You cannot achieve the best human-centered design for an interactive service without iterations. In a series of blogs, I cover the principles of human-centered work. Iterative work is an important part of that. That’s what this blog is about.

Want an update in your mailbox every month about my research? Then subscribe to my newsletter.

Getting it right in 1x

The other day I was at a meeting where two approaches were pitched on the whiteboard after a work session. One was a sort of intermediate step where a few things were temporarily taken care of. The other was the creation of a new law where issues could be thoroughly addressed properly. Both options had advantages and disadvantages. At one point, one attendee said, “We’d rather do it right the first time.”

I hear that more often in government. It doesn’t feel efficient to do things if we change it later. And it’s scary. The risk of something not being right and us as a government making mistakes (and getting in the newspaper!) is high.

Many implementing organizations have been involved in major service scandals in recent years, such as with the child care benefit, the WIA benefit or the student out-of-pocket grant. These issues have many different causes and consequences, but what they have in common is that they make organizations insecure about making new mistakes. This makes them reluctant to be creative and experiment. While that is exactly what is needed to make good services.

There are undoubtedly things in daily life that you can get right in 1x, but making services that people can use well, you can’t get that right in 1x. You have to learn, test and fine tune that as you go along. The ISO standard for human-centered design states that by repeating steps and seeking feedback in between, it is easier to achieve a desired result. By working iteratively, you can eliminate uncertainty during the conception and creation of services.

What is iterative work

Iterations literally means repetitions. When you create something, you do it in different versions. As soon as you have new information, you adapt policies, processes, systems, applications and letters again. In doing so, you reduce the risk that what you come up with will not meet the requirements of users and the societal goals at hand.

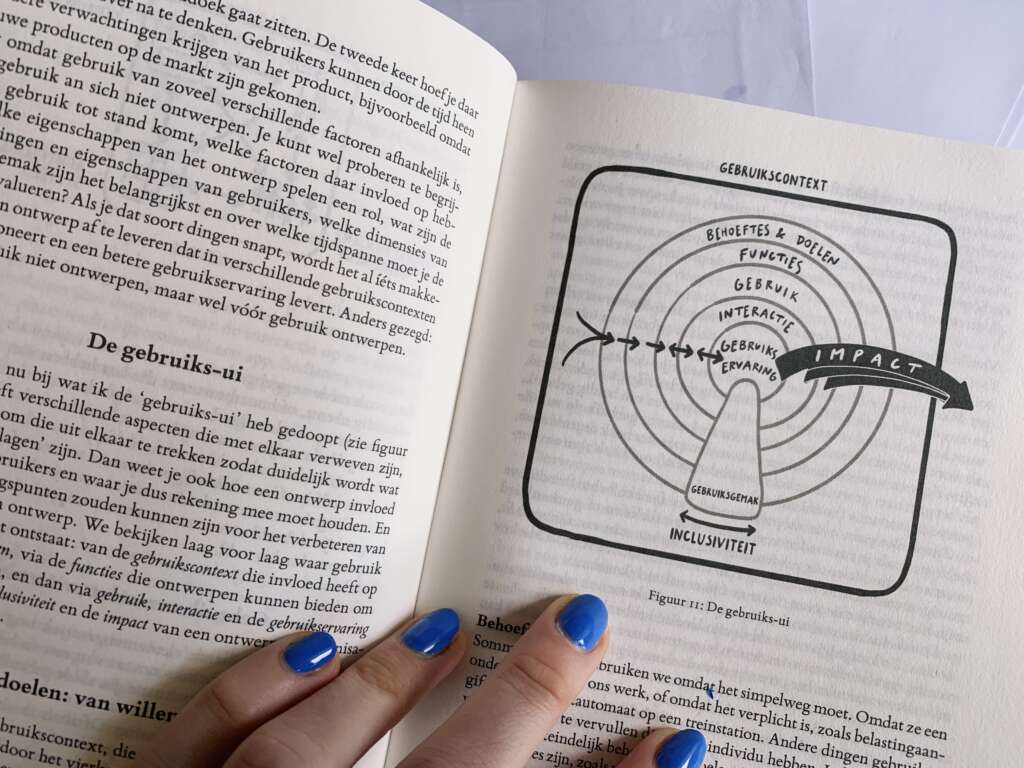

The complexity of how people interact with your service makes it impossible to fully know all the details at the start of your project. Many of the needs and expectations of users, as well as other stakeholders, only emerge during the course of the project.

It’s an interaction: as creators of services get better and better at understanding what their users need, they can devise and create something that hopefully fits that. Users can then provide feedback on that, upon which creators can adjust the services again.

Is this just agile working, or is it not?

Yes and no.

Most government organizations now work agile when creating applications. But working agile does not yet mean that they also work in a people-oriented way and make feedback from users leading in change.

In addition, making services consists of more than technology. It is incredibly valuable that ICT systems are no longer built in the classic waterfall way and are set up in a much more flexible way. The same should be true for how we make policy, for implementing organizational processes, for sharing data between organizations and more.

By themselves, many officials are quite used to creating different versions and incorporating feedback from colleagues. Policy papers go around mailboxes and grow from version 0.1 to 0.9. But once something has version 1.0, the memo has been to the Stas, a law is in the Government Gazette, then it is – sort of – finished. If you notice at a later stage that things should have been done differently, just take a few steps back. That’s why you have to develop policy and implementation iteratively at the same time, so that one can give input to the other and vice versa.

It is precisely iterative practice in practice that provides many valuable insights. I follow an example of how to do that in my doctoral research with the Clustering National Debt Collection program.

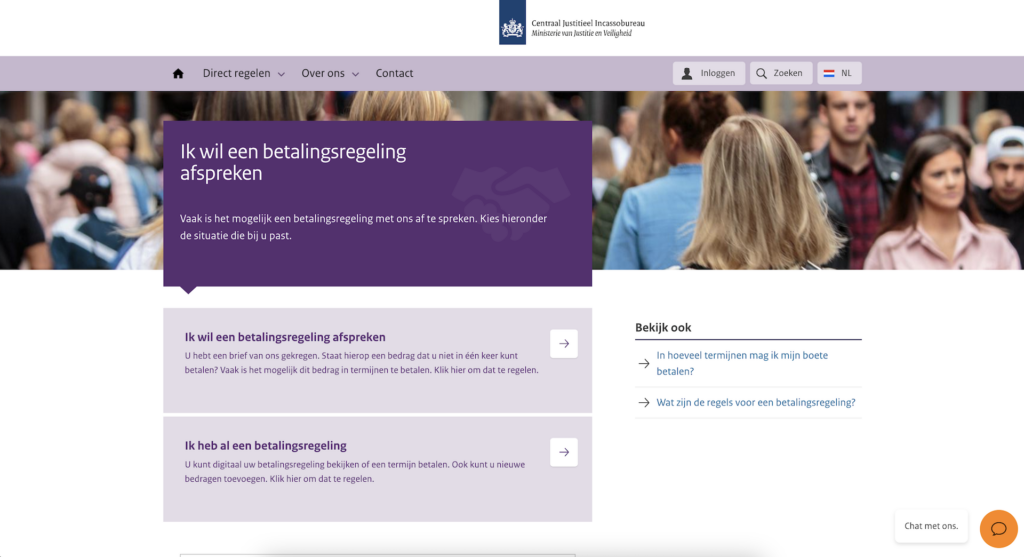

When someone has debts with several government organizations, they can agree on one payment arrangement with the CJIB. At the back end, CJIB controls which organization receives which amount. Two years ago this payment arrangement started with a small group of claims from DUO, CJIB and CAK. Since then, a few more organizations or types of claims have been added each year.

While it is unfortunate that not everyone in the Netherlands can apply for the scheme for every type of debt right away, CJIB can now learn in practice how the scheme works and what it takes on the back end to redesign the way the government collects debt. In this way, they are learning in practice how best to bundle policies and how to increasingly expand this to include more claims from other organizations. They do usage research on people currently using the scheme and learn why people do or do not persist with a scheme. They use those insights to adjust the policy and implementation of the scheme again. The experiences from the current scheme are also used in conversations with other organizations about how they can connect. In this way, the service continues to grow iteratively.

Iterative making or iterative talking?

Look, per se, in government we have quite a talent for iterative work. But working iteratively without making it gets bogged down in iterative talking. Constantly bringing things up for discussion, from different points of view, it sometimes seems like projects don’t move forward.

That is also iterative work, but not what I mean in this blog. In fact, getting real-world input and testing your idea or design with people who will use it will help move your project forward.

The best way to do that is to make things tangible. How to do that, I’ll tell you soon in an upcoming blog.

I also do my research iteratively, together with you

It is now second nature to me to work iteratively. This is also how I approach my doctoral research. Sometimes it makes me insecure: can’t I think of anything myself? I regularly have versions of articles read by others. My supervisors at the university, as well as readers of my monthly newsletter, regularly comment on preliminary insights and/or read along. Therefore, it also means working openly and transparently.

It is exciting to show something to another person that is not yet finished. You tend to immediately add a hundred things you want to improve, and to cover yourself, but what for? My experience, both with my current research and before when I did user research for DUO and the Corona app, is that people like to give feedback, to help test and help get the job done together.

How do you begin?

Start with the problem and not the solution. When it is shouted in the House of Representatives that “Organization X should also have an app,” yes, you can’t really do anything else. Therefore, start not with a product or concrete solution but with understanding the problem and start from the whole experience of your target group and not just your own organization. Engage users and then consider together what outcome you would like.

For example: it is a problem that many people in the Netherlands are in debt and cannot get out of it themselves. The government itself also plays a role in this as a creditor. How can we as a government solve this problem by collecting debt socially? The outcome: fewer people in (problematic) debt through better services! What kind of service… We design that iteratively together with users.

And: work openly! Share your work, actively seek input from stakeholders including your users. Open working is exciting for government. I previously wrote this guide on how to do this practically.