This month I write about my new research on government services that are good for people. I wrote the big plan and the journey so far. In this blog you can read about the approach and an initial planning for the coming years.

You can sign up for my newsletter. Once a month you will receive a summary of the research in your mailbox. This way you won’t miss anything and you can easily respond and participate in the research.

Choosing the approach

A number of personal considerations quickly helped me decide how to approach this research. For several years now I have enjoyed working across government, from the perspective of citizens who have to deal with the entire government. During my master’s, I really enjoyed the critical sparring with an external institute. I therefore contacted TUDelft to find such a construction again. In the form of a PhD research I was able to find both an excuse to work government-wide and to collaborate with a university.

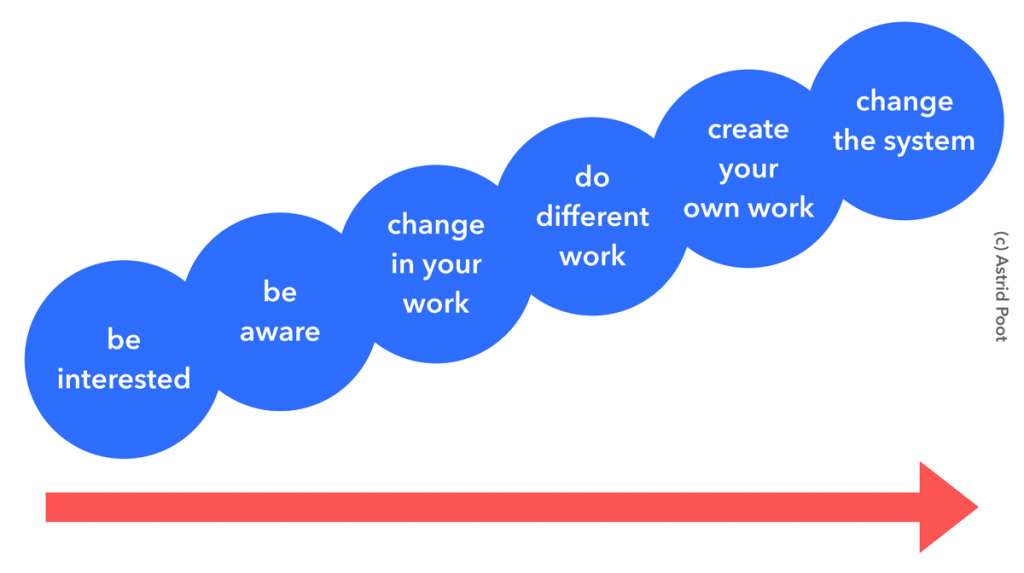

But… I am not concerned with ‘just’ producing new knowledge. No, I want us to learn how to work from a human perspective in practice at the government. And of course I have developed my own design and research skills in a certain direction in recent years, which you have been able to read on this blog since 2017.

An approach that fits well with all of this is action research. To me that is open action research because I blog about every step. Not only the result is open, but the process while we are working. So you have every chance to adjust the process!

Combining practice and theory

Action research is not your average scientific research. It is a much more practical approach, which is why I will not be working at the university in the coming years, but at the government’s implementing organizations itself. To research from the inside in practice together with colleagues.

Research that starts from the problems generated by organizational contexts and focuses on change requires a radical reappraisal of the relationship between knowledge and action, and of the related image of the ‘academic researcher in an armchair’.

Van Marrewijk, A., Veenswijk, M., & Clegg, S. (2010) ‘The organizing reflexivity in designed change: The ethnoventionist approach’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(3): 212‹29

Action research has a number of properties that suit me and the issue well. Action research is:

- in the situation: it requires direct involvement with real and complex problems in the natural context

- relationship-based: we learn through relationships with stakeholders who all have different perspectives and contribute in their own ways to understanding and solving problems

- focused on change: together we look for ways to initiate, promote and manage change

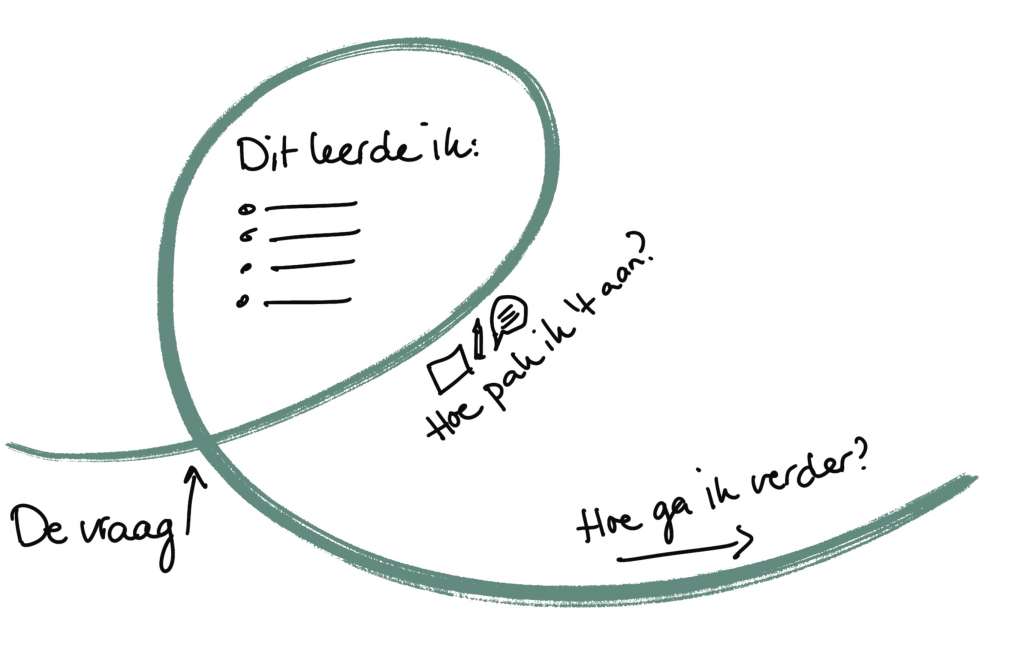

- reflexive: we continuously (in action) critically consider our own practice; I as a researcher and together with all participants. We learn together and an open and explicit learning process is created.

From: Giuseppe Scaratti, Mara Gorli, Laura Galuppo and Silvio Ripamonti. Action research: knowing and changing (in) organizational contexts. In: The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods: history and traditions, 2019.

Reading tips

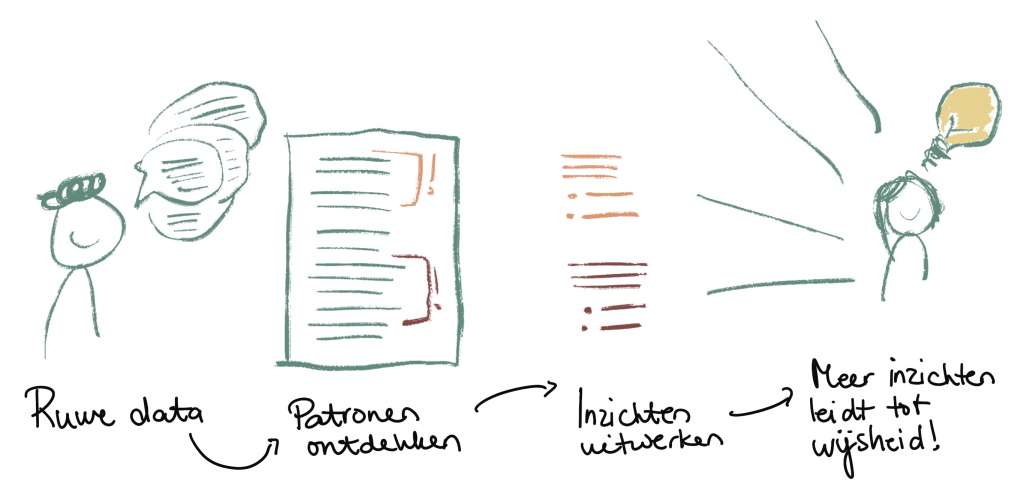

In the near future I will learn more about this way of doing research. During my master’s I learned a lot of practical skills and now I’m also immersing myself in the methodological background. In addition to the article from the previous section, the following books are very helpful to me:

- Introduction to action research, social research for social change by Davydd Greenwood en Morten Levin. This book provides a good overview of the background of action research and a number of examples of different trends and approaches.

- The reflective practitioner by David Schön. I already read this while making the photo interviews from The compassionate civil servant. Very good book about reflecting while you are in the middle of it all, about reflection-in-action.

- Doing action research in your own organization by David Coghlan. I’m reading this one at the moment. Much corresponds to the approach I also used with The compassionate civil servant, but it is much more extensive and explains action research in a more fundamental way.

Role of this blog

If you’ve been following my blog for some time, you might find it super logical that I’m going to write about this research. That’s how it feels to me too. But in the near future this blog (and the newsletter) will have an important function.

I once started writing as my own archive, for myself and the handful of colleagues who might also find it useful. Later it became a place to document my research results and after that a place to participate in the social discourse about the human dimension in government.

Since October I speak to my supervisors Maaike Kleinsmann and Jasper van Kuijk every month. They noticed that I often quickly determine how something should be interpreted when it comes to government. “Yes, that’s just how the government works,” I say. I have been a civil servant for 10 years and, through this blog, I hear so many stories from you about how your organization is doing, that many things are so self-evident to me. That’s all tacit knowledge that I myself sometimes don’t even know I know.

By writing I make my own thoughts and choices explicit. And by sharing you can react to it and add knowledge and new questions. This is how we reflect together in action.

Then the schedule

This is a long-term project. It will certainly take several years. Overall, I look at it something like this:

Year 1, we are in the middle of this, is a year of preparation. Important is:

- setting up the project and connecting with you and other stakeholders

- dive into the literature and build a foundation for the years to come

- make a concrete research plan for the following years, including agreements with organizations, make a data management plan, pass the ethics committee, and probably more that I can’t yet oversee

- working on my own skills, because it’s quite a different story doing PhD research

Year 2 and 3 I will work in practice together with public service organizations. For example, I might come to work in your organization and together we create a service from A to Z from the perspective of the citizen. Together we reflect and learn. In the coming year I will develop this further and I will also share which criteria such a case preferably meets.

Year 4 consists of finishing. Insights become shareable and beautiful end products are produced. This will be very practical and applicable for everyone who helped and theoretically in the form of a dissertation.

In the next blog, which will be online soon, I will share more about the first year, especially about diving into literature.