainly not all doom and gloom either, life goes on. Babies are born, people get new jobs or relationships, dedicate themselves to the neighborhood and meanwhile we live, yes, I live there too, on one of the most beautiful pieces in the sprawling Netherlands.

When you’re making public services, it’s super hard be guided by that whole context. But I found it liberating to take off the blinders and listen to stories freely. Without blinders, my gaze was more open and I saw more.

I dare not say I now have a ready-made answer on how to restore trust. But I saw how to get rid of it, though.

When I was in Valkenburg in March one of the residents left homeless by the floods said: “Maybe naive, but during the floods Rutte, the King, Grapperhaus came here, and ‘the government jumped into the breach,’ they promised. I believed it and thought ‘we’ll deal with it.’ But now there is fuss about who pays the bill and whether the water damage is due to horizontal or vertical water. Meanwhile, no contractor wants to work here yet.”

That’s how you lose confidence.

By going there, you hear the real stories. You see the consequences of a decision that leads to new problems you had not anticipated. You learn this in practice and not at your desk. Listening without blinders means questioning your own assumptions. Not always determining the research question in advance, but going in that direction with an open mind.

I practiced it once at DUO. I asked students to write cards that they thought we should know. Back to the office with those post cards, I got an uneasy feeling. What was I supposed to do with it now? Most of it was about stuff that was out of our hands. Which brings me to my second lesson.

From the citizen’s perspective, government is hassle and chaos

At DUO I was part of the system, at the National Ombudsman I was on the sidelines. You immediately have a better overview because you can survey the entire field at a glance. You also immediately see what a tangle of players and rules it is. So whether you really have a good overview, again, I don’t want to say.

Government is fragmented and cut up into all sorts of loose chunks. Each piece has a defined task or assignment. Within those organizations, all sorts of things have also been cut up and delineated. From an organizational perspective, I understand that, because you have to create structures somewhere and break up big jobs so that the work becomes manageable at the level of teams and employees.

But the citizen’s context is then increasingly difficult to fit in, though. Cash flows including organizations’ own funding run along those cut lines and with them, accountability for the success or failure of the mission. That rich context of the living world of citizens gets lost. Because who can take responsibility for that? Or should I say dare?

Last year, I spoke to representatives of different levels of government. With employees of various implementing agencies working together in chains, with administrators and also with a few ministers. Super fun to hear so many different perspectives, but also sad to see how much speech confusion there is between them. And how much distrust there is between the organizations.

For example, between local governments and the state. Difficult problems are passed back and forth like hot potatoes. That is not a sustainable way of working together. How to do that when major social changes call for a collaborative approach? As with the energy transition where citizens are in big trouble with their energy bills and cannot keep up in the energy transition. Or to give perspective to the generation growing up in debt, with no chance of good housing and steady work? When the climate damage will soon really erupt and be physically felt by most people?

Then we need a government that works well together, listens well and is open to feedback from citizens and each other.

I am really shocked by this.

I didn’t realize it much myself as a government employee. I told a friend of mine who works at the municipality in Groningen the other day. She said once that she could tell from my blogs that I worked at the National level of government. Her response: ‘Gosh, you sure are late to the party’. She and her colleagues had long since figured that out. So that was my blind spot!

I’d rather not be on the sidelines

This lesson I learned about myself. I wanted to take the blinders off and learn more about the citizen’s perspective, but then I lacked insight into the dilemmas of government itself. After making recommendations from research, I wanted to get started. But then again, that wasn’t my job this time. That is not what the Ombudsman is about; that is what the government itself is about. Rightfully so, but too bad for me.

I want to work on those “wicked problems” myself. Wicked problems are problems that are networked, whose context is constantly changing and that involve a variety of competing interests. We can only address these if we start both from the citizen’s perspective and then work from a strong public partnership. We need both.

In recent weeks, for example, I worked with colleagues on a story about the citizen perspective in the energy transition (not yet online). For a workable narrative, that includes the story of the government and not just the citizen. After all, it’s about the interaction between the two.

It’s about how to design schemes from broad societal questions and feedback, make them fit together, how to align policies accordingly, and thus design cyclically with citizens. Basically how we design government together.

I like that the most anyway.