Yesterday I attended a session on Health in Groningen: a special government for vulnerable citizens. The afternoon was organized on behalf of the Province of Groningen, and I got to kick off the conversation with a short speech together with Albert Jan Kruiter. Albert Jan began and talked about the breakthrough method and why it was needed for the roughly 20% of our population who, despite (or perhaps because of) interference from many institutions, are no longer getting out of trouble.

You can read my speech below; I am posting it in full.

Don’t miss a blog? Sign up for my newsletter.

‘Build the right thing, build the thing right,’ is a well-known saying in the design world (Buxton, 2010).

But what is the right thing, and how can we make it right?

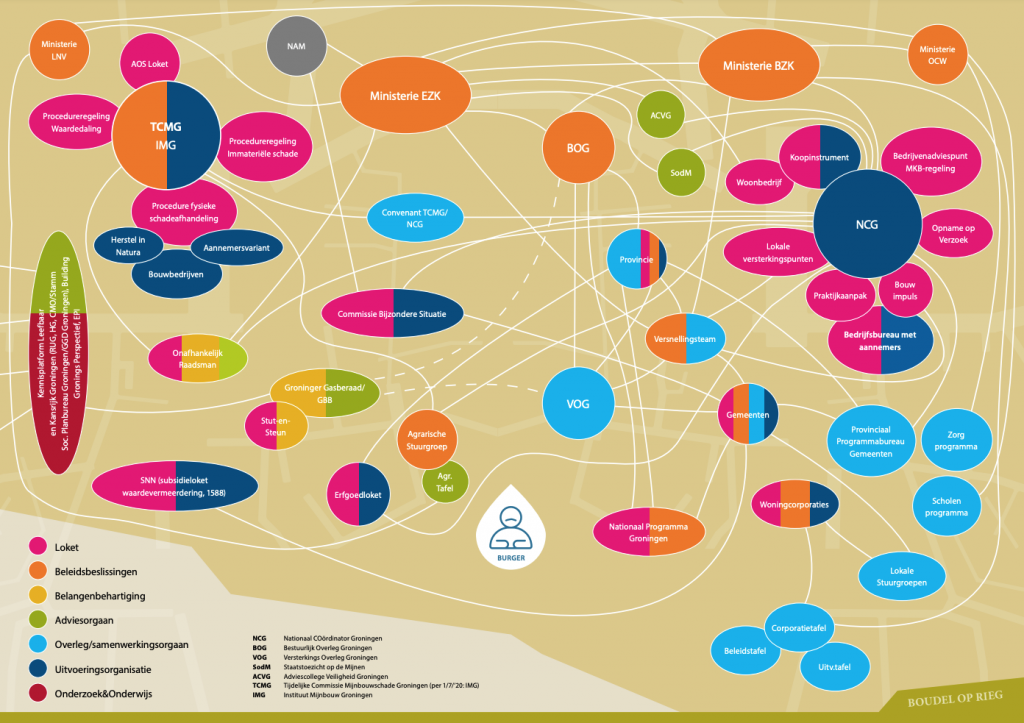

Besides the regular patchwork of social security benefits, which Albert Jan just spoke excellently about, Groningen has another coarsely knitted plaid on top: the earthquake problems.

Recently, the Cabinet announced 50 measures to address these problems. In which I like that they see, now more than before, what is going wrong. But even in these 50 measures, what we also heard in Albert Jan’s story continues to shine through: no integrated approach to the whole problem, rather: something here, and something there. The problems are taken apart in the analysis, and then solved separately, but what they forget is that with residents it can never be taken apart.

What is still missing is an overall picture of what, for example, a household in an average Groningen locality can now expect, especially for the group that has the most damage. I won’t go into detail about the various components of schemes, or the issues themselves: I look around and see that the public here is extremely knowledgeable about what is going on in our region.

What gives me hope is that those measures do include a Social and Economic Agenda, which hopefully we do start to set up in an integrated way. That could be a start for building the right thing.

But even when we build the right thing, I still worry. For will the right thing also be rightly build? That concern about “building the thing right” is something I want to explore with you today.

Is the right thing rightly build?

I think of a lady in Appingedam whom I visited two years ago. She bought an extra bookcase for all her administration.

Imagine it.

A billy bookcase especially for all your earthquake stuff.

Let’s look at 1 paper from such a closet I take a letter I received myself.

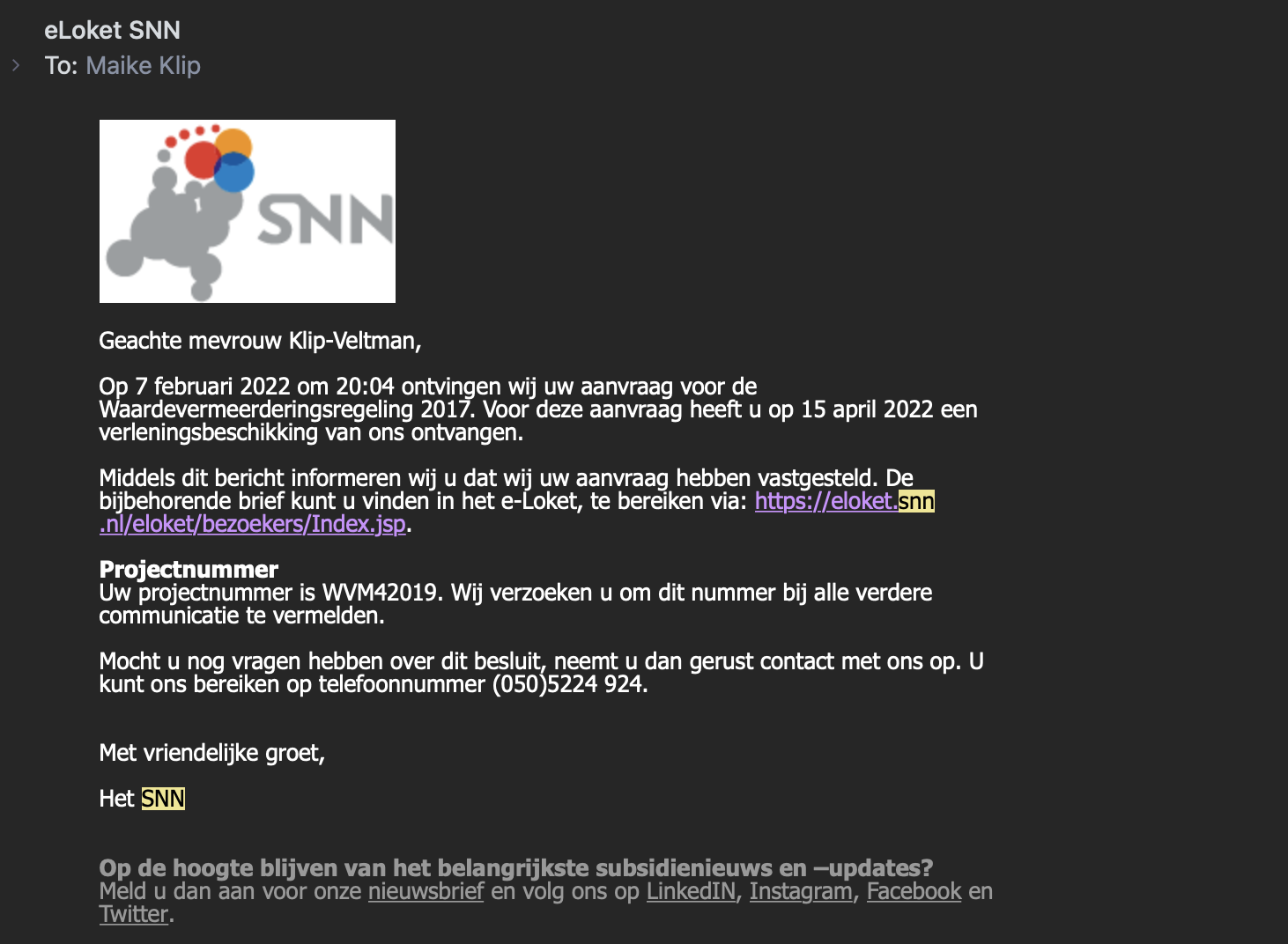

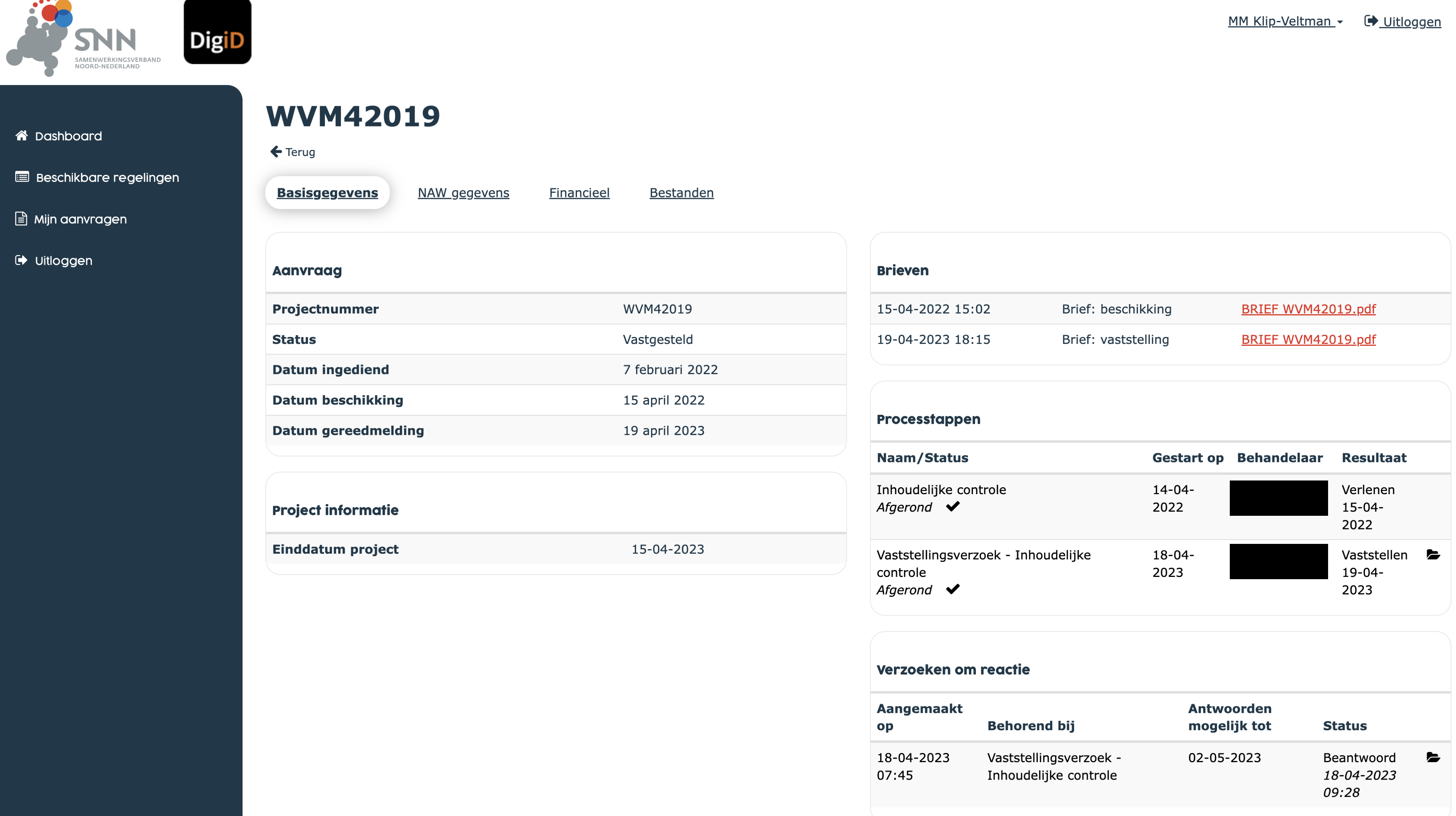

I want to start by saying that this is a fine arrangement that many people in Groningen are grateful for. Apart from that lack of integrality, this is really a bit of “build the right thing”: the €4000 grant for sustainability at the SNN. I applied for it myself last year for the windows at the back of my house.

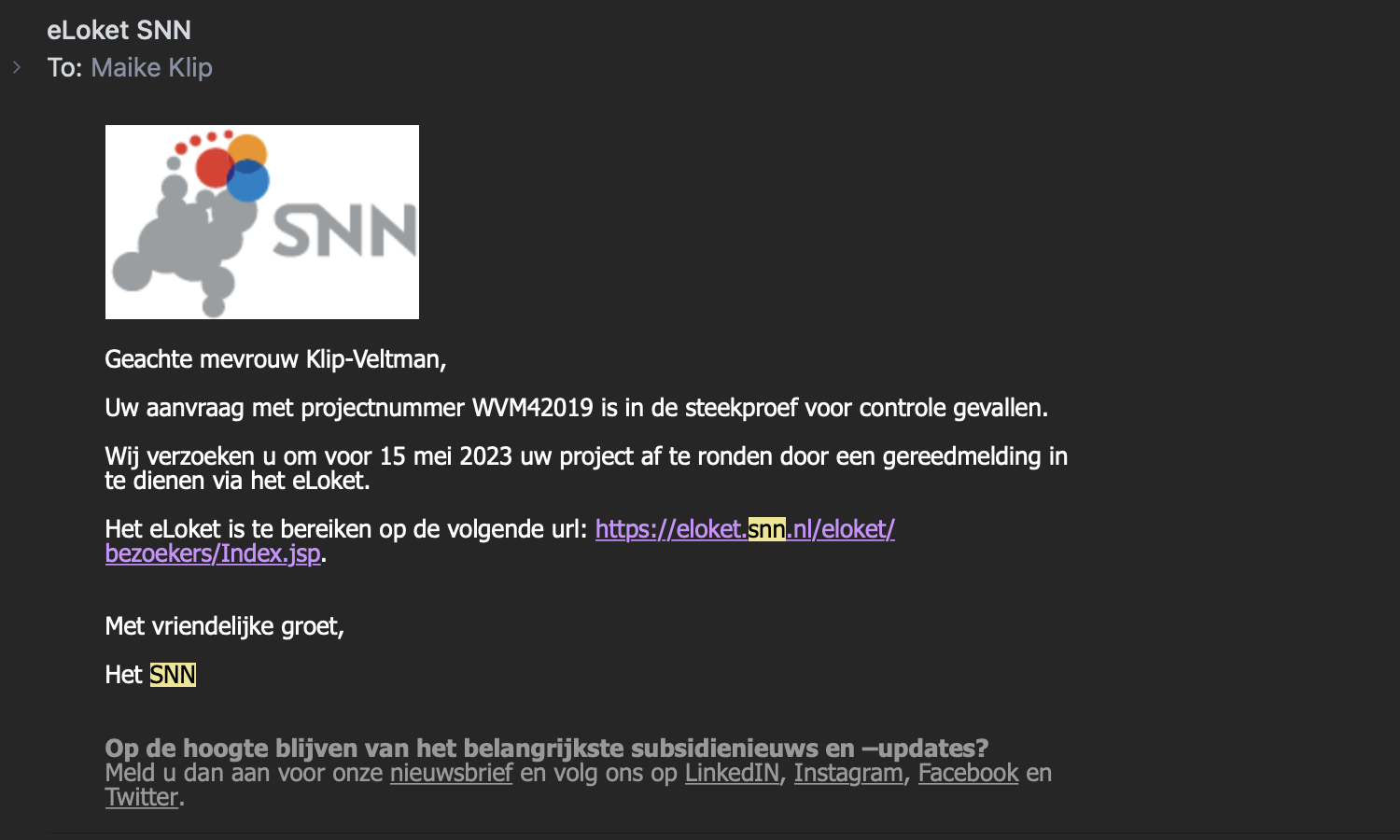

A few weeks ago, I received an email that I fell into the sample. I had not heard anything about it for over a year by then. I had to show that the windows were actually installed. No problem, I looked out through them, proof enough.

But here is the thing… I had asked my contractor at the time to do a new quote for the windows because the quote I had, which was actually an invoice and it said all kinds of things more that he had done to our house, that quote was not accepted by the system. It did not have the right things on it, including the right date for the application period, nor the exact description of the job. So I got a nice new quote that met all the conditions perfectly and arranged the application with that. Nothing wrong, I thought.

But now with that sample I also had to send the invoice, of which I had no separate one at all. The invoice was even a few months in the past in terms of date. The proof of payment, a statement from my bank, was also months before the offer date and belonged to that earlier invoice. By the way, it was also a different amount than was on that new quote. Had I faked it now?

Well, I uploaded everything. By the way, there was no way to upload before and after pictures, it was purely for administration. Fortunately, there was a field near it where I could put something of a note and well, here’s to hoping.

I worried

I was talking to friends about it. I whined to my husband about it. I got angry. Because I had modified that whole quote in the first place because the reality that was there did not fit the application system. I thought up – obviously with my eyes peering at the ceiling in the dark – an angry speech for how none of this could be my fault and I wouldn’t have to pay back that grant. I cannot deny that some of that angry speech is now in this speech.

And then I got an email that the application had been completed.

Okay … completed what?

Good or bad? Can I keep it, should I give it back?

I could not see it clearly in the portal except that the case was “fixed”. I was hoping for a who’s-the-mole green or red screen, or something of a sign, but after some clicking through, I found this letter and read that I was indeed getting a grant. After which I drew the conclusion that this was the end of it.

Now you may be thinking this is not a good example.

Because it all worked out. It turned out to be a storm in a teacup; besides, I’m not a vulnerable citizen at all, right? I am smart, I have studied, I have a partner who listens patiently to my whining, I have a house, in the city of all places, so I shouldn’t say anything, and I can even cope financially if I had to pay it back.

But still… this feeling I had, like I was stupid and didn’t get it. That instant stress that I was being peeved anyway, and that I was thinking all the time ‘what would they want to hear’ and trying to write the application towards that…

As if there are two realities

A paper one that I had to mold myself to and put in the application so I checked the right boxes and got the grant. And the real reality, that of my windows that I can look at while uploading the documents. And which are actually now of double instead of single glass. But whose administration – as it had gone – did not fit perfectly into the application process, even though the arrangement was intended for exactly these windows.

That feeling is what philosopher David Graeber (2015) calls the “stupidity of bureaucracy. That feeling that bureaucracy makes you stupid. That you think “this is on me.

As a designer, I have learned, “it’s never the user’s fault. It is never down to the user, processes and systems must serve the human, the user, and never the other way around! Build the right thing, and build the thing right

Back to the folder. This is 1 paper.

I could have taken a much harder example from residents in Groningen. I could have chosen defense papers. Intimidating letters from the country’s attorney. Lingering email exchanges with the NCG about house reinforcement. Or with the municipality about the community center. Or the icing on the cake: everyone remembers those lines for the €10000 grant on Jan. 2, 2021.

Apart from the fact that all these separate arrangements are not the right thing, they are also poorly made

Letters that are not clear. Portals where you have to search for what you need to know. Application forms where you feel stupid and have to empathize with what they would want to hear. Or that are just clumsy because you read while filling out the form that your attachment should not be larger than 5MB and you don’t know how to convert that right away so you then get kicked out because you have not been active in the portal for too long.

In addition to new individual pots of money, the cabinet response announces a new digital portal and communication ways. There is also investment in earthquake coaches at the same time to stand beside people, Stut-and-support gets an additional grant.

Today we are going to talk about the health of people in Groningen, and the relationship between the government and citizens in this. Special government for vulnerable citizens. I think it’s commendable, I sincerely believe, that the province, and the Groningen National Program are thinking about this. But I can’t help but see the irony in this as well. “The government” – it doesn’t exist, of course, but let’s pretend for a moment that there is such a 1 government – wants to create a nice, good treatment plan to increase the health capacity of vulnerable people.

But let’s also take a look at the patient’s diagnosis.

Imagine how many papers fit in 1 folder. And then how many folders in a Billy bookcase? Then tell me what people in Groningen are getting sick from now?

It’s from this – mostly government-generated, poorly made – billy bureaucracy.

References and reading tips

Buxton, B. (2010). Sketching User Experiences: Getting the Design Right and the Right Design: Getting the Design Right and the Right Design. Morgan Kaufmann.

Graeber, D. (2015). The utopia of rules: On technology, stupidity, and the secret joys of bureaucracy. Melville House.

Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate, 2023. Nij Begun, on the road to recognition, recovery and perspective.