When I saw yet another manel (panel of white men) in a photo on twitter yesterday, a panel that I myself could have been among, I was angry. I angrily texted my girlfriends and then went off to rage row 10km in the canal of Groningen.

You should never blog angry right away, always let a night pass over it but if you’re still angry after that, it’s okay.

So here we go.

In this blog why it is so sad that manels exist and how I myself try to make room on stage that I can share. Because in designing digital government, we need stories and experiences of all kinds, shapes and colors.

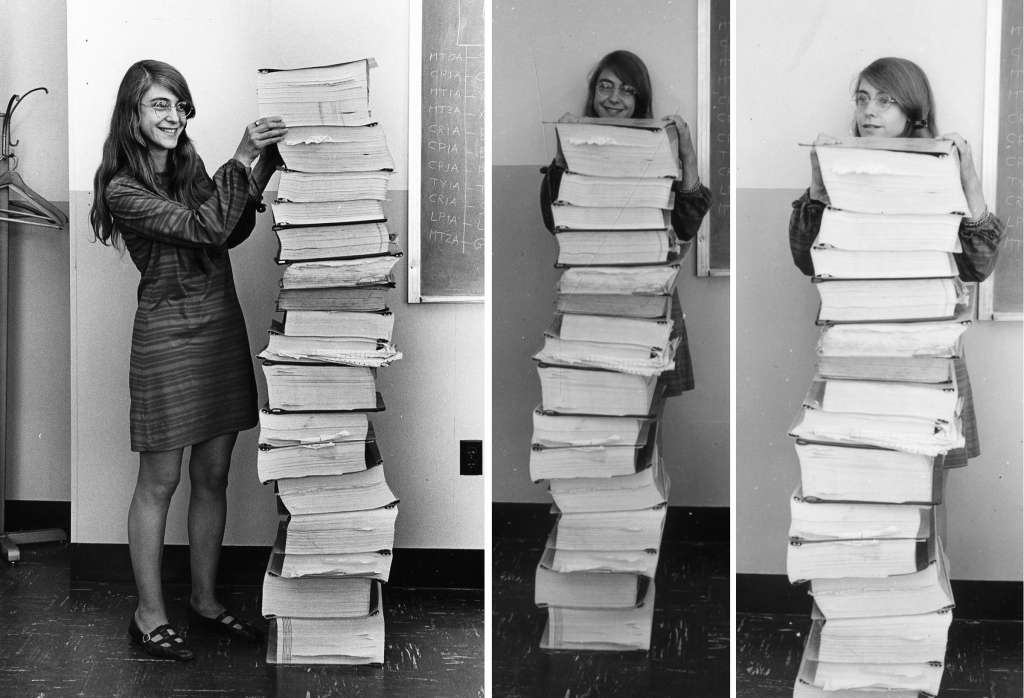

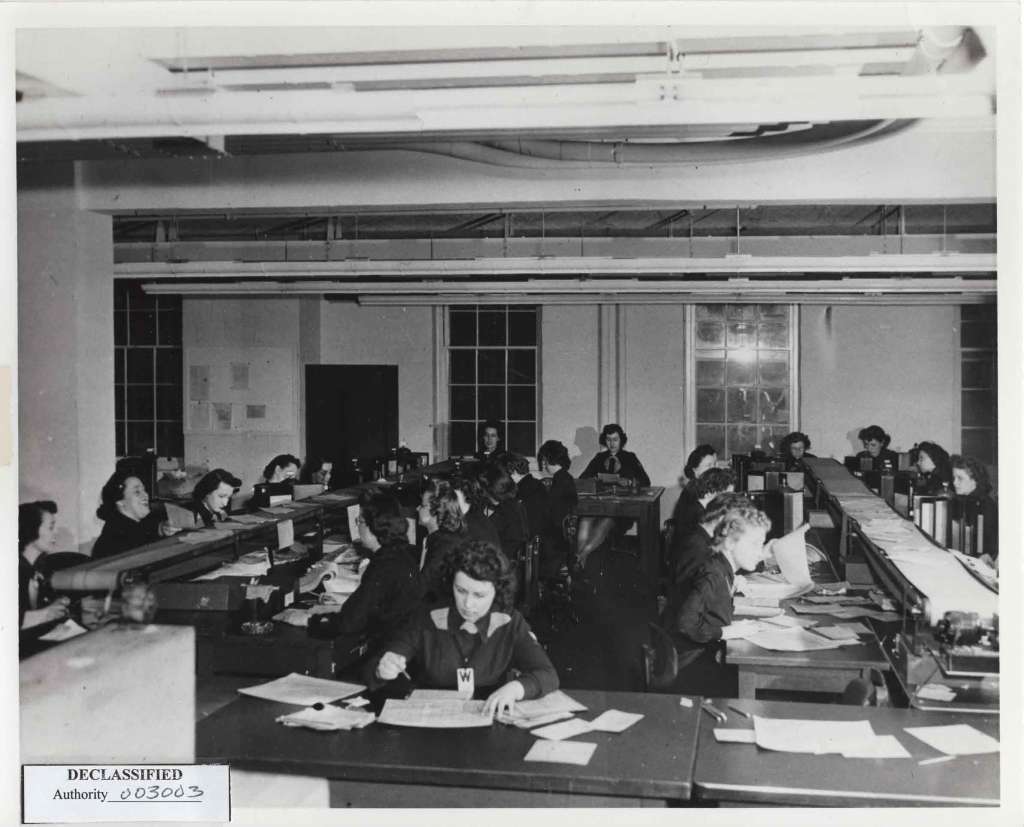

First, about that picture on twitter. It was about this one.

It’s still a man’s world if you don’t invite the rest.

What IBestuur does not realize is that it is very demotivating for (young) women and people of color to see such a picture. This is where issues are discussed, the agenda is set and we get to listen. Don’t tell.

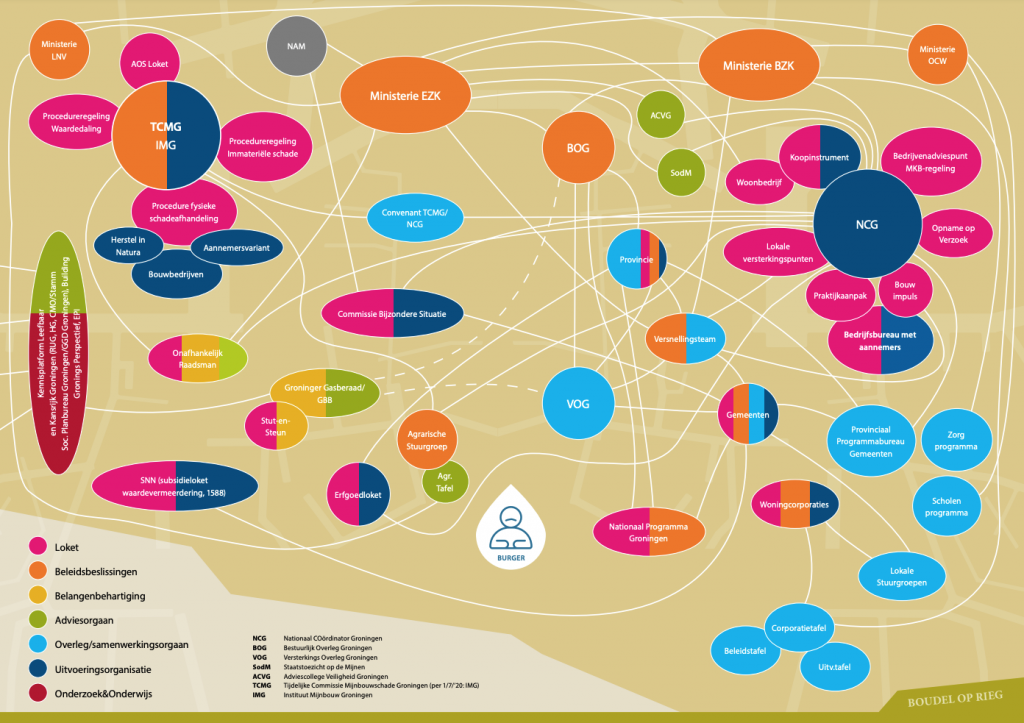

It stings me extra because I was watching the program in the weeks before. The theme of the conference was “digitization and the human dimension. A subject I have only been working on my entire career. Why wasn’t I standing there?

Well of course you don’t say that out loud. But insecurity hit me and the following thoughts ran through me:

- Don’t they know me?

- They don’t think I’m a good speaker?

- Oh god, they think my blog is stupid!

- Should I or my employer have sponsored?

- Should I have just boldly invited myself?

- But if I do that, won’t they think I’m way too cunning?

And so I did nothing.

And didn’t go there either. Because even though the theme was “human dimension,” the program looked mostly classically IT. Too bad, because if I did go there I might have met nice people, shared knowledge and learned new things. And there had been one more woman anyway, if only in the audience.

The first time I thought ‘I want to tell something too’.

It was years ago, 2017. With some colleagues from DUO, I was in London at a Government Digital Service conference. Lou Downe talked about service design and I thought they were great. In casual sports pants, they told how to make government services that are good for people. With humor, style and in a way that I thought ‘I can make such services too’.

During the break, I started this blog. I wanted to write down and preserve what I learned as a junior researching civil servant. Maybe others had some use for it as well?

Through this writing, I got to know Karin den Bouwmeester. She organized meet-ups for user researchers that I attended more and more often. In small rooms we told each other how we did our work, for example about usability research together with Aegon. Later, at UX insight, I got to do my first talk on a stage (with lights!). I gave a ten-minute presentation on the Integration law and the research I had done for it. I had memorized the entire ten minutes and despite the fact that I was throwing up on the toilet from stress just before, it went pretty well.

A few years later, I started a new course where I had to talk to experts. In online articles, I came across Marije van den Berg. A world opened up to me: this is how our democracy could be if we organize it together with citizens. With a big bunch of flowers, trembling knees and a friend for mental support, I walked through Leiden. Needless to say, it was a super fun conversation and we have since made a podcast episode together and she is on my speed dial for questions about government, life and happiness in general.

From Marije, I also learned why sharing is such an important part of your work. She explained to me, withthis blog by Harold Jarche, that people who research a lot, know how to make sense out of it and then share it, are very valuable. These are fine people to follow, to work with and we desperately need them to tell the good stories. That’s how I wanted to start blogging, too.

After Marije, there were more conversations like that. For example, with Marlies van Eck. I had used her doctoral research on legal protection and chain automation as an important foundation for my research on empathy in digital government. I even had a whole blog dedicated to her (hahaha, it is the ultimate fan blog – I am not ashamed). When I finally found the courage to send her an email a year and a half later, it went like lightning. She asked me to give a lecture together at the NSOB and to help in a project to research algorithms.

Where is the stair step?

When I started blogging and sharing, I didn’t have so many examples of how to do this. I didn’t know any other civil servants who blogged. Who shared their sense-making.

On the big stages were, yes, actually like yesterday, white men in suits. I didn’t know the rules of their game. I didn’t have a suit either. I don’t recognize myself in that world at all. I had no idea where the steps for such a stage were.

So I happily tapped away on my blog.

Sometimes after posting a blog I would get stressed about the reactions. Colleagues who thought it lacked integrity. Am I doing it right? Who can I imitate? I once heard in a podcast of Haagse Zaken that you are not supposed to do this kind of thing at all as a civil servant. That the “Oekaze Kok” says you can’t talk to journalists or chamber members. Well, yes, I didn’t. Not directly. They probably didn’t read my blog.

Again, why did I want to tell things when it stressed me out so much?

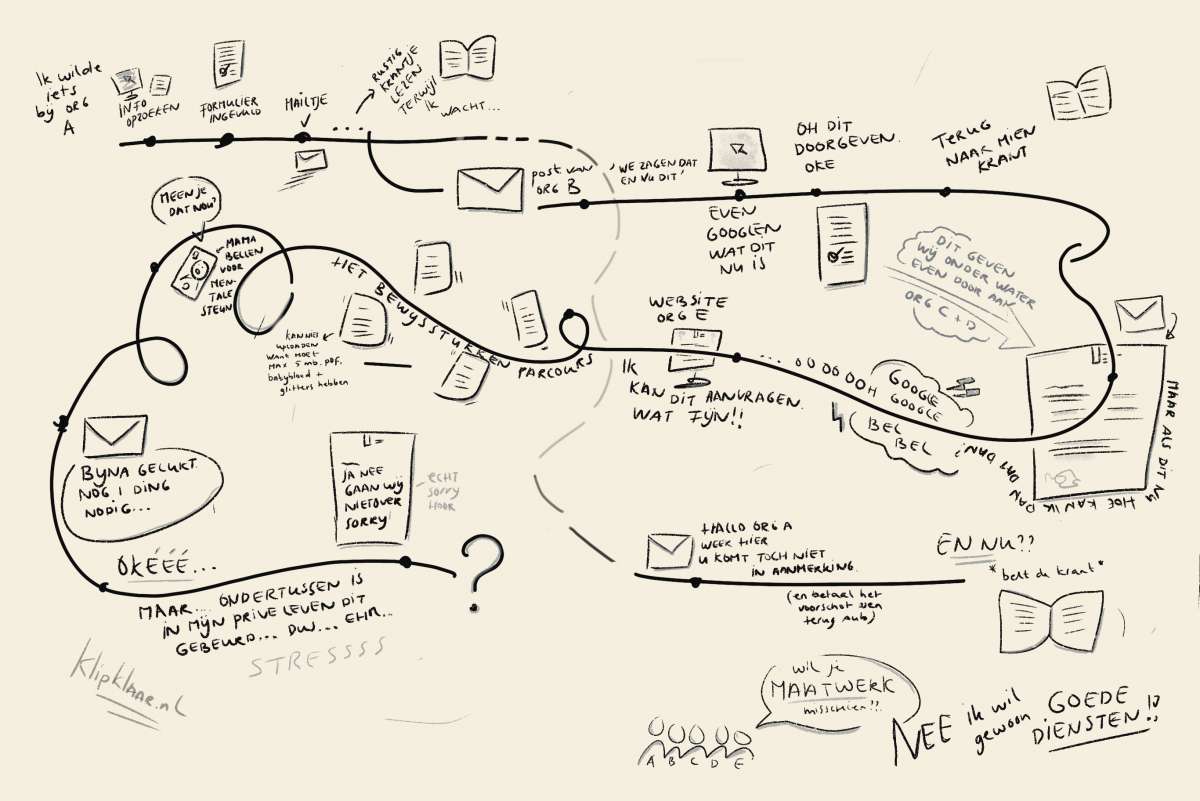

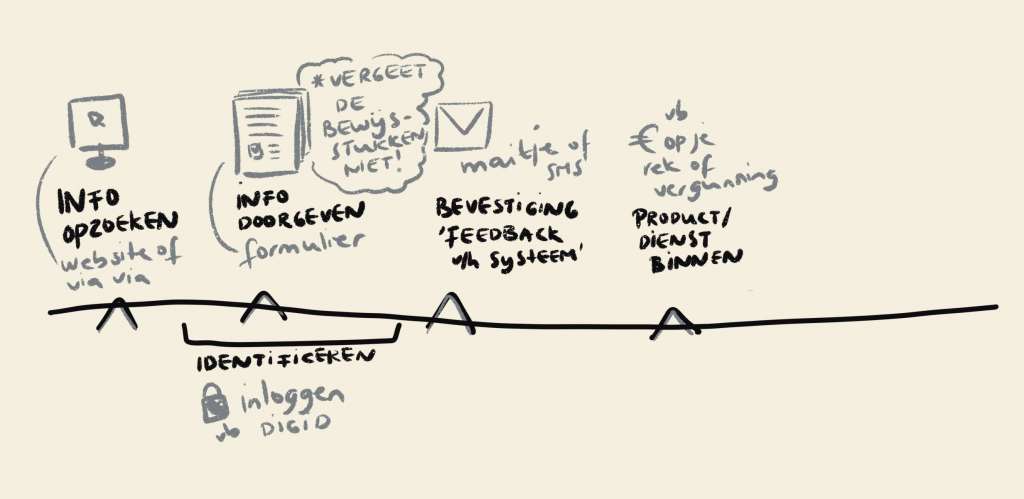

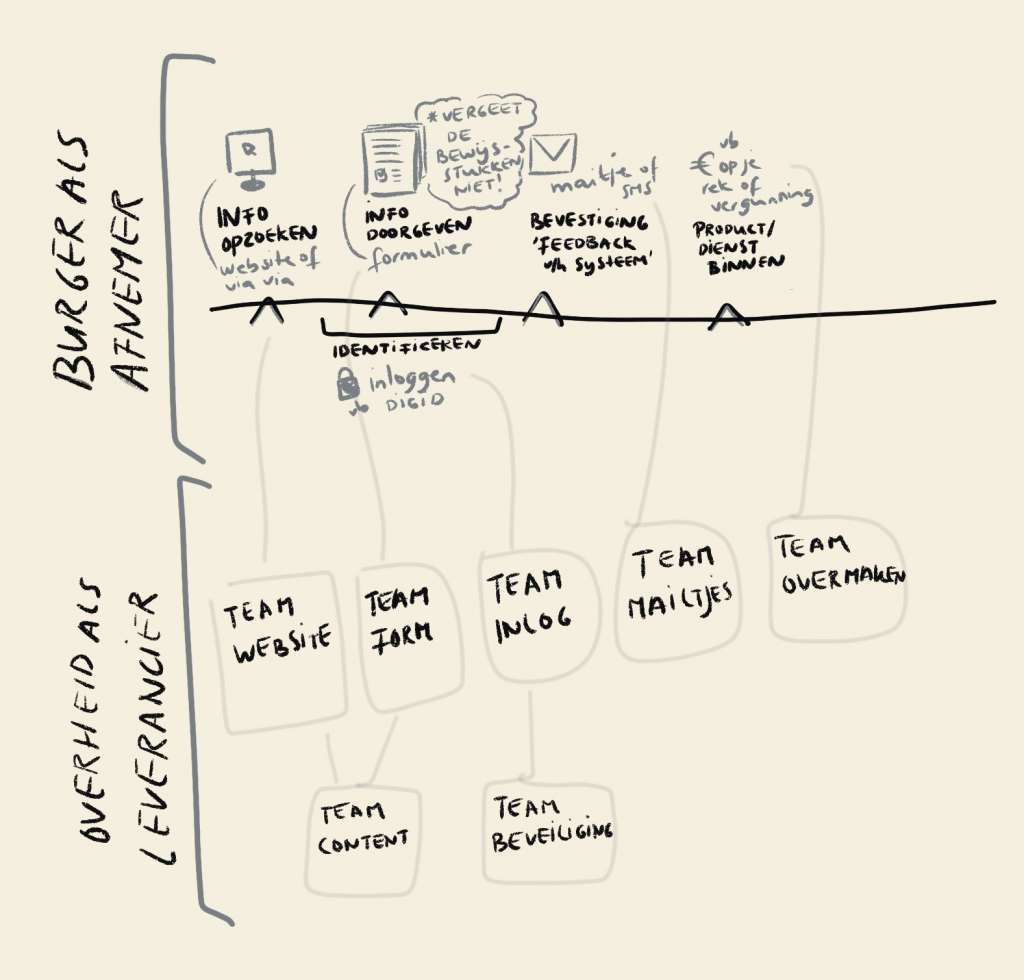

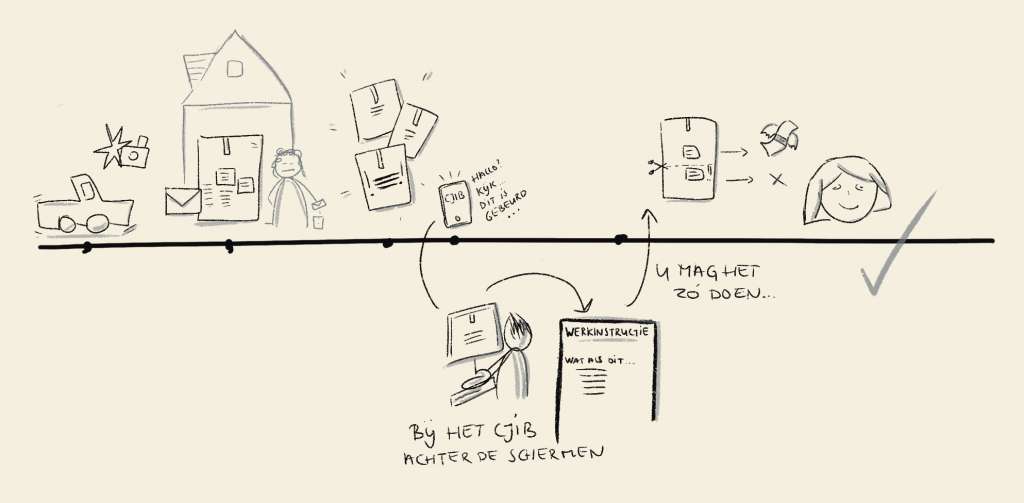

For those unfamiliar with my research The Compassionate Civil Servant: I researched with my colleagues at DUO what place understanding citizens should have when we make digital government. How are we compassionate civil servants and what does this mean? Where in the law-to-counter relay should this actually have a place?

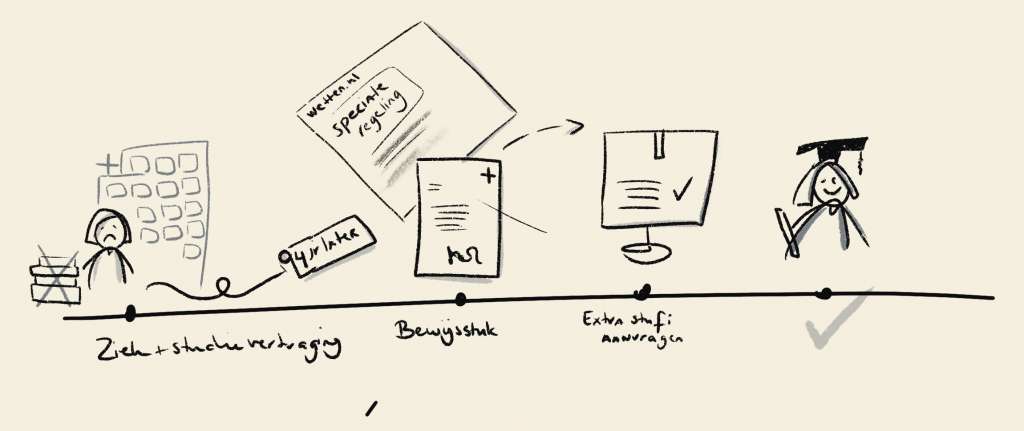

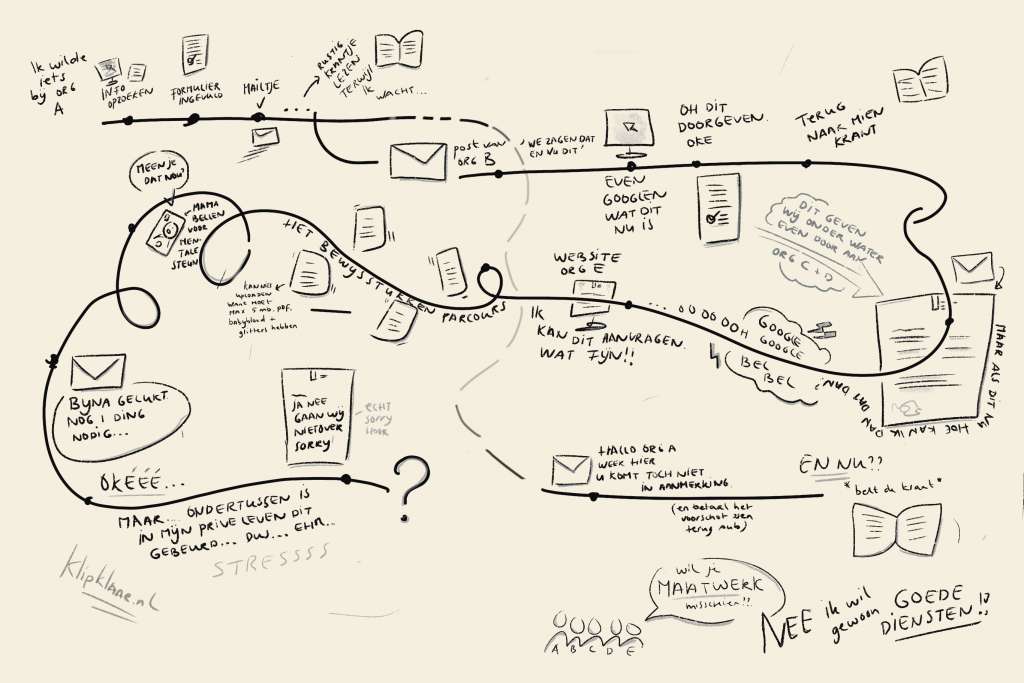

I began this research because I often felt unheard. I went to schools and community centers and came back with stories from students and refugees, but the process was already finished, the architecture already conceived, and policy was not what we were about at DUO. For the stories of these students and refugees, I needed other venues. Places to tell where people who did have policies about architecture and processes sat.

Yes, then you automatically end up in places of people with more power than you. Sometimes a little bit more, sometimes a lot more.

I noticed that these stories, as I told on UX Insight about the citizenship law, were not often told there. Understanding citizens is something for customer service, not IT or governance. The human dimension was not as cool then as it is now.

By now it is ‘cool’ and we know that in government we have created systems that are not good for people. The people who suffer from this are usually very different people from ourselves. They had no voice when we came up with those systems. We didn’t know them, we didn’t hear their stories and we didn’t look for them.

Apparently that is still the case in some places when I see the photo from yesterday’s IBestuur conference.

As I type this blog, I realize that Lou, Karin, Marije and Marlies are all blogging, writing, organizing, podcasting and telling what they think the world needs to hear. I don’t know if I would still be blogging now if I hadn’t had these kinds of examples (I don’t think so).

They create their own stage and then share it with others. They know we all learn more that way because we hear voices that otherwise don’t get space. They are not worried about whether there will be enough room left. Then again, they do invent new stages where there is even more room for diversity.

So, white man in suit, suppose you are asked for a manel, what can you do?

Is it enough to say up from the stage that it makes you uncomfortable? No. Make way. Don’t get on that stage and if you do accidentally get on it, walk right off. That would be equally uncomfortable for that small group of white men next to you, but it was uncomfortable for everyone else anyway.

Make room, there is plenty of room.