The sun was shining, I was in one of my favorite cities (Maastricht) and had breakfast with Limburg pie every morning. Last week was Frontiers in Service 2023. My first academic conference. Four days, with a day especially for PhD candidates, dedicated to the most current research on services.

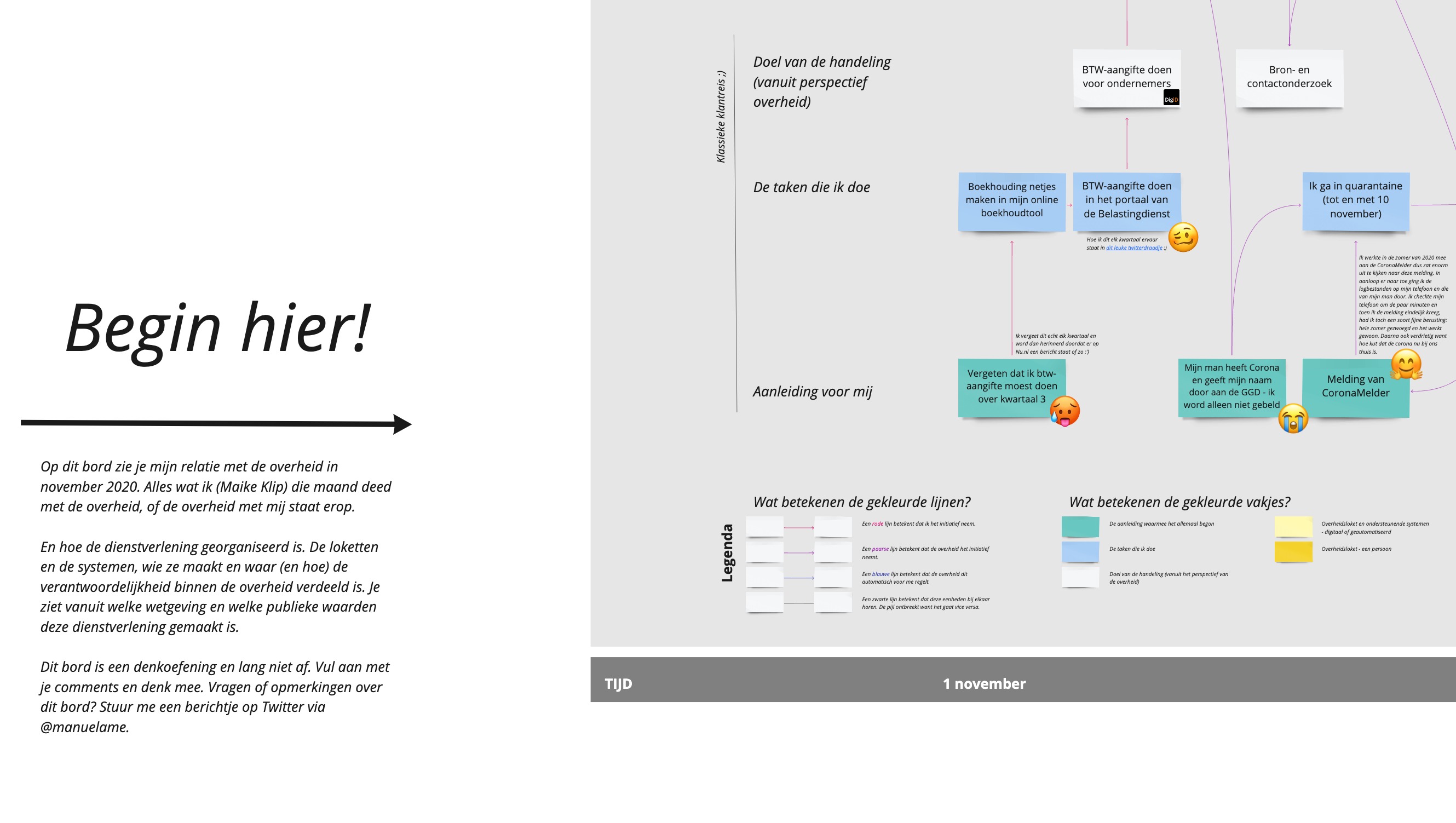

In this blog, I share what I learned from this conference for my own research on public services that are good for people, in my case study on Dutch national public service providers. I do so in the form of 4 reasons why it is a smart idea as a beginning researcher to attend conferences right from the start of your PhD.

Reason 1: get a good overview quickly

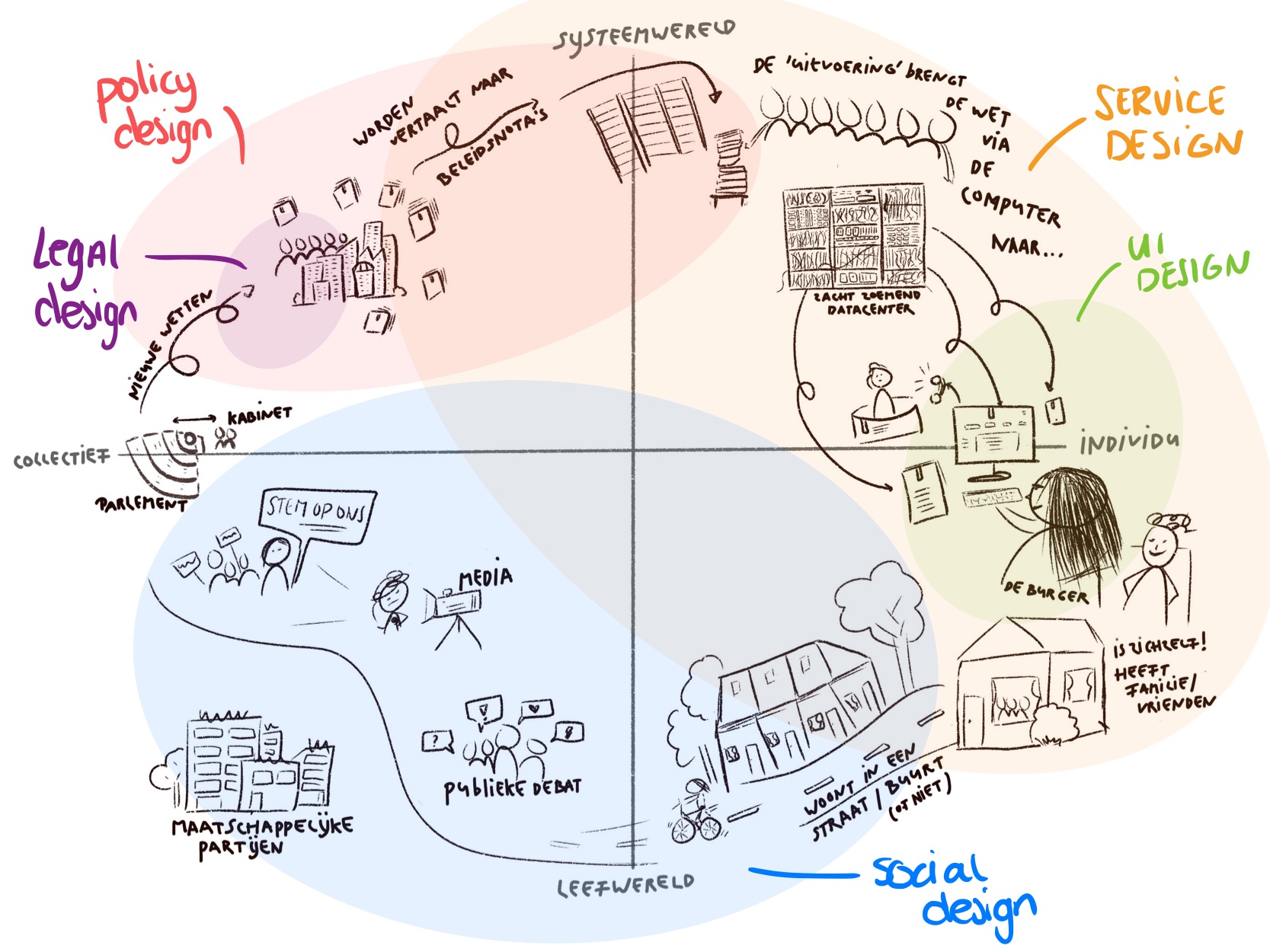

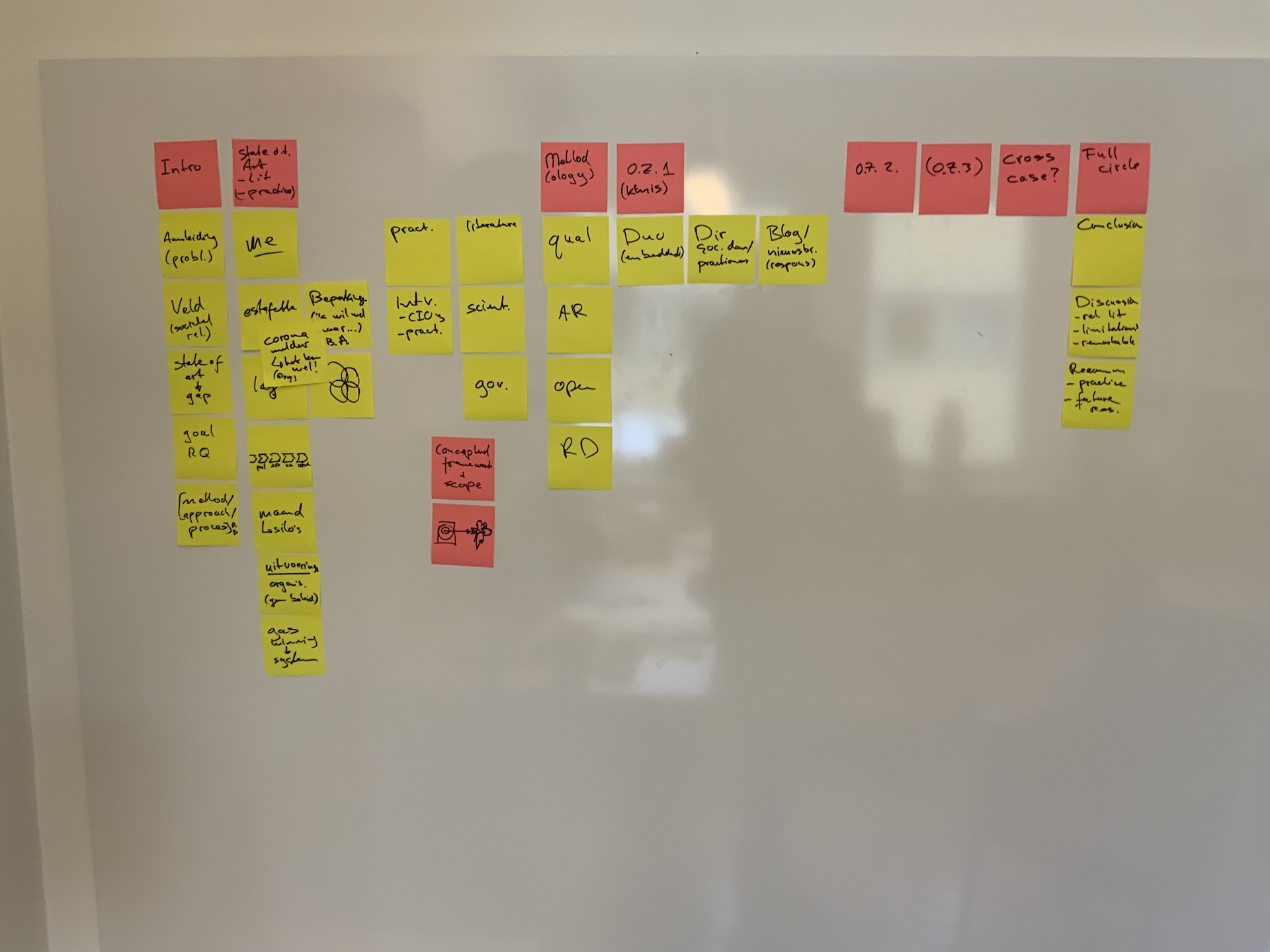

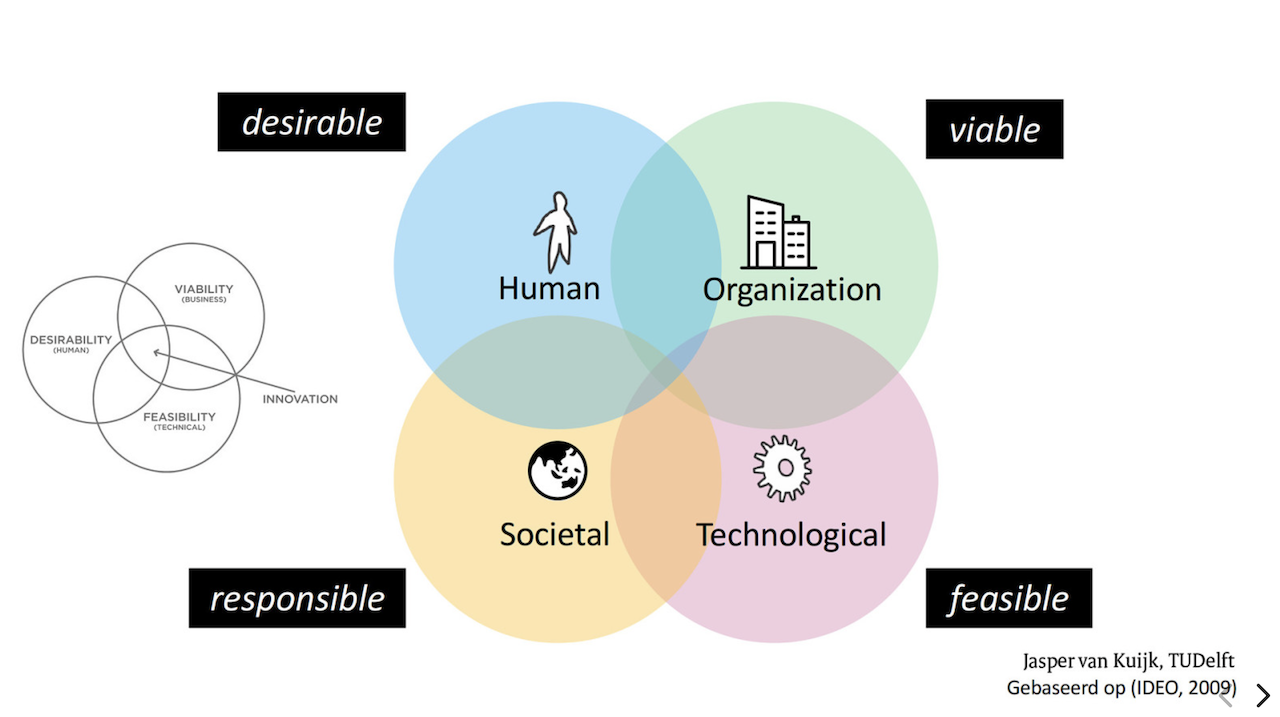

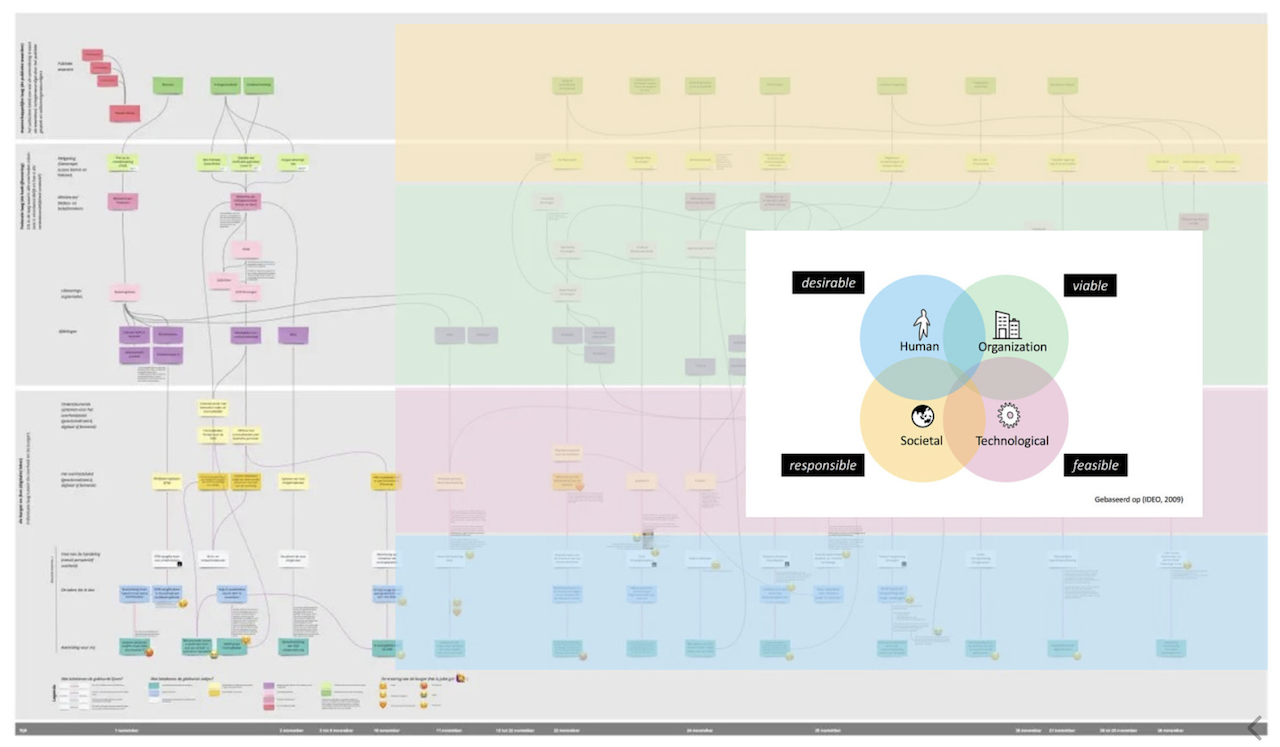

The service field is actually not my own domain. I do research from the Technical University of Delft, Industrial Design Engineering. Design is my home base, and I do research on how to design services in government. My research connects three disciplines: design, services and public administration. To fully understand the services part, I went to Frontiers and regularly visit CTF, Karlstad University’s service research center. (I wrote this blog about my first visit at CTF.)

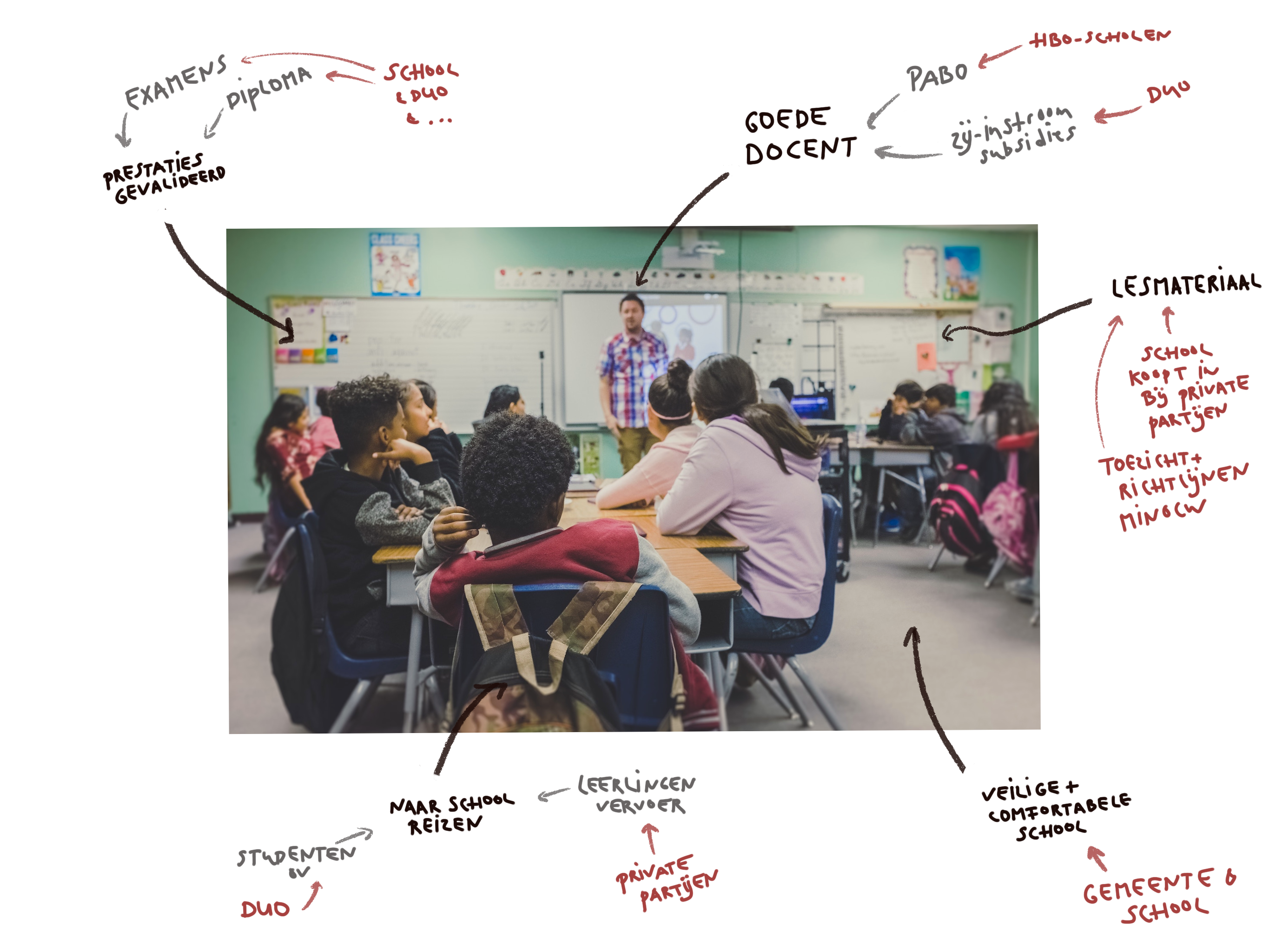

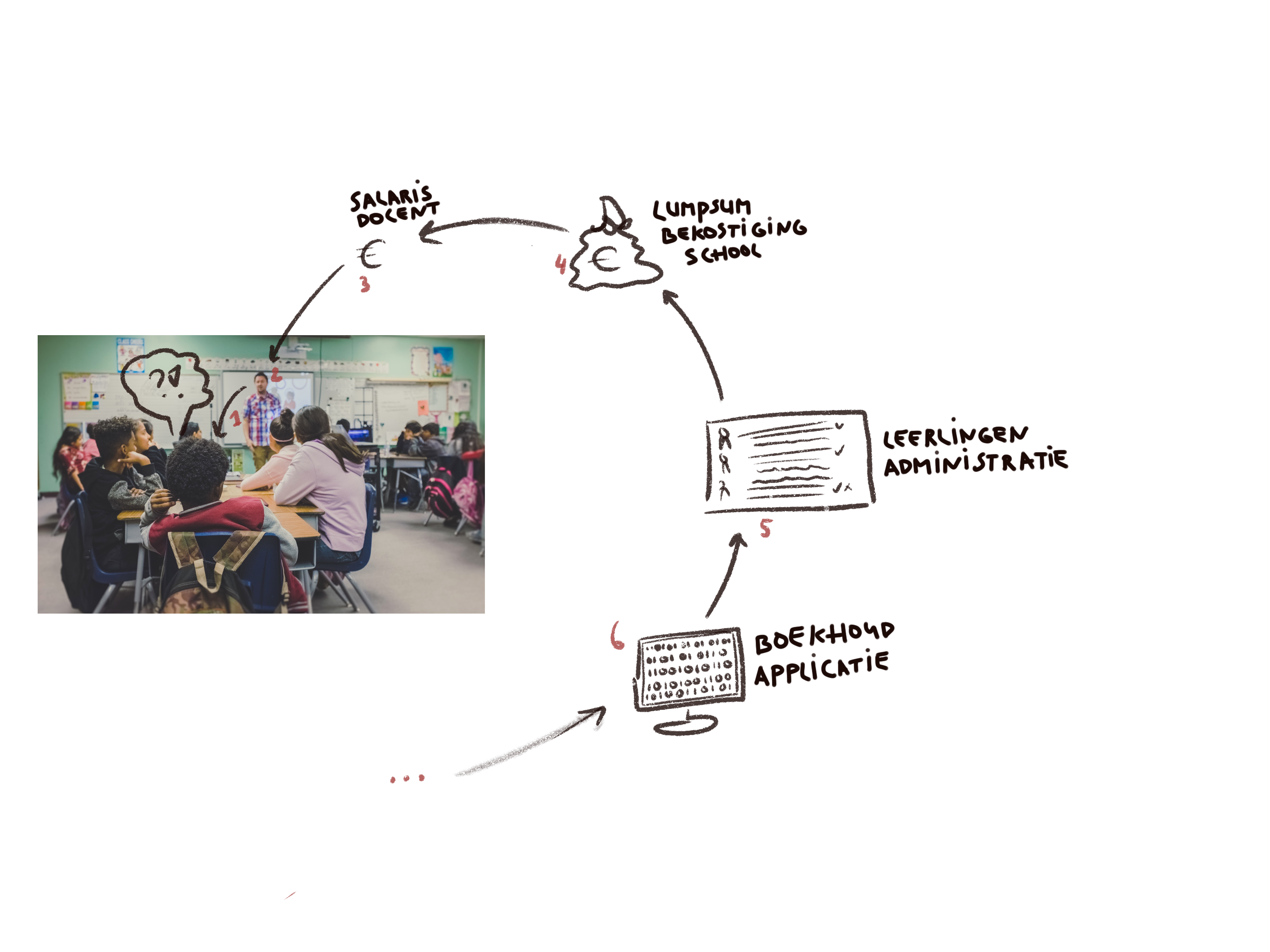

Through conversations at CTF, I stumbled into the service field. From there I looked for a route like a snowball finding its way. Of course, I read the classics, for example, on service-dominant logic. I practiced how to apply this way of thinking in my research context by writing the blog the value is in the classroom.

A conference highlights the most current state of a research field. One look at the program and you see how much there is. The services field is much larger than I thought!

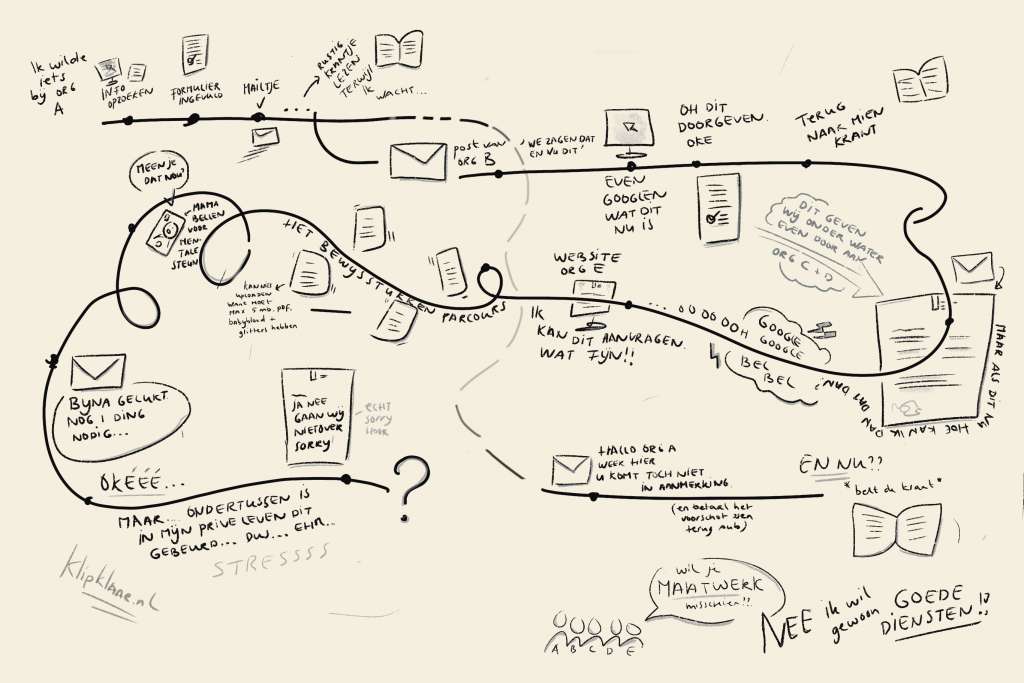

I found out that public services are a niche here, and government services may be the niche within the niche.

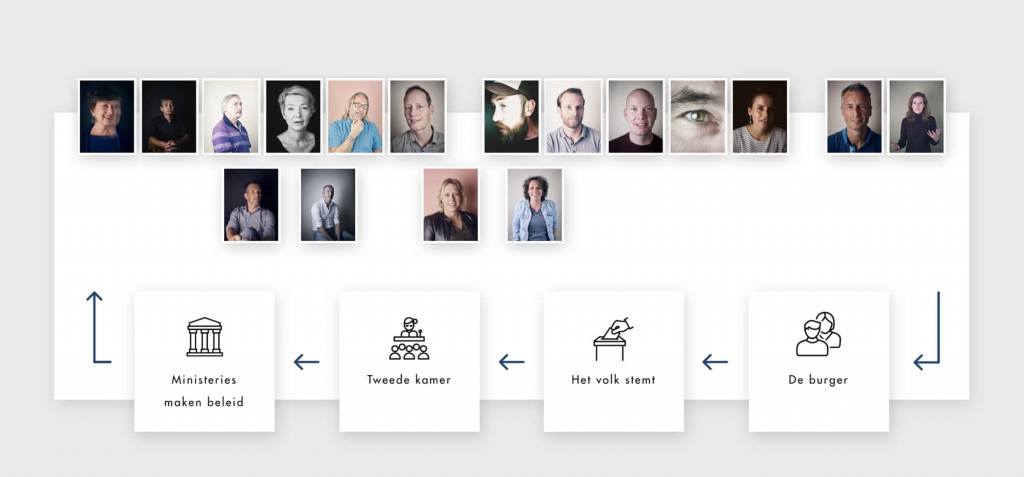

Frontiers in service is a conference that deals with services, including the creation and delivery of services in the broadest sense. The keynotes focused on the child care benefit scandal in the Netherlands and Starbucks’ new service concepts in Asia. We saw experimental examples of VR glasses in education and service robots in healthcare. Nearly 250 studies were presented in 60 sub-sessions. View the entire program here.

I discovered that “transformative service research” is very hot right now and, as a separate research topic, even has its own acronym: TSR. From my own reading nook, I had not yet come across this. This is something I will be looking up more about in the near future.

Reason 2: free advice

If at the beginning you still nervously walk with your coffee to a table where no one is standing, by the end of the conference you know that you can join a busy table. Indeed, that is a very good idea. After your name and your university, you drop that you have only just started your PhD and it immediately starts raining tips from the seniors at the table. They ask questions, talk about their own early days and give advice on writing good articles for top journals. That they sometimes contradict each other we will never let them know of course.

This free advice makes sense because the purpose of a conference is to exchange knowledge. Everyone seeks each other out and talks about each other’s research. Rarely have I received such good (and critical) questions about my research: what I want to contribute to it, how I want to approach it and more.

In line for the ice cream truck, for example, I was engaged in a discussion about what public value is with Jakob Trischler (whose articles I have read before). Is that really well defined yet (we thought not) and does public value actually have a place within the marketing-dominated world of service research? I’ll have vanilla with raspberry in a cone, please.

Extra helpful was the advice of Mike Brady, Professor of Marketing at Florida State University and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Service Research (JSR). In a small ask-me-anything session, he talked at length about JSR’s editorial process and how to write and submit your first articles to top journals as a young researcher. Those were a lot of useful tips.

Reason 3: practice pitching and learn from others

Most people gave presentations themselves; I was there as a consumer. If my paper will be accepted, I may present at a design conference this fall. During Frontiers, I was able to watch how others show their work. What are the codes, the unwritten rules? How do others structure their presentation? How do they deal with critical questions?

Yet I could not consume alone.

Regularly, someone asked what my research is about. I am now over six months in and exactly at that stage when you start doubting everything. My rehearsed pitch “I’m doing research on how to design government services that are good for people” is starting to come out slicker and slicker, but by now I’m having doubts about the definition of government services, about what is design, what is good and what are people really??!

That’s okay. By telling what you do and why it is relevant over and over again, you learn to put it into words better and better. After the fifth pitch (and because of the questions I received), I subconsciously adjusted the pitch a bit. By the fourth day, the insecurity was gone and I surprised myself how much better I could explain what I want to do.

I am still on “how to make government services that are good for people” haha. But also on how important it is to properly define that “public value. Maybe I can do that by just delving more into the public administrative side: the principles of good governance and the Rule of Law of course! The radars are already turning at full speed again.

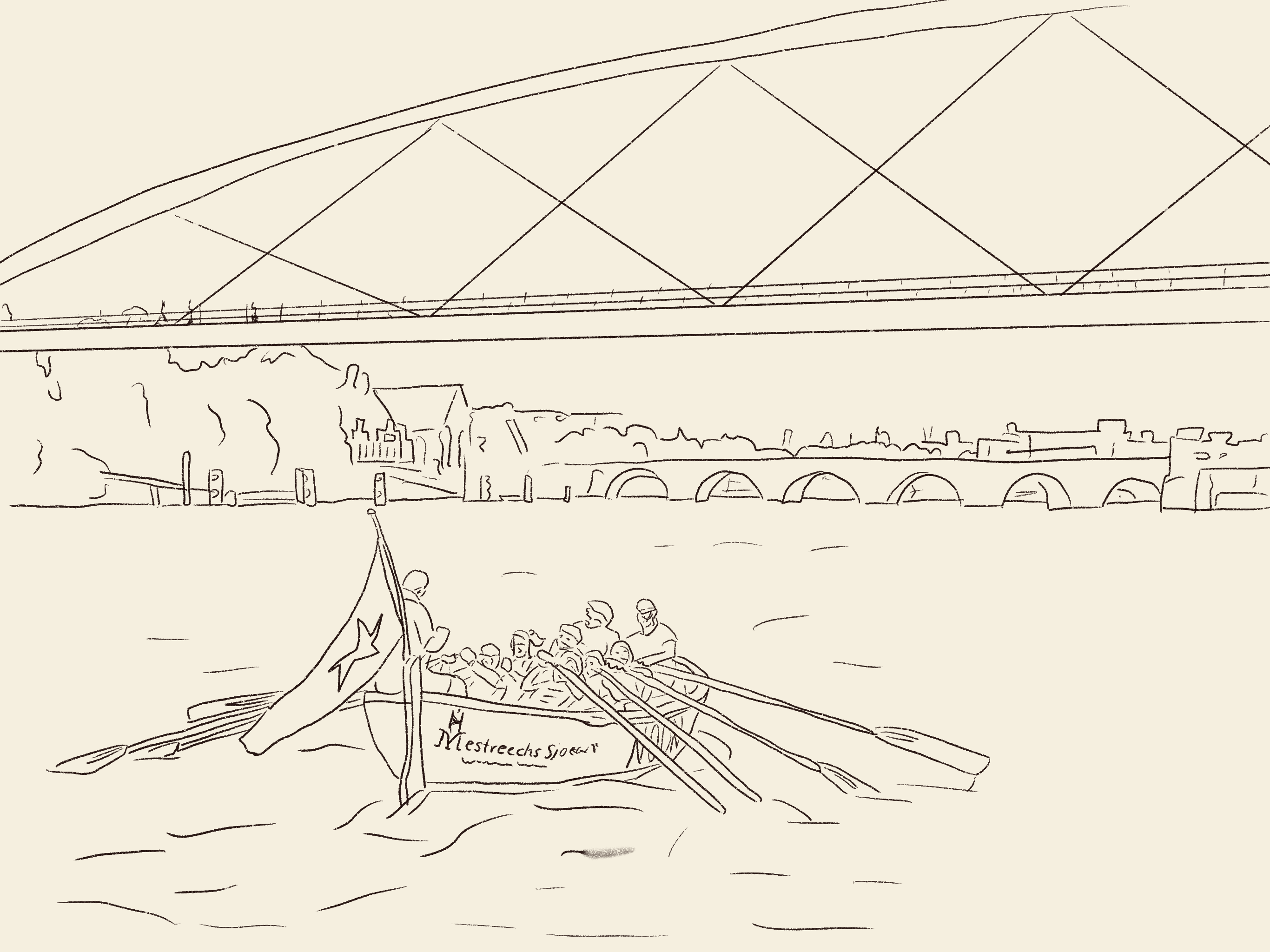

Reason 4: meet nice people in a new city

As an external PhD candidate, I am not at the university much. I live in Groningen, which is 3+ hours by train to Delft. My supervisors live in Delft and Karlstad, so most of my research happens online, from home or from my research context, in the Dutch government. I don’t know that many other PhD candidates to exchange experiences and joke around with. However, this can be done at a conference (Della and Mike, I see you), especially if a special Doctoral Consortium for PhD candidates is organized.

Maastricht is a super fun city is and the University of Maastricht knows how to organize a cool conference. Attending a multi-day conference is also getting away from the grind, from behind your desk, and getting new inspiration. Rent a bike, have breakfast on a terrace, take your new friends into town. I even got to row on the Maas River with the Maastricht rowing team.

In short: many new experiences bring new questions to delve into in the coming time. The next conference will hopefully be IASDR2023 in October. But first, in August, I am going to CTF in Sweden again :).

Want to follow my research on Dutch government services? You can! Through my newsletter (in Dutch) or follow this blog via my Linkedin.

References and reading tips

Koskela-Huotari, K., Svärd, K., Williams, H., Trischler, J., & Wikström, F. (2023). Drivers and Hinderers of (Un) Sustainable Service: A Systems View. Journal of Service Research, 10946705231176071.

Jakob Trischler & Jessica Westman Trischler (2022). Design for experience – a public service design approach in the age of digitalization. Public Management Review, 24:8, 1251-1270.

This page lists all the books and articles I use in my research.