How can you make government services that are good for people? To explore this, I look at the principles of human-centered design. In a series of blogs, I’ll cover them one by one. That way, I’ll start to understand them better and better myself.

In this blog, the second principle: design is based on an explicit understanding of users, tasks and environments. What is it, how do you do it and how do you start? Read the first principle back here.

Want an update in your mailbox every month about my research? Then subscribe to my newsletter.

Elephant trails

The first time someone explained “usage” to me was accompanied by the example of elephant trails. You know them. You may use them yourself or have even made one at some point. The municipality has built a neat sidewalk, but the most convenient route is just along here, between the bushes. And there you go, off the designed path.

Jan-Dirk van der Burg made a wonderful book about it. On his website he shows how a number of elephant paths are still being hard fought by municipalities, such as in Leiden:

Van der Burg writes: “In Leiden, there is an innovative experiment with three parallel hedges, it looks a bit like a military course. The municipality only made a rookie mistake. The hedge just doesn’t connect to the pond area, so then another…”

You see: designing something is perfectly possible without considering its use.

But if you want to design human-centered , you can’t avoid looking into how people want to use something and in what context the use takes place. This is true in public spaces, but equally true with products such as electric toothbrushes or government services such as using WIA benefits.

What is usability?

This is the extent to which a system, product or service can be used by certain users to achieve certain goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a given context of use.

Definition usability from ISO standard 9241-210.

When designing products, systems and services, you must consider the people who will use them, as well as people who may be indirectly affected by their use. It is therefore important to first know who these people are. Building systems without understanding who will use it is one of the main causes of system failure. Thus the ISO standard human-centered design for interactive systems.

Whether products or services are useful depends on the context in which they are used. People may have different goals when performing actions with your product or service. In the blog on the principle of “Starting from the whole user experience,” I showed how his-goals, do-goals and tasks relate to each other.

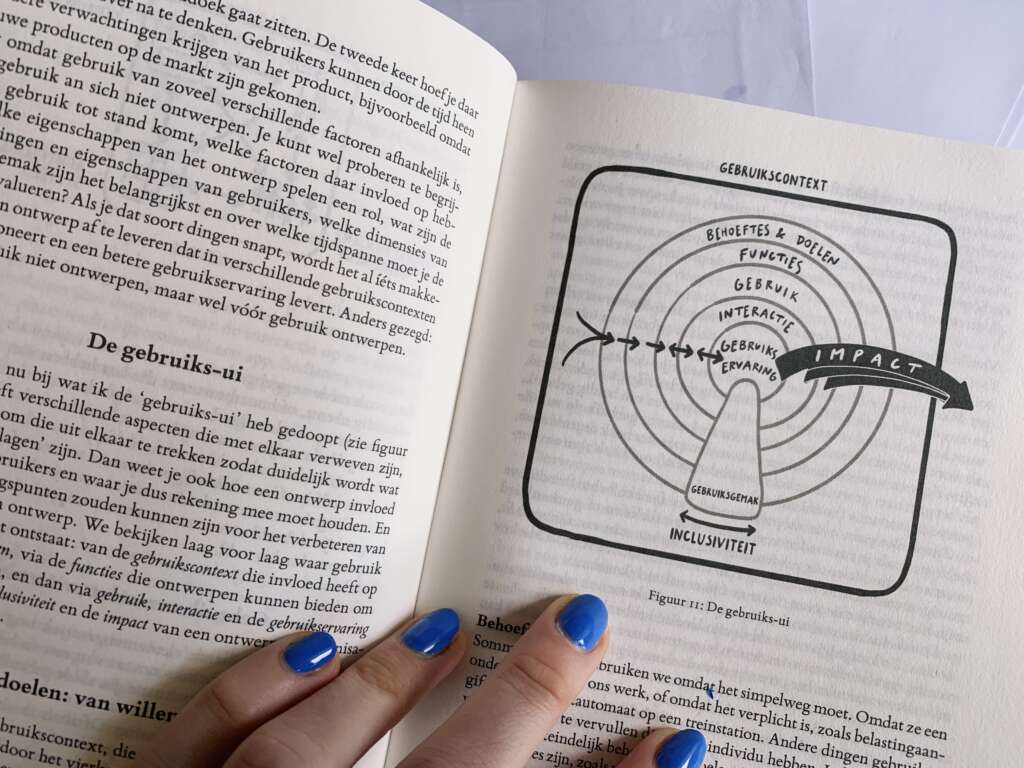

I find that in practice, when people think of usability (or the English “usability”) they often think that buttons should work conveniently on a Web site. But it is much more than that. In his book ‘How easy can you make it’ Jasper van Kuijk explains this with ‘the usabilityui’. Use of a product or service has several aspects that affect each other.

Van Kuijk argues that needs and goals combined with features what a product or service can do makes you use something. Interacting with a product or service allows you to achieve your goal. Next, the user experience is what it does to you while you are using it.

‘Unintended’ additional interactions

An example: in December, my husband and I decided to end our joint business. As real salaried millennials but with creative side hustles, we were also getting a bit older and the side hustles have actually not been around for a while. I went to the site of the Chamber of Commerce, through the drop-down menu to form 17 to deregister a limited liability company. The form needs to be printed, so I to the copy shop in my neighborhood. Then to the Hema for an envelope and then to find out that, yes, on New Year’s Eve the mailboxes are of course sealed, so the whole thing has to be mailed a few days later.

My goal was to write out the vof. A digital function was missing; it had to be on paper. I suspect because of the double “wet” signature. Or perhaps more simply, that digitizing this process is still in the planning stages. However, it significantly affected my user experience. With this, my visit to the Copyshop and to 2 Post-NL points became part of “the customer journey” of the CoC. There was no elephant path, indeed there was a significant detour.

Next, van Kuijk contrasts ease of use with this. This is not a separate layer of usability, but a cross-section of all the above elements. If user experience is what it did to me (emotion), then ease of use is what I could do with it at all (accessibility). Let’s face it: for Henk, my dad, signing out on paper would have been a piece of cake. He has a printer next to his desk with no dried ink and a tray with several sizes of envelopes. And who doesn’t usually start figuring out how to get the job done 1 day before the deadline either. But yes, his daughter unfortunately does.

A design strategy may be to serve the largest group, which is what many commercial companies do. Are there more potential Henks in the target group? Those don’t mind making a print, even make an extra one for their own records. Or are there more Maikes in the target group, then you lose sales if you don’t offer your services differently.

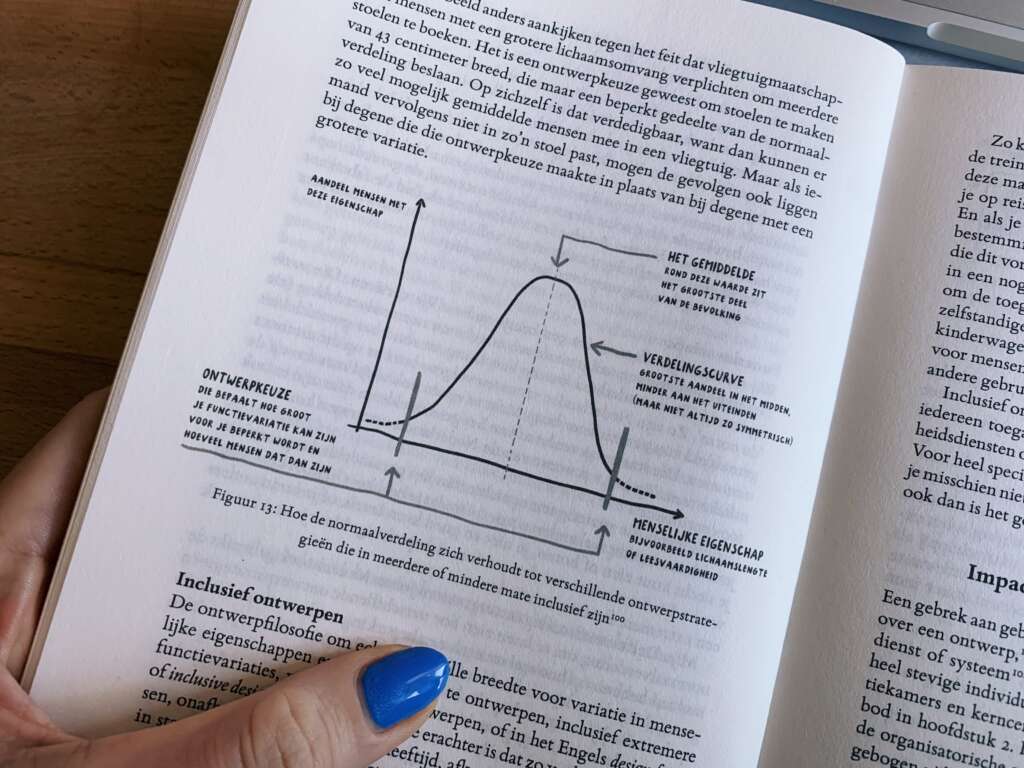

Or as Van Kuijk draws it beautifully in his book with a normal distribution:

But different rules apply to the government: they cannot choose who they do and do not serve. They have both Henk and Maike in their target audience. The government has to make services for everyone. I could only achieve my goal with this one organization.

The same principles apply to a variety of other products and services. An extra sink at the McDonalds at kid’s height. An e-reader (without blue light) for when you’re still reading in bed at night. Being able to pay a government fine directly with a QR code. A coffee mug with a handy push button that doesn’t leak when you slam it into your bag. Tikkies! Komoot that reads the route flawlessly and on time, while you are running in the woods and you can foolishly follow the voice. Just some products and services that fit exactly with use in context.

How do they do this?

How do the organizations behind these products and services manage to design them so that not only can people achieve their goals with them, but they are also so tasty to use?

They research how and in what context their product is used. For example, one of my favorite running apps was created by people who are avid runners themselves. They understand me and what I need. But even if you don’t match your user, you can research what someone needs and in what context they use your product or service.

For example, by:

- Target your audience in their own environment. If you make services for students, walk into a university cafeteria and strike up a conversation. Are you working on services for people in debt? Take the time to hear the stories people are dealing with. Visit people in their own environment instead of hosting sessions in the office. It is precisely in their own environment that you understand how things impact each other. Observe how people use your service. Ask for examples and if they want to show you something, not just tell you about it.

- Then engage in structured work to map usage information. Do focused in-depth interviews and observe several people while using existing services. Determine what their specific needs are. Fill in Van Kuijk’s usui based on your research. Let this guide the decisions you make during design.

These are also called the first two activities of human-centered design from the ISO standard.

Continue reading?

- What is human-centered design? All the principles and activities based on the ISO standard at a glance.

- The usui comes from: J. Van Kuijk (2024), How easy can you make it? Atlas contact.

- Jan-Dirk van den Burg, 2011. Elephant trails. A series on the tension between planning mishaps and human instinct.