Yesterday, more than 100 researchers working in the Dutch government met in Utrecht. The government-wide research community held its first real-life event, and the organization had to ask participants to attend with just 5 persons per government organization. If you had told me this 10 years ago, I wouldn’t have believed you. So many researchers already work in government. Super.

In this blog, I share my presentation: about the context in which we work and why researchers are necessary for good service delivery. We look back at how far we’ve come, and also ahead: what will it take to let the lifeworld of citizens guide the delivery of government services? I call that doing full circle research.

An update in your mailbox every month about my research? Subscribe to my Dutch newsletter.

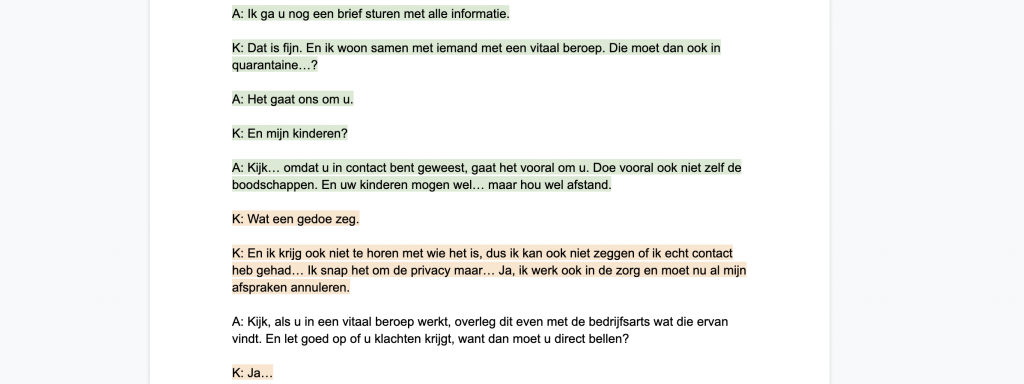

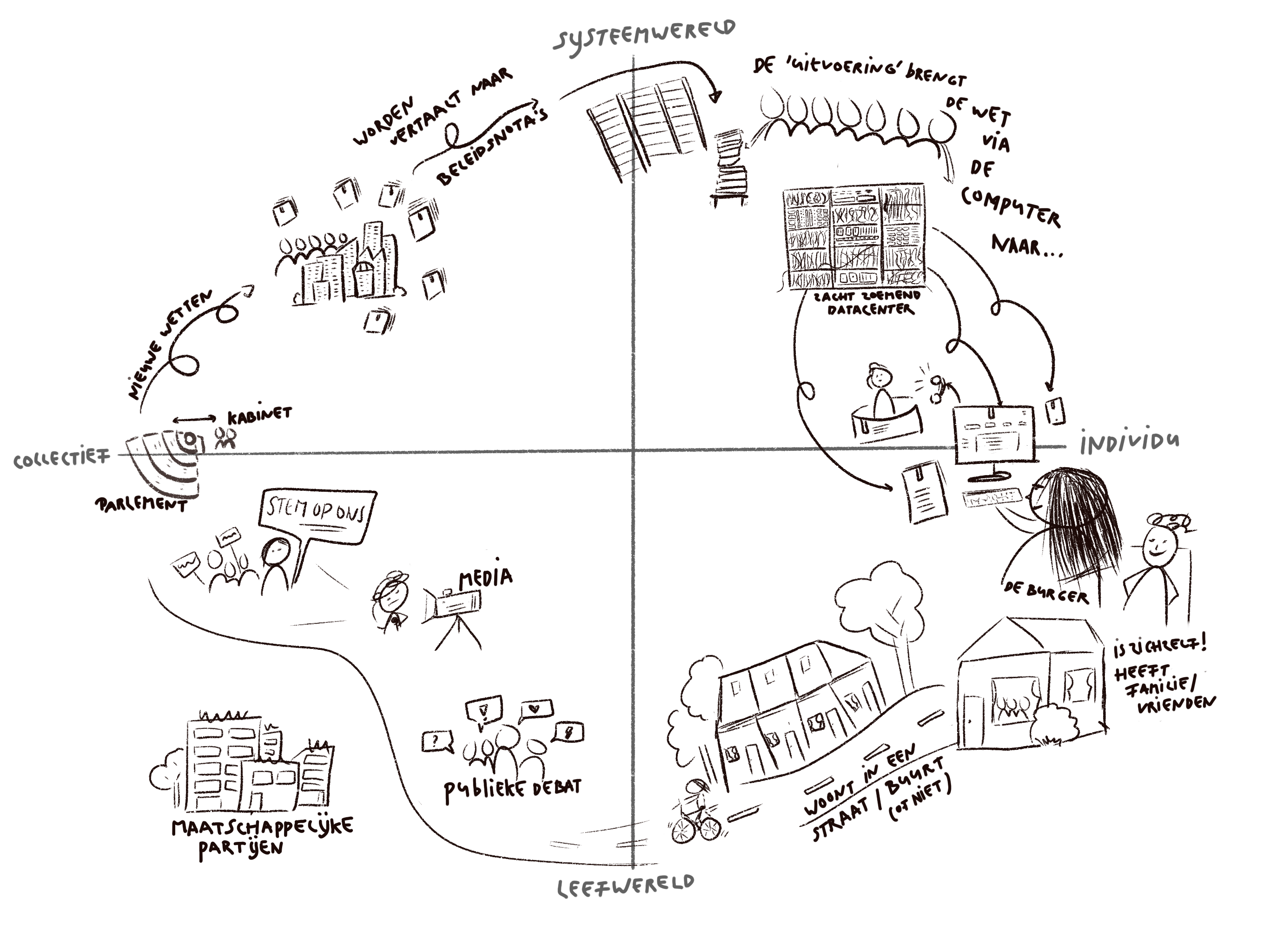

The circle of democracy and service delivery

In my research, I use a division between the system world and the living world, with both a collective and an individual side. This creates 4 quadrants. On the collective side, Cabinet, together with representatives of the people, shape their vision of society. This vision is then translated into laws, policies and services for individuals. Only after interaction between citizens and government does this become a reality in the context of the people themselves, or in the living world. And also in the living world, individuals group together and try to implement their ideas about society, thus coming full circle.

Of this circle, people experience mostly the individual side. “People don’t experience policies, they experience services,” says researcher Sabine Junginger (2016). That means the job of public service providers is to translate collective value into individual experiences that are also valuable.

Want to know more about this collective and individual side? Then read the blog Executive and service provider.

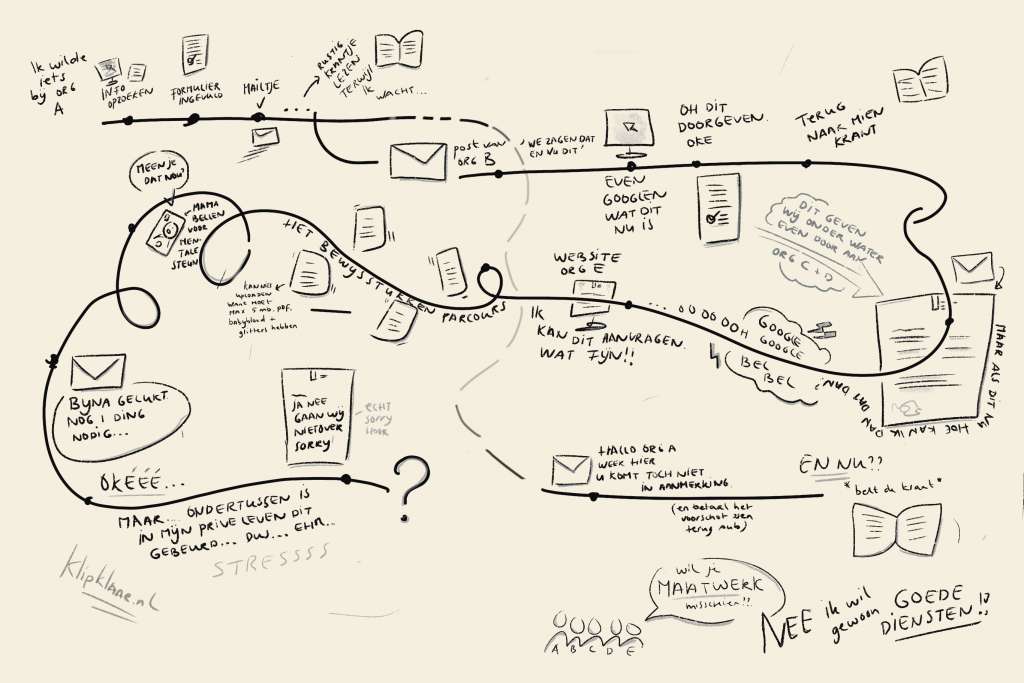

That’s not easy. The practice of the system world now is often a big waterfall. It goes clockwise in a circle, from policy to service and pours out over citizens and society. If you disagree, you can show it in your voting record.

It may be different if we collect citizens’ experiences and introduce them, counterclockwise, into the system world. Those experiences can shape how we offer services and how we design services at all. For the policies enacted for it, and yes, perhaps also for the legislation and associated ideas about interventions in society and the effect it will have.

We have to turn it completely around. And we can, because that’s exactly our job as government researchers.

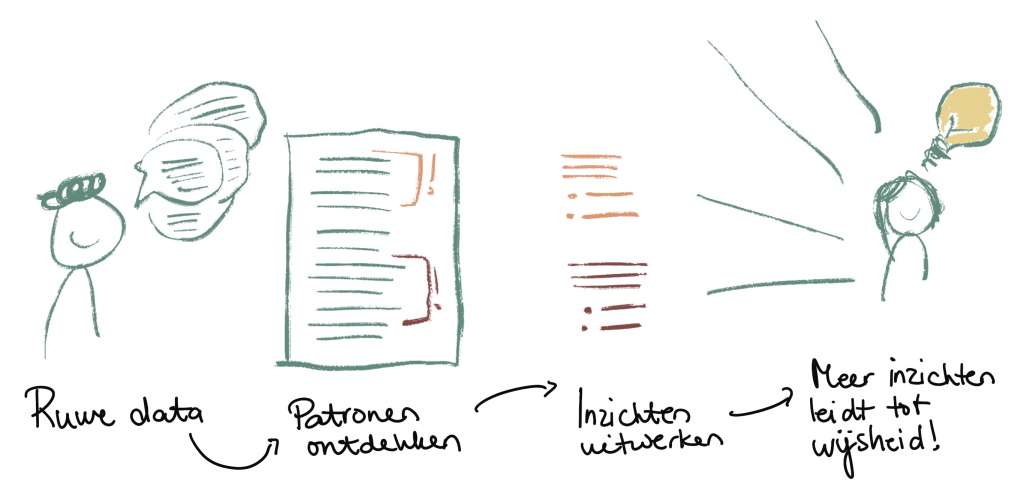

We extract experiences from the lifeworld. We have several methods and techniques to do this properly. Moreover, we are able to share these stories within our organizations in a way that motivates colleagues to take action.

We have shown that over the past 10 years.

How it began

In most organizations, it started with usability testing of websites and other screens. At least for me, too. I started working at the Executive Agency of Education in 2013. One of the first things I learned was how to set up and run a usability test. I visited schools with my laptop under my arm. In the office, I showed videos to colleagues and talked about how students or school employees experienced our digital services.

In 2017, I started my blog. I shared what I was learning and what we were trying out. You also started sending me your experiences.

I saw that we were growing as researchers. We went from testing screens to exploring how to improve all interaction moments with government. We learned new research methods and devised more creative ways to share the insights within our organizations. We took a more holistic approach and also tried to get to know the person behind the user.

We worked smarter. In order to scale up, we started to bundle and archive our insights. We started to get better organized and research positions for that logistics side came up.

And then some of us started getting occasional phone calls from stray policy officials who needed to take make sure people could ‘do’ their policies. “I got your name through, maybe you can help me?” We certainly can.

And so with the insights from the living world, we went deeper and deeper into the system world.

So let’s dream on. Where do we go from here? What do I wish for our field?

More quality

To better understand the whole living world, both the individual as well as the collective side, we need to improve our work. For this, we need more diversity in research roles. The field is so large that no one is good at all the research methods we need. Neither is necessary. In the past, we had research teams consisting of one person doing everything, but that is no longer possible. A good research team includes usability researchers, strategic researchers, customer journey experts, behavioral scientists and more. We must embrace the full range of research methods.

Diversity also says something about who we are ourselves. I still too often see a very homogeneous group when I look around. Especially we, who want to test the bias of the government, must also know our own bias. We have far too few people of color on our teams. One in 5 people has a visible or invisible disability, but looking around now, it seems that everyone has an invisible disability. Our teams are not diverse and that is a problem. As a result, we have too many blind spots that affect how we do our work.

Talking to people

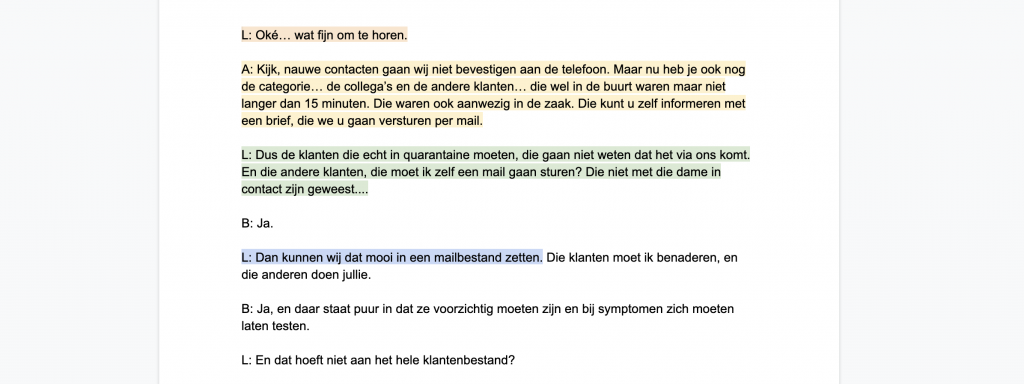

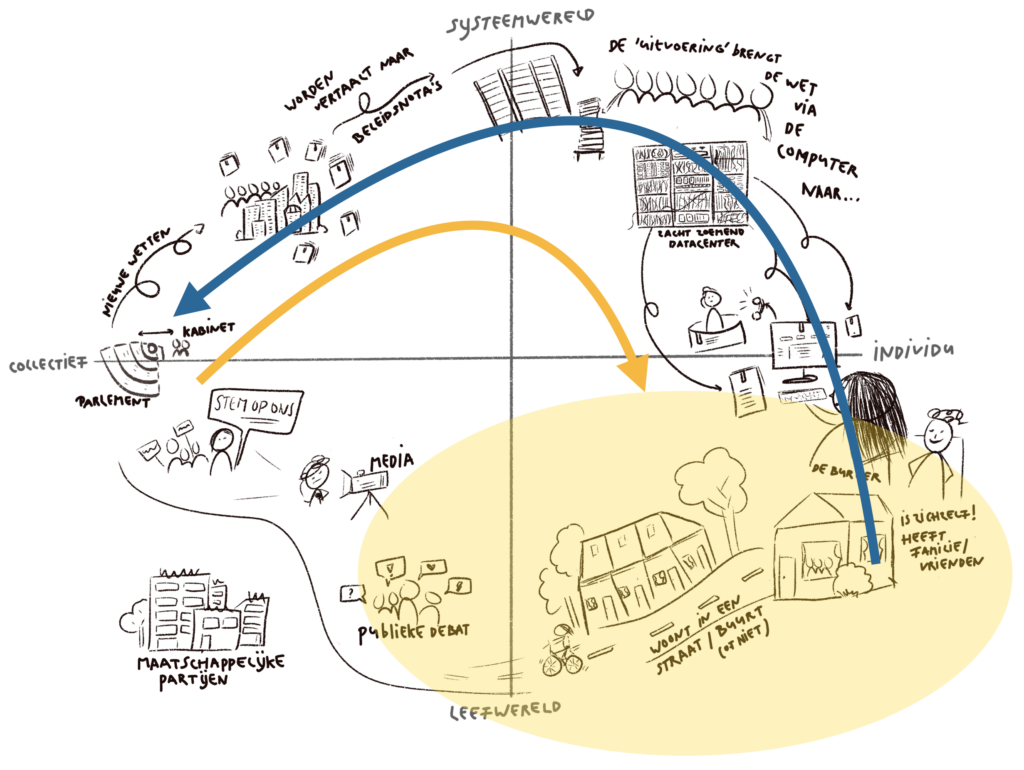

I need to get something off my chest. It really should no longer be a problem to speak to respondents. Really. Come on. This is still far too often a problem in organizations. “Then what are you promising them?” “No, the GDPR.” “It has to be efficient.” Human contact, by definition, is not efficient; indeed, it gets better the less efficient it is. We can only do our job if we are allowed to have real contact with citizens. We shouldn’t put up with this stuff anymore.

Scaling up

If we really want to improve services to citizens, we need to expand our activities. It’s great that more and more development teams want to do usability testing in a sprint, but now imagine if all the teams in your organization wanted to do usability testing in every sprint? How are you going to manage that?

So we need to invest more in the organizational side. Contact with people does not have to be efficient, but we can organize our research work efficiently. This requires a different approach for most of us. The creative and human side is strong among most of us, but now it is time to embrace the blue side we know so well in civic service again as well.

Making policies and services together

I see more and more collaboration between policy and implementation, and research is the basis for that. I hope this becomes standard operating procedure in government. So that policies are based on insights from users and along with the developed services are always tested with citizens.

For this we need to stop that waterfall. I know I am raising a familiar point with this, and that we often complain about it. But we are not helpless on the sidelines. We can help stop the waterfall.

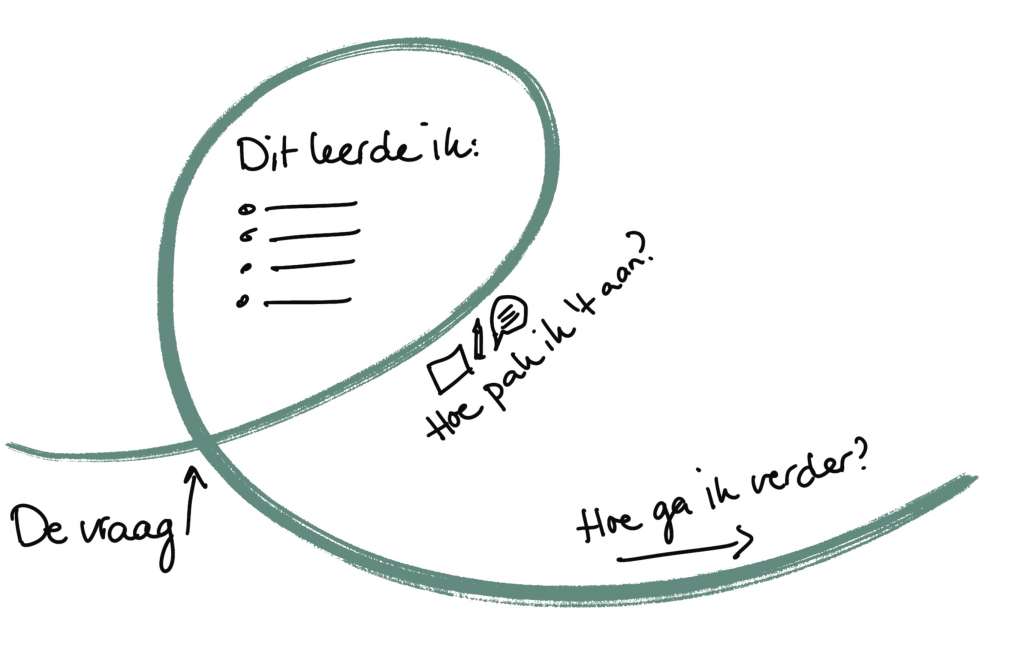

Sharing insights = working in the open

As far as I’m concerned, the best way to stop the waterfall is to share your work. Share citizens’ stories. Share how you do your work and what it brings. Also share the moments when things are not going well. In particular, stories about research insights getting stuck in a cumbersome process or on a system that is already finished help us understand how to work differently.

It often falls short of making a good shareable story as well. We are already so busy. To illustrate, I have spent about 1 day a week for years on this blog and giving and sharing presentations. And even now, on Friday afternoon, I am typing out my presentation from yesterday. I do this because I know it helps our profession move forward. Join me and contribute. After all, I only know what I happen to experience and see in Groningen here. Together we can learn much more.

It’s not real until it’s real

It is great that we are conducting pilots, living labs and experiments. But only when a citizen actually experiences better service, we can get coffee. Therefore, it is not strange to spend as much time sharing your work and following what happens with it as you do the actual research. What good is it if you put in all that effort and then nothing happens with it?

Let us strive to do full circle research. We start with the living world, with the citizen, of course. With the insights, we enter our organization and climb up the waterfall. We can. We work with others to adapt processes and systems, to adjust policies and, if necessary, legislation. We then re-examine how to translate those adjustments into individual experiences.

Full circle research begins and ends in the living world.

When I became a civil servant, my then manager Theo said, “Maike, it’s going to take a very long time for you to change anything in government. But if you succeed, you will have really accomplished something.”

So let’s start continue.

Continue reading?

This blog is full of tips on how to research and get your organization on board. For example:

- Why we need standard good services more than customization.

- How to properly document and thus share your research.

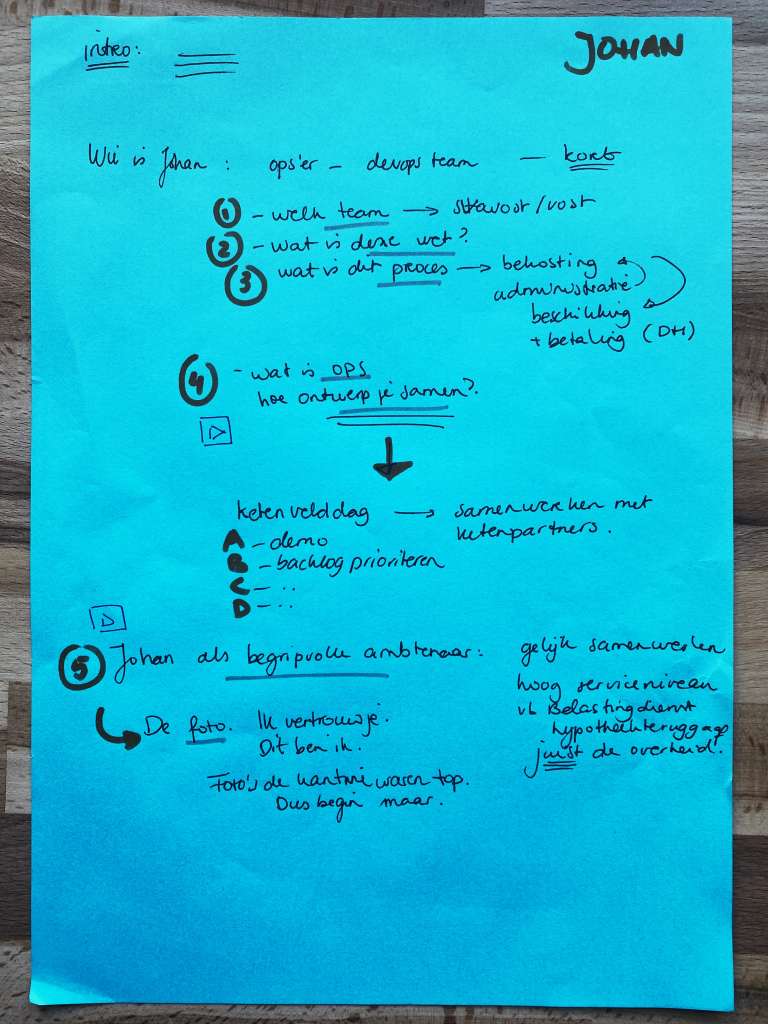

- How we at DUO examined our own bias with photography.

- Four ways to tell stories in your organization.