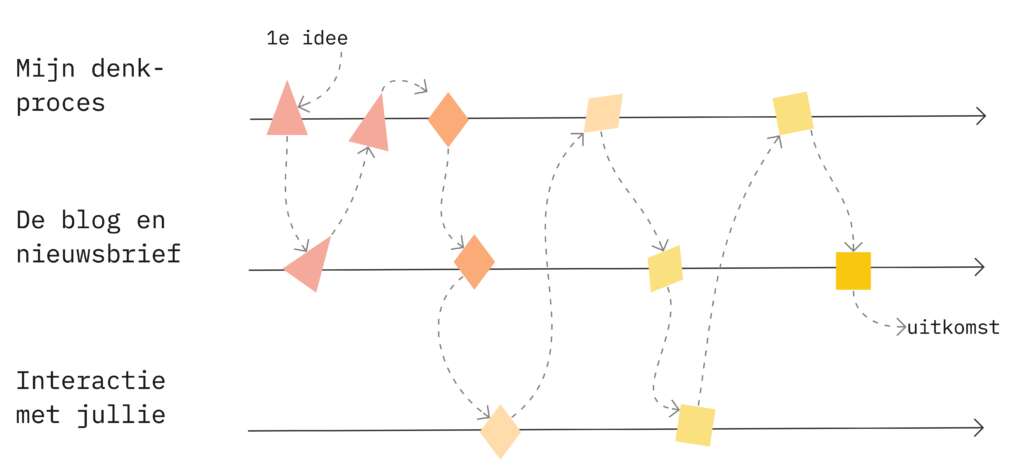

When you want to create government services that people can use to achieve their goals, it is important to design them human-centered from the beginning. You do this by continuously involving users during the conception and creation of services. In a series of blogs, I explore the principles of human-centered design. Involving citizens continuously is the third principle.

Want an update in your mailbox every month about my research? Then subscribe to my newsletter.

Calculation tools for students

Ten years ago, I started as a junior researcher at DUO. I researched how students were preparing for the new loan system and what digital services could help them do so. I helped create these calculation tools. This was my first project where I learned how to engage your target audience when you create something.

By interviewing students in their senior year, I learned that they needed not only a button to apply for student loans, but also an explanation of what stufi entails and help understanding their financial situation for this new phase of life. With laptop under our arms, we went back to a high school again to validate the first sketches and later clickable prototypes with young people. Could they use these tools and did it help them achieve their goals? Did it help them prepare for student loans and make good loan choices?

A year later, I started this blog and shared the lessons I learned in doing this kind of usage research. The archives in this blog are full of them:

- For example, how to use card sorting to test navigation on your website.

- Or how I signed myself up for a neighborhood supper club to connect with people who are required to integrate.

- And 20 creative ways to find the right users so you can do interviews or tests with them.

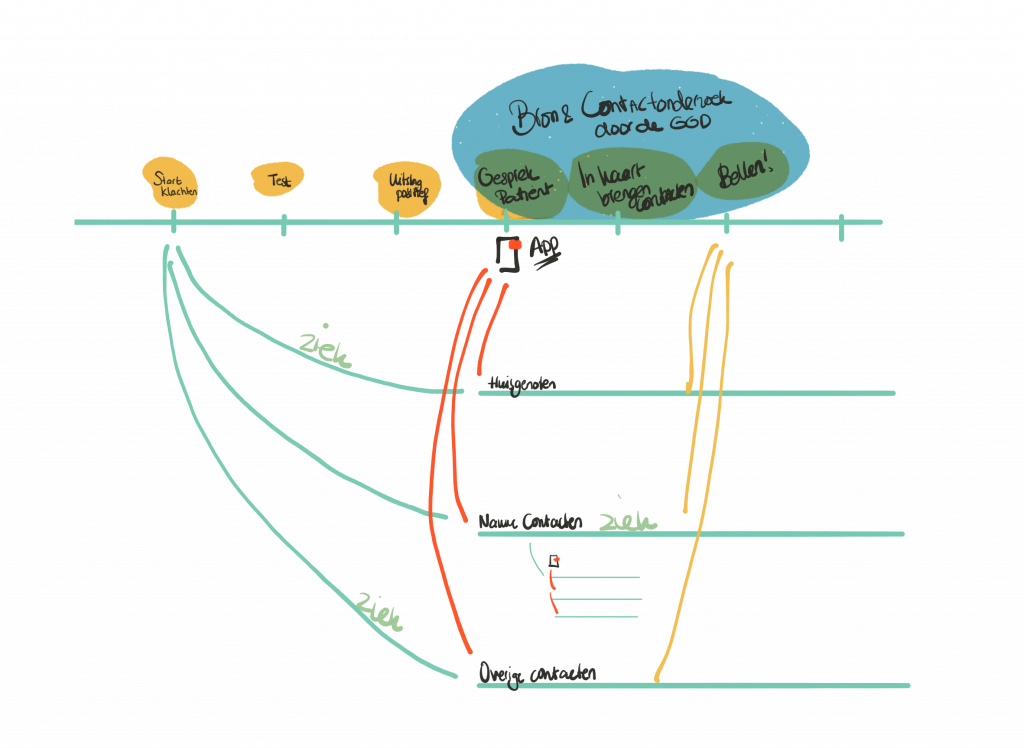

- How we tested the CoronaMelder app simultaneously with users in Amsterdam and GGD staff in Utrecht.

You are not the user

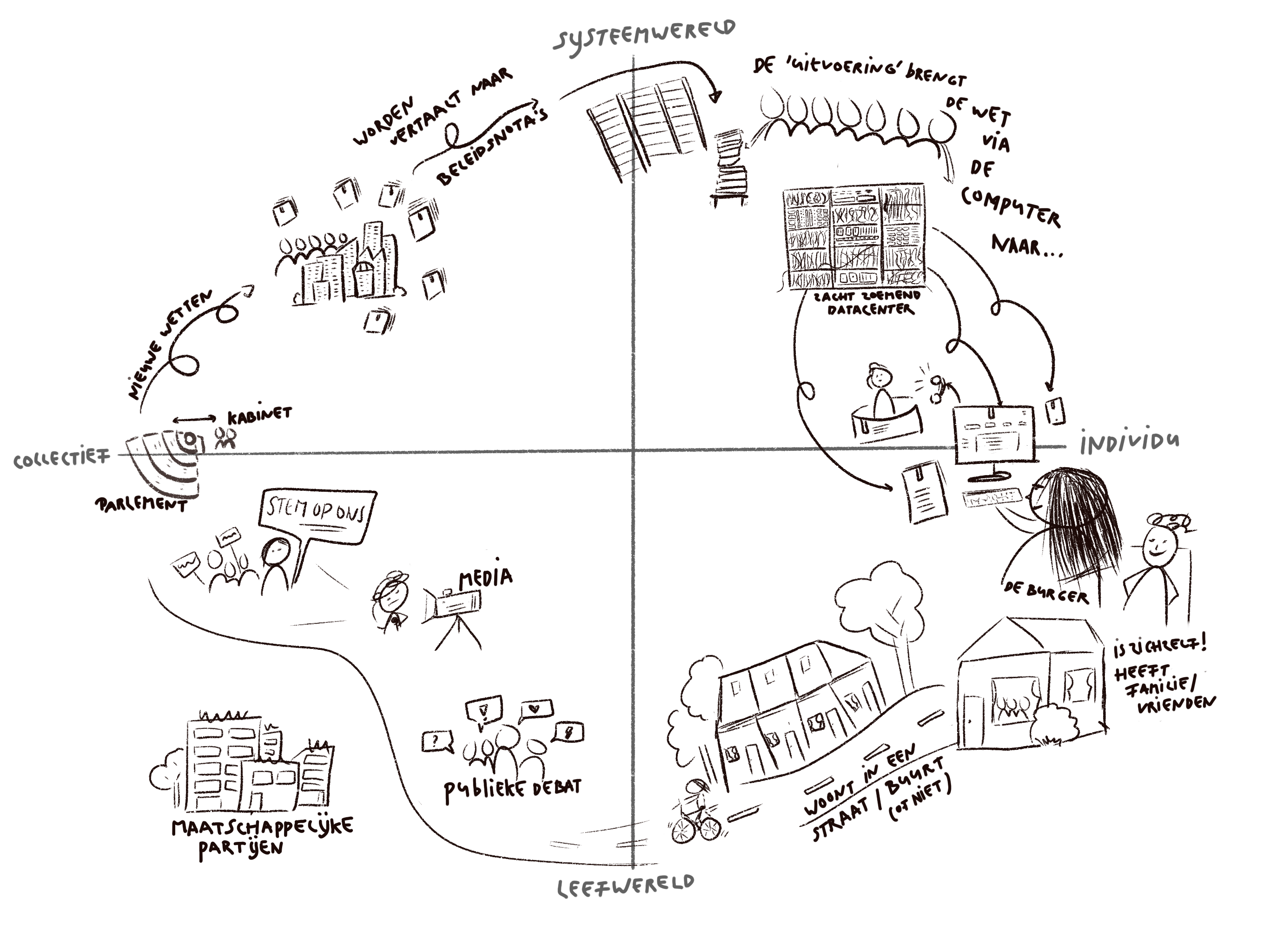

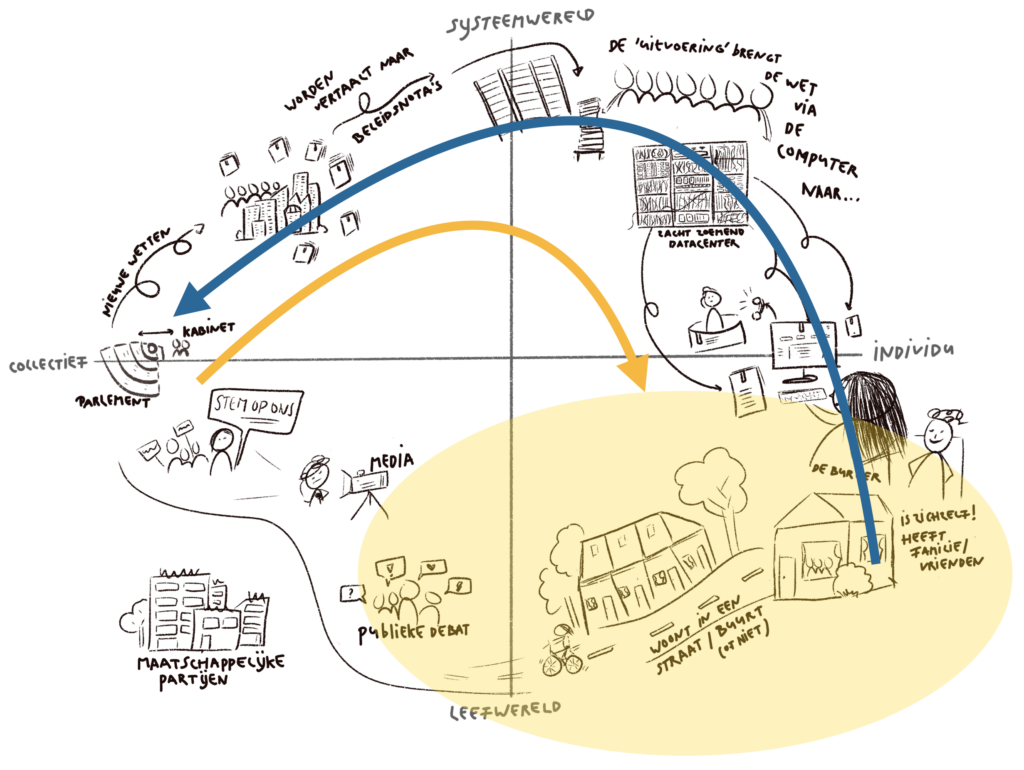

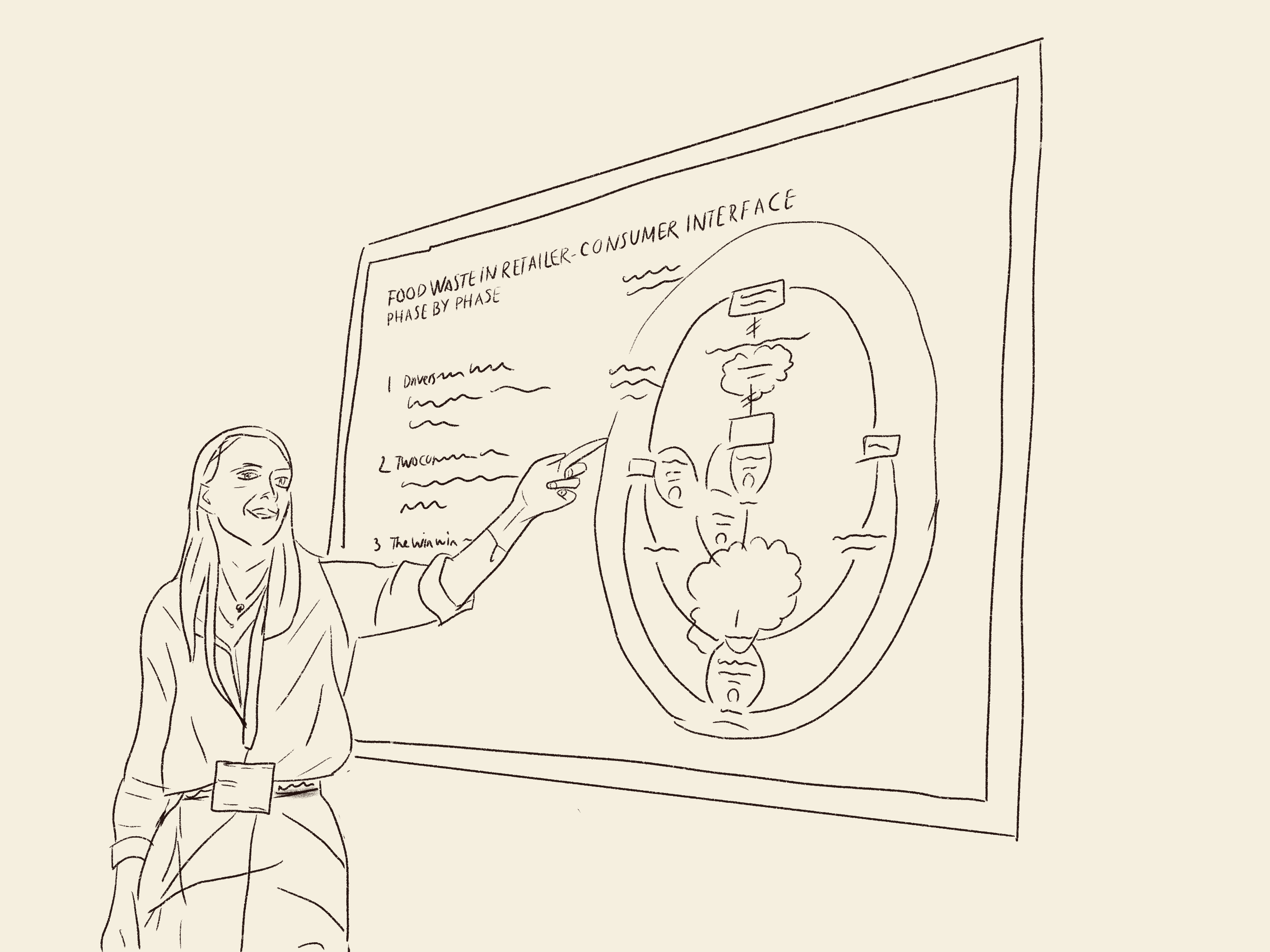

The ISO standard on human-centered design calls the continuous involvement of users one of the important principles for making human-centered services. Precisely in order to fulfill other important principles such as understanding your users and starting from their whole experience, you must seek them out and involve them in your creation process.

It is often said, “But we are also users,” or “we are also citizens.” To some extent, this is true. But … as creators of digital public services, there is still a gap between us and the users.

Just as many people have a “guy” for their car, in my family I am the person to whom all questions around bureaucracy are asked, even about government organizations where I have never worked. “You ‘get’ government,” my mother-in-law would say. That’s right. The (im)logic of forms, the different counters, how to disagree with a decision and what to do then. I know the way or can easily find it. This well-known phenomenon is called the designer-user gap.

Makers, which in this case are the lawyers, designers, developers and all other colleagues involved in making services, and they:

- Know too much. They know the policies and little rules well and are familiar with the internal processes.

- Can do too much. They know where all the buttons are on the website because they created them themselves. They know how to fill out forms because they formulated the questions themselves.

- Are too attached to the service or product. They have made their own design choices and have their reasons for doing so. You are proud of your work, and you want to defend this.

That’s why you need to involve real users. They don’t know the policy (yet), and otherwise probably not in as much detail as you do. They are not experts in your website or form, nor are they attached to the choices you have made. They just want to use your service to achieve their goal. Whether that succeeds is the ultimate test. You yourself are not representative enough to judge that.

By engaging your target audience, you are directly at one of the most valuable sources of knowledge about the use of your product or service. A service becomes more effective the better the creators and users work together, according to the ISO standard.

Risk management

Working with users is useful to avoid major mistakes. When people can’t use your service or product when they should, it creates all sorts of additional problems. This is especially true in government, where users cannot switch to competitors.

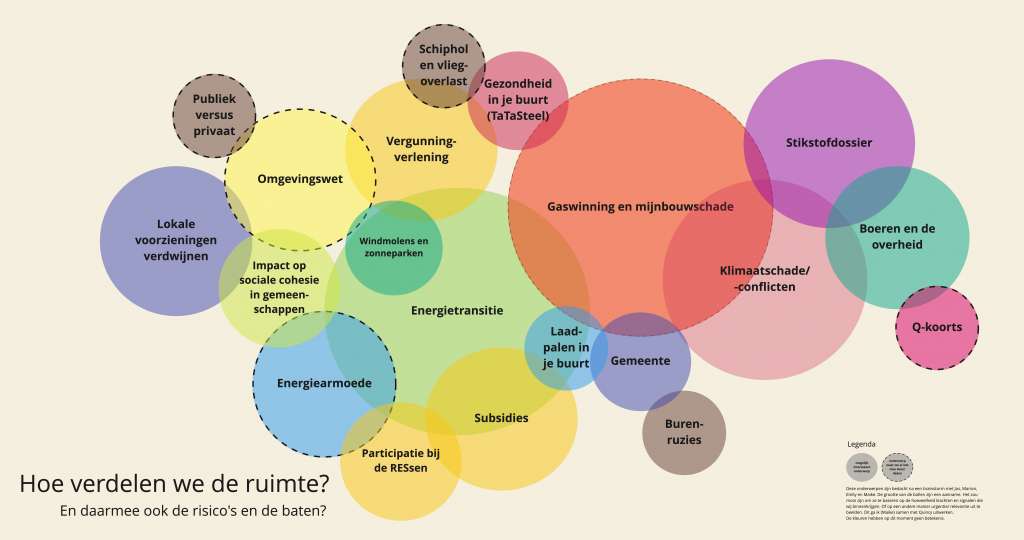

For example, people get extra stress and have to figure out and do extra things. For example, in Groningen for people with earthquake damage where it is regularly a Billy bureaucracy.

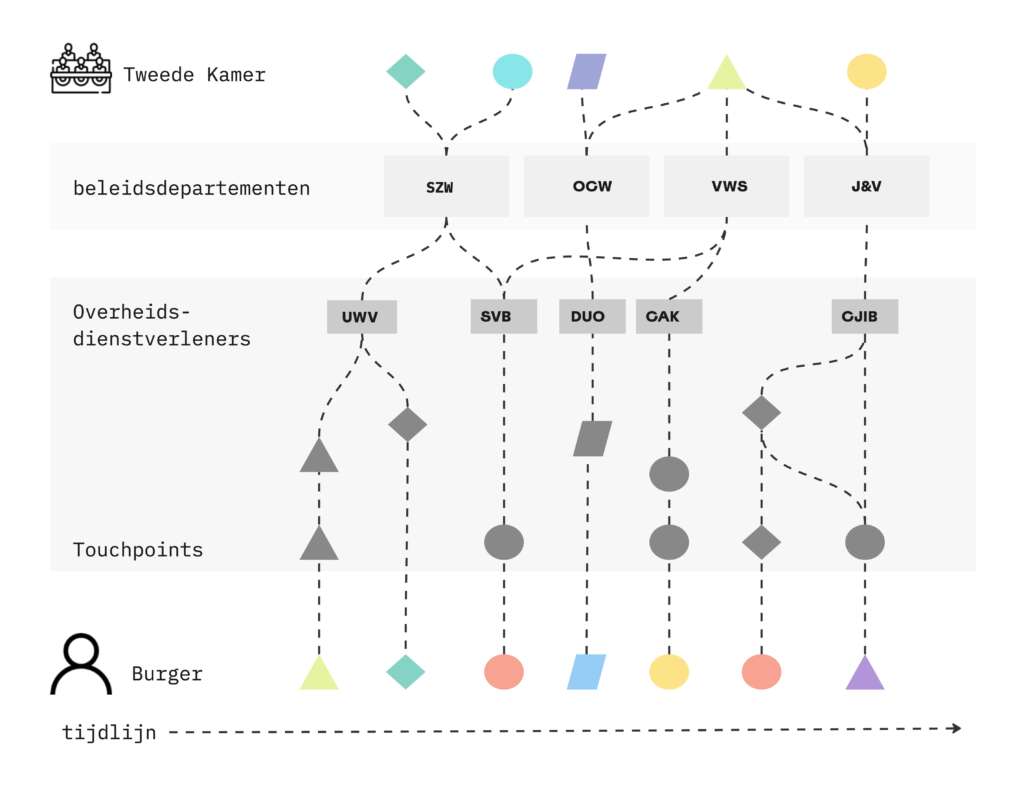

Costs can move unnoticed. When the loan system was introduced, DUO warned in advance that the student loan system was going to be very challenging to implement. Because there were more and more “cohorts,” it became very difficult to explain on the website and you noticed that later on in the questions asked on the phone.

Because during corona it was not always possible for the elderly to go to the ballot box themselves, the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations thought of allowing them to vote by letter. Only this was not properly tested beforehand, so many well-intentioned votes were rejected in the counting process. In total, this saved almost one chamber seat!

In addition to potential stress for citizens and inefficiency for organizations, not collaborating with your target audience can also lead to failure to achieve the societal goals we want policy to achieve, or even exacerbate problems. See, suddenly it’s no longer a soft story to engage users, but a way to manage risk. And we love that in government!

How do you begin?

Start by approaching representative users. Make sure the experiencers you work with have the abilities, characteristics and experiences that are representative of your future users. At CoronaMelder, for example, I worked very specifically with language ambassadors who could explain to me exactly what medical terms or phrases they did not understand, and probably a lot of other people who had trouble reading as well. For finding the right respondents for usage research, there are also many good agencies with a large network.

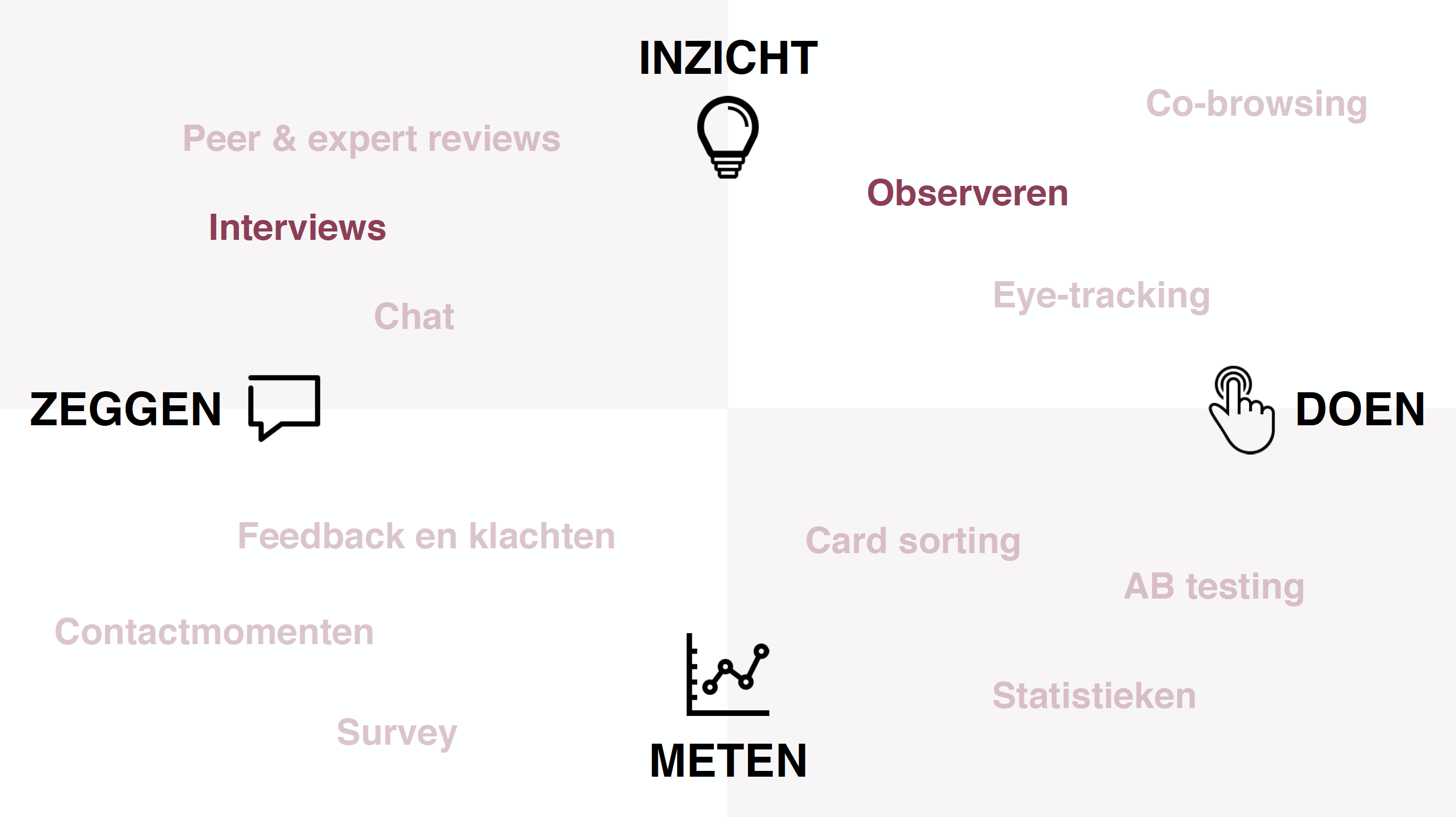

When working with your target audience, don’t just ask what “they think about it. What someone says is not always what someone thinks or feels, let alone does. Behavior and feelings can sometimes be difficult for someone to put into words, if we can get a good handle on them at all. Use a wide range of research methods where you alternate interviews and observations.

Vary the nature and frequency with which you involve your target group. How you organize collaboration, who you involve and what approach you choose, depends on the type of project and the phase you are in. If you are still in the exploratory phase, organize a round table to share current experiences or spend a day in someone’s own context. Do you already have sketches of possible solutions? Then organize targeted user tests like I did with the CoronaMelder.

Want more inspiration to engage your target audience? I talk all about it in the podcast Rich in Behavioral Insights:

Continue reading?

What is human-centered design? All the principles and activities based on the ISO standard at a glance.

Principle 1: Assume the whole experience of your target audience.

Principle 2: Understand users, tasks and environments.