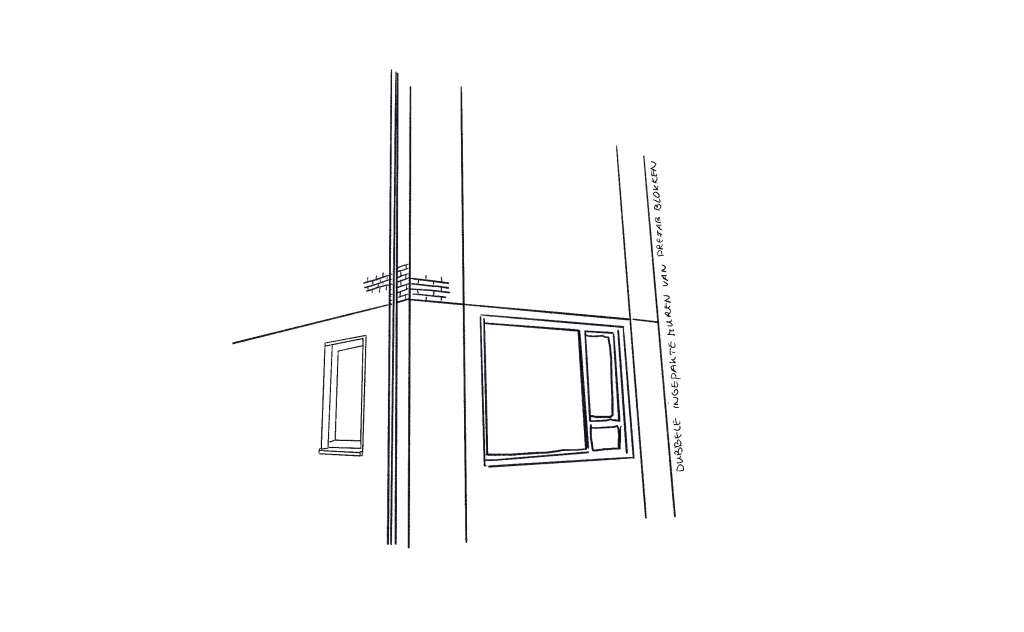

The first time I saw struts on a house was years ago when I went to lunch with Fiora, a colleague. In the middle of her kitchen were four struts. The kitchen table fit right in between. A chair on all sides, you could walk around it and it would be full. It was an idyllic little house next to the church in Huizinge. We ate a cheese sandwich and we didn’t necessarily talk about it. This is Groningen.

Fioor now lives with her girlfriend Wieneke in Bedum and she is no longer a colleague but a friend. Two months ago I was there with Jasper, another kitchen table, this time with gin tonic. “I got the job,” I cheered. “What does the National Ombudsman actually do?” asked Wieneke.

I explained. “If you can’t work it out with the government, you can come to us. We deal with your complaint and we help the government learn from it. So we also do broader research, and especially with the latter I’m going to work on.” I hadn’t finished talking or Wieneke slapped her hand on the table. “Well, I do have another complaint for you then.”

I knew they were remodeling. The front facade and living room had been impassable for weeks. In the winter, I had enjoyed bobbing along in the rented hot tub to break the grind of sitting in the kitchen every day. I knew they had earthquake damage. But they had discovered new damage during the renovation, even quite large ones, and had to stop the job halfway through, call the IMG again, wait, hesitate, go ahead with the job, or not, or do, with the risk that it would have to be reopened later anyway. So they were back in the kitchen, in that kitchen for months, and still went ahead with the renovation but tried to not get too attached to that beautiful color on the wall because it might have to be redone later. Fuss, fuss, fuss.

“And now that it’s almost finished,” I asked, “what are you going to do with the outside?” “Yeah, what else can you do,” said Fioor. “Stuccoing, sealing? It won’t look great anymore anyway.” You can really only put a band-aid on it; you won’t get your beautiful stones back.

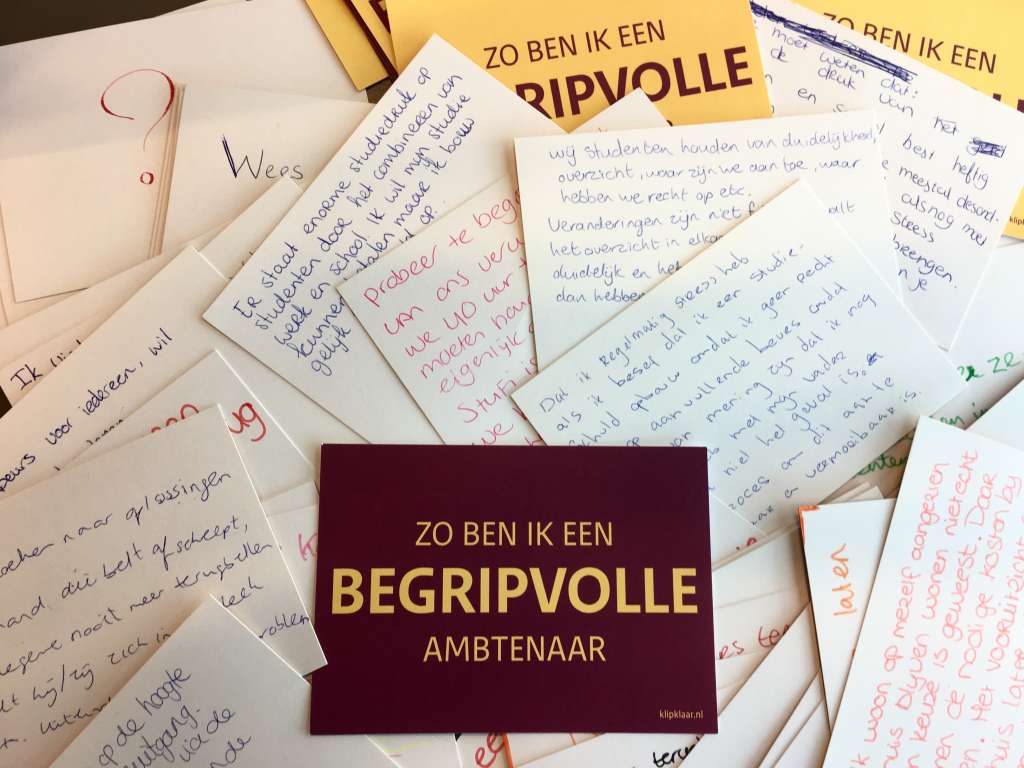

I have now been on the job for 4 weeks as project leader for Liveability at the National Ombudsman. The subject of livability includes, for example, the research we are doing on the environmental law, energy transition and also the gas mining damage and earthquakes in Groningen and its surroundings. How does the government treat its citizens? Does she do that properly?

Last week, my colleagues and I were in Groningen for three days talking to residents with damage, seeing how the strengthening of houses was going, and speaking to all kinds of agencies and hearing their side of things. Colleagues slept in Appingedam, I slept in my own bed in the city of Groningen. By car, I drove back and forth, several times a day on the N360. From Appingedam to Garmerwolde, to Kantens, through Loppersum, ‘t Zandt and back towards Delfzijl.

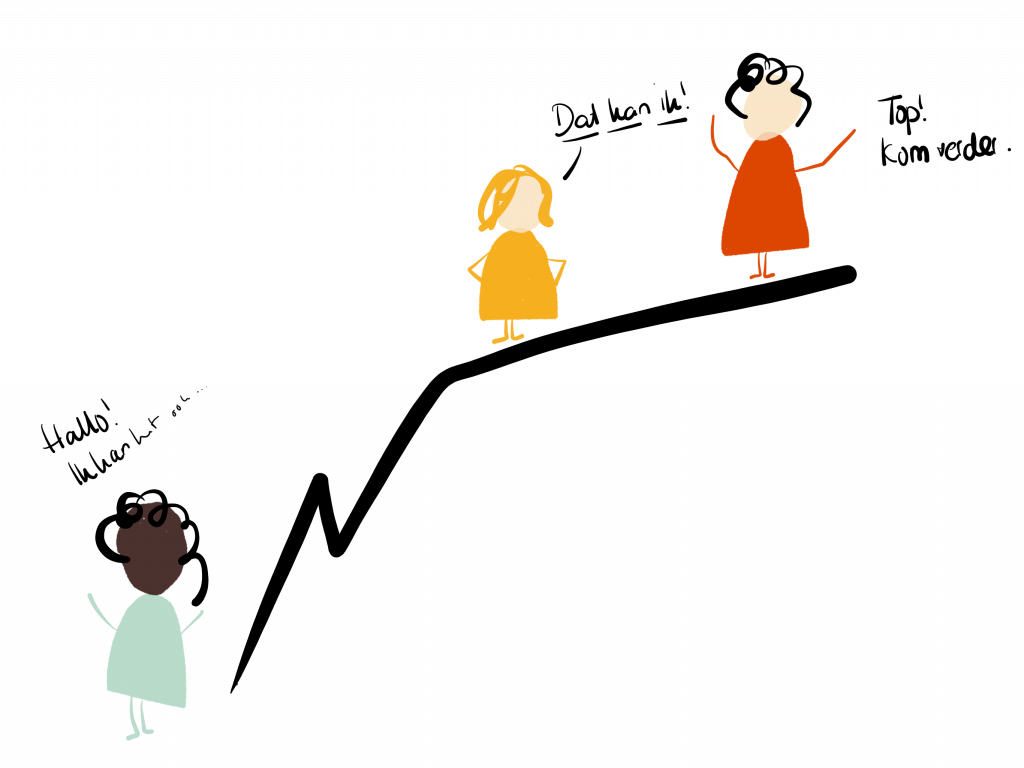

In Appingedam, a lady told of her difficult objection process at the IMG. In Kantens, we were given a tour by a couple. Hop, into the car, through the village. Past their old house that was now a lawn, the neighbors still had no reinforcement advice. Through Centerparcs, as they called the temporary change houses on the outskirts of the village, toward their “new” farmhouse where, on top of the pile of bricks that was their kitchen, they told how it should be again.

Next day a tour of ‘t Zandt where the entire village is reinforced. From the main street, we walked along de Molenweg. While the right side of the street had already received a letter for reinforcement, the left side still knew nothing. In the neighborhood app, it went back and forth. What is going on? The further we walked the more the village turned into a construction site around us.

In the evening back home, for once I didn’t take the N360 but drove back via the Graauwedijk and the Rijksweg. Roadways that I normally love to take when I take my inflatable canoe out to boat somewhere in the province. I ride here so often, I paddle between these villages. I have been reading about the earthquakes and following the news for years. I myself have some damage to my home in the city.

But with my urban eyes, I had not seen that it was like this. I did not see what the couple from Kantens was pointing out from their car. What it is really like to live among struts and cracks.