The Social Security Bank in the Netherlands once came up with the term ‘working from purpose’. You are faced with a complicated situation and think “what was ever the purpose behind this?”

Legislation is made from such a social purpose to organize and shape society in a certain way. We make policies for that, such as interventions of something that may or may not be allowed (manifested in permits for example a driver’s license), certain incentives (money you recieve or have to pay) or certain information that may or may not be recorded (in the Netherlands gender may be changed in a passport). Next, implementing organizations are in charge of implementing the policy, and thus are service providers.

In this blog you will find an exploration of what we (should) be talking about when we talk about services in the public sector.

I lean on the literature on service dominant logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). I learned about this at Karlstad University and wrote this blog. I also draw on practical experience over the past few years, as you can read in the archives of this blog, and on existing literature on service standards and service design.

As I delved into the literature on service-dominant logic, I frequently thought of that term “purpose”. SD-logic calls it: offering products or services to users so they can create value for themselves. That overarching value is essentially the service. I will explain this with an example that fits the Executive Agency of Education, where I work now.

Value is created in the classroom

I have long thought that in the case of the Law on Student Finance, the goal was met when a student could apply for student finance flawlessly. But it doesn’t.

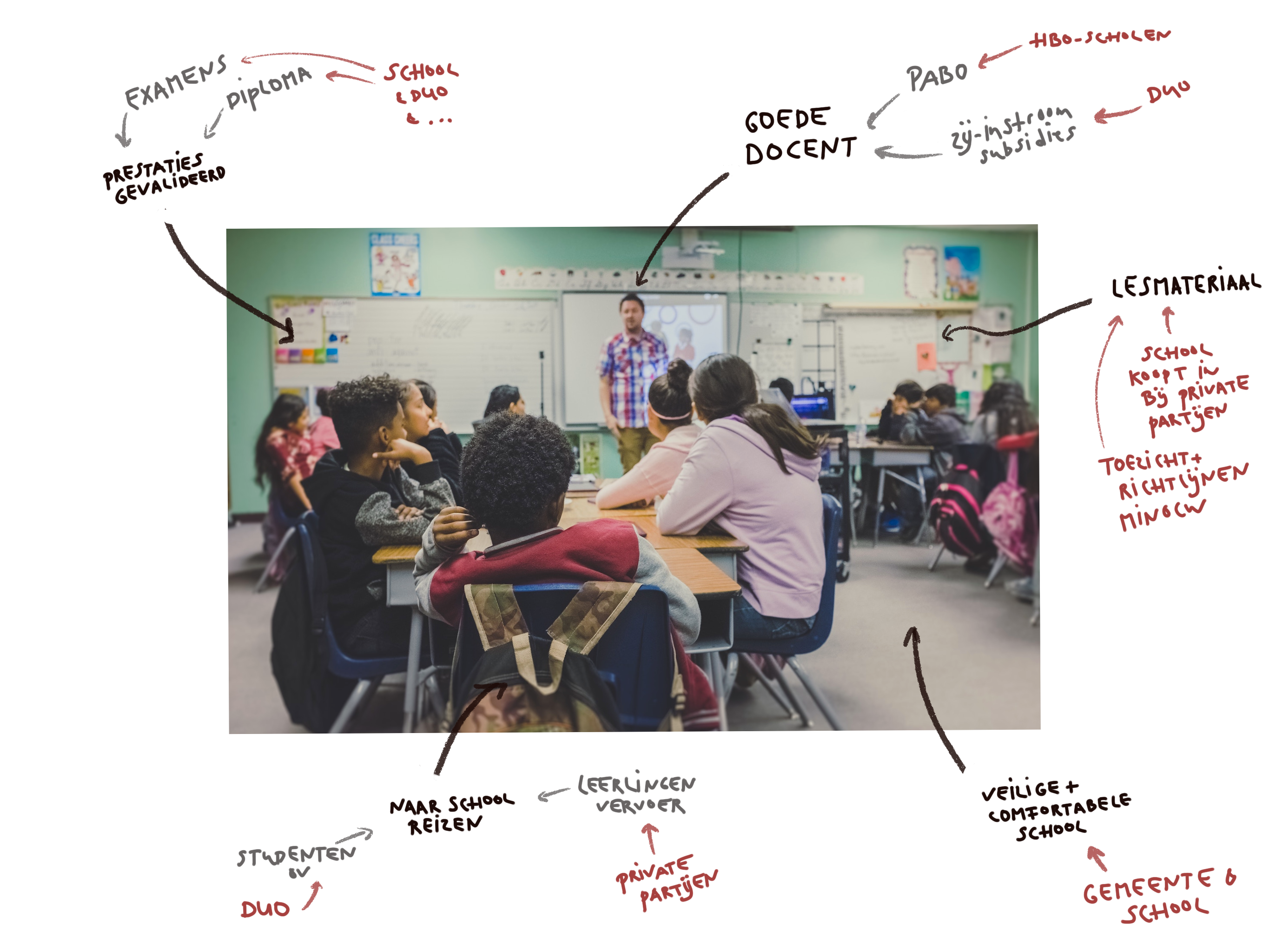

The goal is to develop yourself. To a large extent, the student must do this themselves, but we can help. I see that ‘we’ very broadly: government, society, we. To learn well and to make something of yourself, you need all kinds of things. I’ll mention a few:

- good teachers and thus teacher education, grants for professionals who want to retrain as teachers,

- a safe and comfortable classroom and thus a school board that can work with the municipality to achieve fine school locations, and can pay for it,

- good teaching materials, which is organized by the school, as well as private parties who write textbooks,

- traveling to school, using a student travel product or pupil transportation,

- validation of your learning in the form of exams and certified diplomas.

It looks something like this in my head.

Providing these resources so that a student can use them to develop themselves, that is the service.

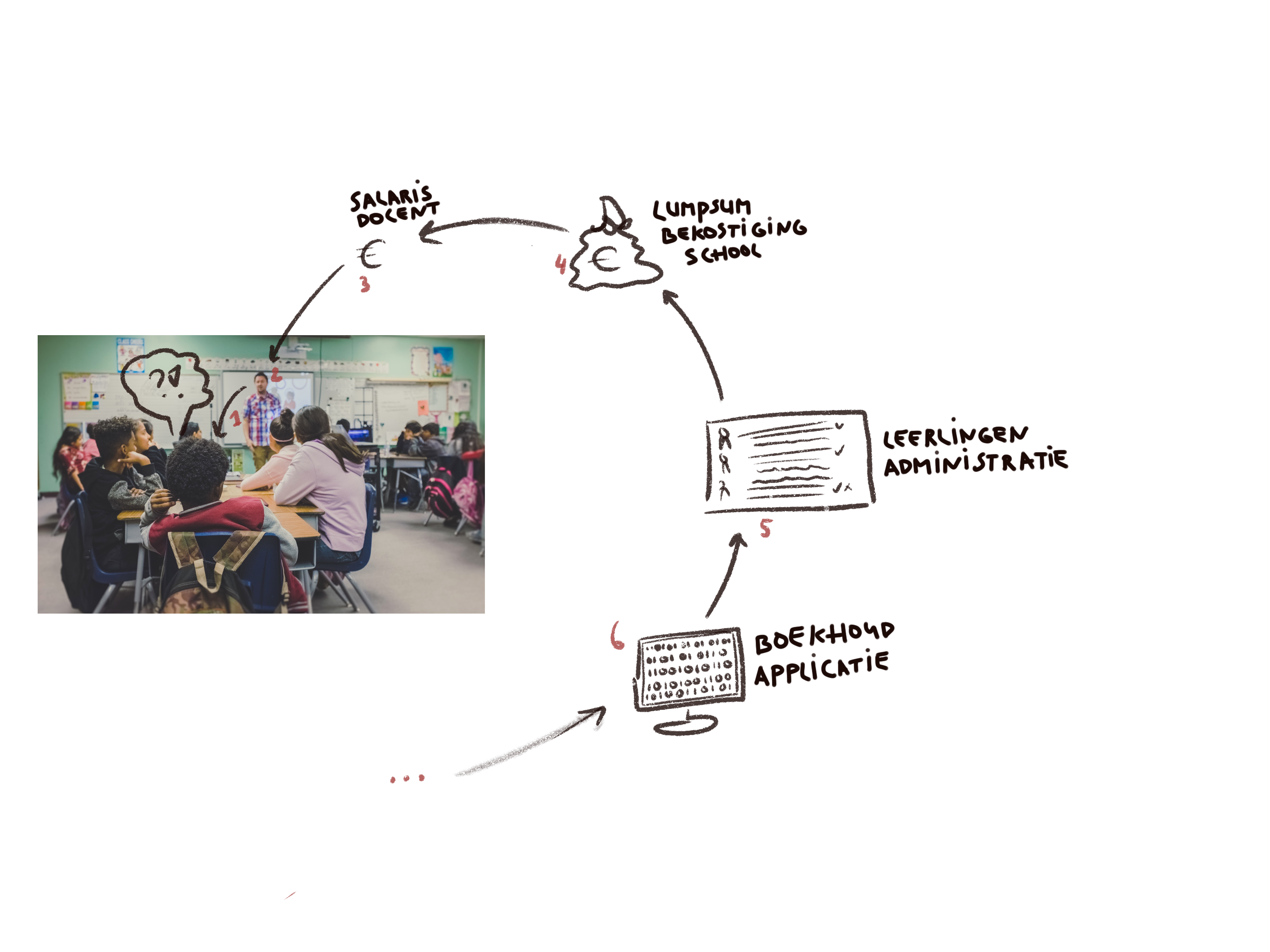

You already notice: some of these resources are sub-services. For example, an accounting application (a product) that helps a school keep student records (a service) that allows the school to schedule funding from the government (a service) to pay the salaries (another service) of the teachers (also can be seen as a service) who teach (a service) to the students who, if they do their best, learn as a result (hey, we’re here). A sub-sub-sub-sub-sub-sub-service.

Policy should be about value in the classroom, and so should the implementation of it. What does value mean in the classroom: is everyone allowed in that classroom? Can you learn without having breakfast? Does everyone have the financial resources to access the school? Are thinking skills worth as much as doing skills?

I’m making it very big now, sorry.

But I think it’s that big. All those (sub)resources eventually contribute step by step to those big questions. At the Executive Agency of Education, I’ve often heard that those questions “get political very quickly,” and of course we, the implementation should not be involved in politics. Fortunately, that is beginning to change a bit.

Not so easy

Much is known about how to create and deliver services. There are all kinds of standards, principles and processes for it. But they cannot yet be applied 1 to 1 in government.

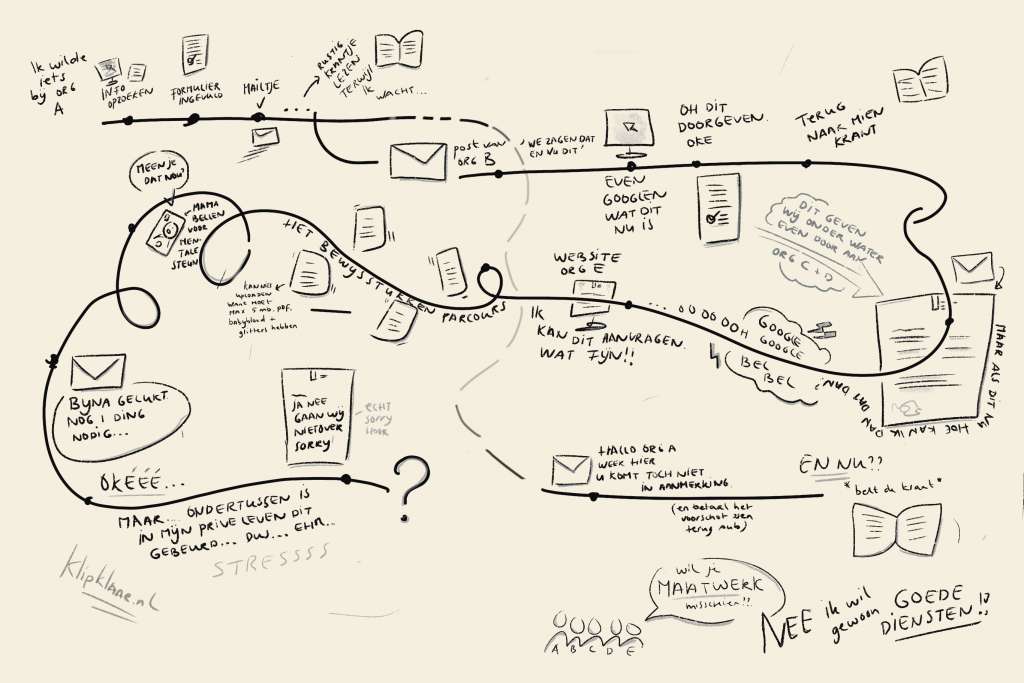

For example, the government is there for everyone, but can everyone create value for themselves? We know from the well-received WRR-report Knowing is not yet doing (Bovens, 2017) that we tend as a government to overestimate citizens and thus overwhelm them with resources, letters and things to do but lose track of.

In addition, there is tension on value for the collective and for the individual. The student loan system is a good example. Conceived as a cut to keep education affordable, but it led to a mountain of debt among young people in the Netherlands. Perhaps this actually made higher education less accessible. As a service provider, how do you offer such a service? So that students can develop themselves but do not run into sideways problems with their livelihood or future prospects? Should you make the application process for such a loan super easy and accessible, or difficult? I actually don’t know.

Executor or service provider?

The ISO standard on service excellence (ISO, 2021) states as its first principle that “the organization should be managed from the outside in”. Read: user feedback should guide how you create and offer services. That feedback is crucial, and should also be the basis for the policies you make.

In commercial businesses, you see that continuously listening to the target audience leads to new ideas of what resources they can offer so that customers will enjoy a purchase even more. For example: a friend of mine has an electric car with a built-in app that calculates exactly how long you can drive and where on the route you can recharge most conveniently (with good coffee). The company behind it is a car manufacturer, but knows that with apps like this as an extra service, you help the user in his goal: getting from a to b pleasantly and on time. The latter is the actual service.

In government, we don’t think that way yet. We are focused on the commissioning policy departments, and obediently implement what they come up with. Transferring student loans? Okay. Managing diplomas? Sure. Distribute funding to schools? We’re on it.

So we are executors. Being service providers requires something else.

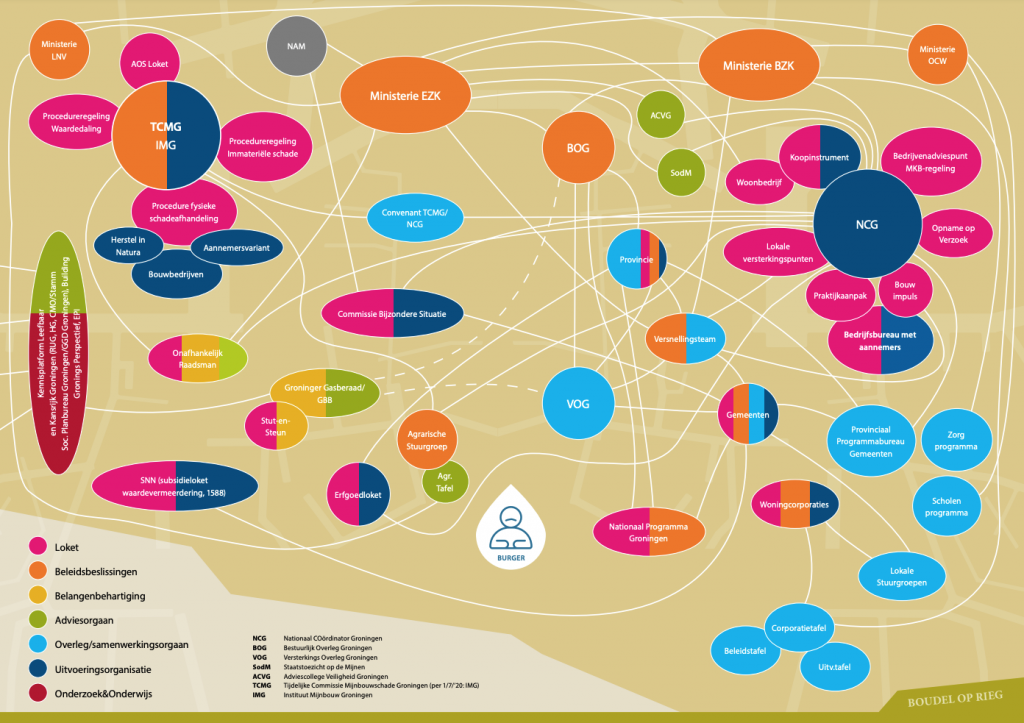

What if: we turn around and look at the classroom. Together with pupils, students and schools, and others in that service eco-system, we figure out what it takes for people to be able to develop themselves, how can we offer that to them in the smartest and finest way collectively so that the intent turns out in the classroom the way we wanted?

I am not a fan of Shell, but they do understand that for a fine car mobility experience, you need to offer services bundled and layered. The fast-charging locations connect to navigation services, there are fresh croissants, they outsource the coffee to Starbucks, all kinds of brands that together form an eco-system around car mobility and interact with each other.

Why not offer services bundled more often when we see and hear from users that they need them together? For example, why can’t you apply for student finance while enrolling in college? Research on the life event “Going to college” shows it belongs together. With both Studielink and MyDUO you log in with DigiD, in fact, the Executive Agency of Education uses the data from Studielink to decide whether you are entitled to student finance. But they are different organizations, with different clients, and we don’t perform under the same orchestrator. Unfortunately.

From arrow to lemniscate

See, with examples like this, it already feels a little less big and a lot more concrete how you can think of, design and offer services with purpose.

“But,” I hear you thinking, “you can’t sit in the policy department’s chair as an executor, can you? If the Executive Agency of Education comes up with the student finance law, wow wow… What about Parliament, which also represents citizens, right?”

True. There is a big difference there between the public sector and the commercial sector. Government organizations need to look both ways, both at the citizen in the classroom and the citizen represented in politics. I still find this quite difficult and am doing considerable reading in the literature as to what this means for service design and delivery.

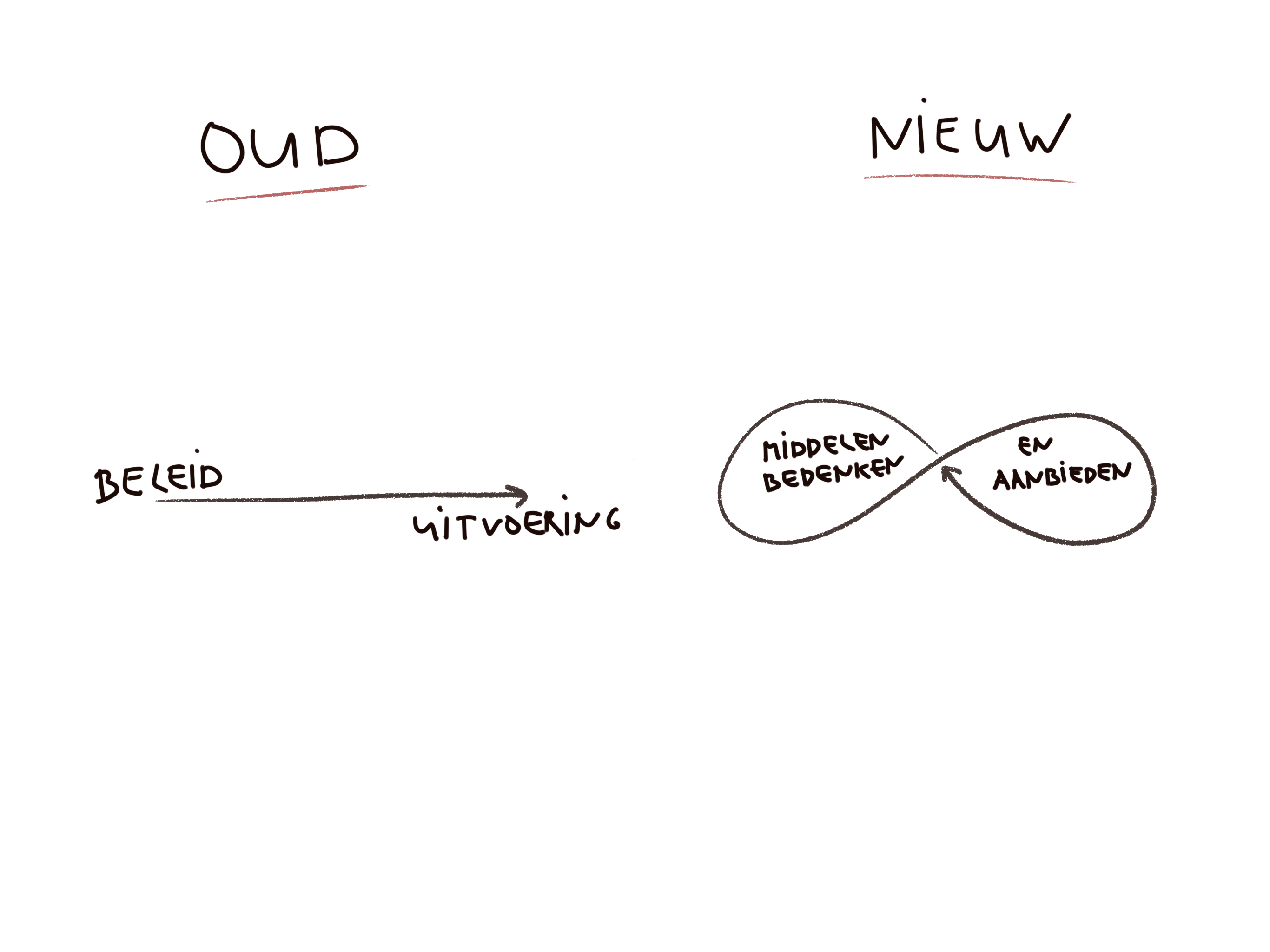

But I suspect that this strict separation between policy and implementation that we have very strongly in the Netherlands does not help. We should make the process of law to execution from a straight arrow from left to right to a lemniscate, an always continuous 8. Policy and implementation then are not so far apart, because devising and offering resources cannot be thought of in isolation, and certainly not without an understanding of how it plays out “in the classroom”.

I’ve tried it out with the education domain, which is nice and familiar to me. What would this look like around a topic like livelihood security? Around perspective on work, or care and health? And how do these domains overlap? That looks like a fun exercise for public service providers in the near future.

Follow my research and this series of blogs? Then subscribe to my monthly newsletter.

References and reading tips

The report on act-ability: Bovens, M., Keizer, A. G., & Tiemeijer, W. (2017). Knowing is not yet doing: a realistic perspective on resilience (No. 97). Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR).

ISO standard on service excellence: ISO. (2021). ISO 23592 – Service excellence – Principles and model. Geneva, Switzerland, International Organization for Standardization.

Article on SD-logic with almost cult status: Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of marketing, 68(1), 1-17.

On this page you will see a list of books and articles I use in my research.