With increasing talk of algorithm supervision, it is important to know how a third-party study of algorithms can be conducted in government. Preferably in such a way that day-to-day implementation processes are not disrupted but according to the principle that government shows itself.

Since January, I have been working with a very nice group to design a work method for this. We focus mainly on the fixed, ‘dumb’ algorithms and not yet on self-learning algorithms. In this blog, a behind-the-scenes look at our approach, initial observations and two questions for you.

I can just see it

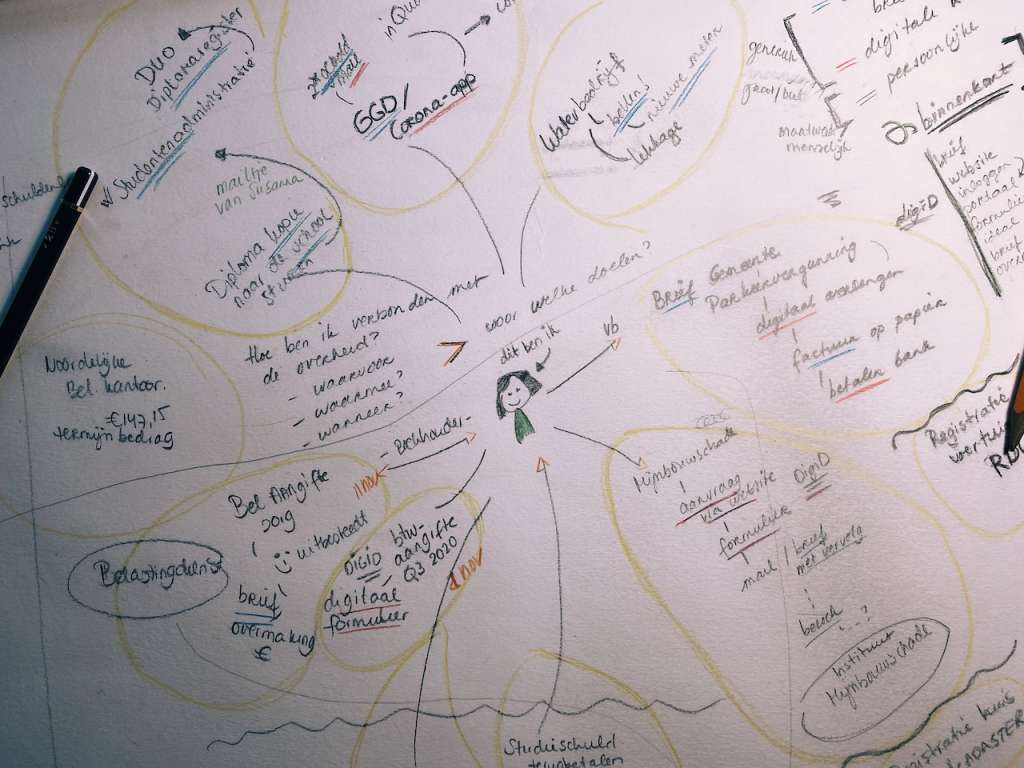

When I had just finished the study The compassionate civil servant, I was sitting with Marlies van Eck on a terrace in Utrecht toasting. She mentioned that she had a follow-up idea to her dissertation (on legal protection in automated chain decisions). Her main conclusion was that, as a lawyer, she could not say whether citizens were sufficiently protected because she could not see the algorithms. The government was a black box, so how can you test whether the decisions it makes are right?

Over my beer I said “but, how weird, because at the Executive Agency of Education, where I worked, I can just see them’. Of course, I immediately began to doubt myself when I said that, but I looked up the photo interview of Cees-Jan talking about decision rules from which the code is then derived. And I mentioned that we were also working to derive the calculation tools on duo.nl from these decision rules so that, as a student, you can simulate how the computer will decide in the future how to pay off your student debt.

Opening and viewing

I am reminded of our conversation frequently because “being able to see the algorithm” is central to this research.

Marleen Stikker writes in her book The Internet is Broken that you only really own something when you can open it up to fix or change it. If you can’t, as with most contemporary technology, the device owns you. Can we open up government’s computers and see how they decide and possibly change that if necessary?

This area is still relatively unknown. The Dutch Tax Service has developed a method for making algorithms testable and explainable. The State Audit Office and accounting firms are preparing for this new task. The General Audit Office has developed a review framework. Recently, the State Council issued a report on automated law enforcement, among other things.

But what is suitable for a financial expert may not work for a researcher who wants to do a legal check. It is also tedious for an implementing organization when different disciplines and organizations consider the use of algorithms at different times and burden the implementation with questions. Both for researchers, and for implementing organizations, a more integrated approach is important.

Say no more. So with a group that I spontaneously get imposter syndrome from, we started in January to experimentally design a method for this. The group: Marlies van Eck, Steven Gort, Abram Klop, Robert van Doesburg, Mariette Lokin, Carlijn Oldeman, Giulia Bössenecker and me. Colleagues from the Executive Agency of Education and the Social Secutiry Bank are cooperating and offering us their automated decisions as trial material to design the method on.

What we want to achieve

Allright. We want to develop a working method for conducting third-party research on a government organization’s use of algorithms. To this end, we have formulated a thought scheme:

- We study how the use of algorithms can be examined simultaneously legally, financially and model-wise[topic].

- because we want to know which discipline would like to see which research questions answered[rationale].

- so that we understand the least burdensome approach to a multidisciplinary and comprehensive assessment[significance].

To keep the research sufficiently concrete but also manageable, we propose that the working method should meet the following four objectives:

- the working method allows a lawyer to make a judgment on the legality and propriety of the system,

- the working method allows a data scientist/ information scientist to make a judgment about the quality of the system,

- the working method enables an accountant or internal controller to make a judgment about …[to be completed, see also help question at the end of this blog],

- the working method is suitable for repeated use in various public organizations.

Designing the method

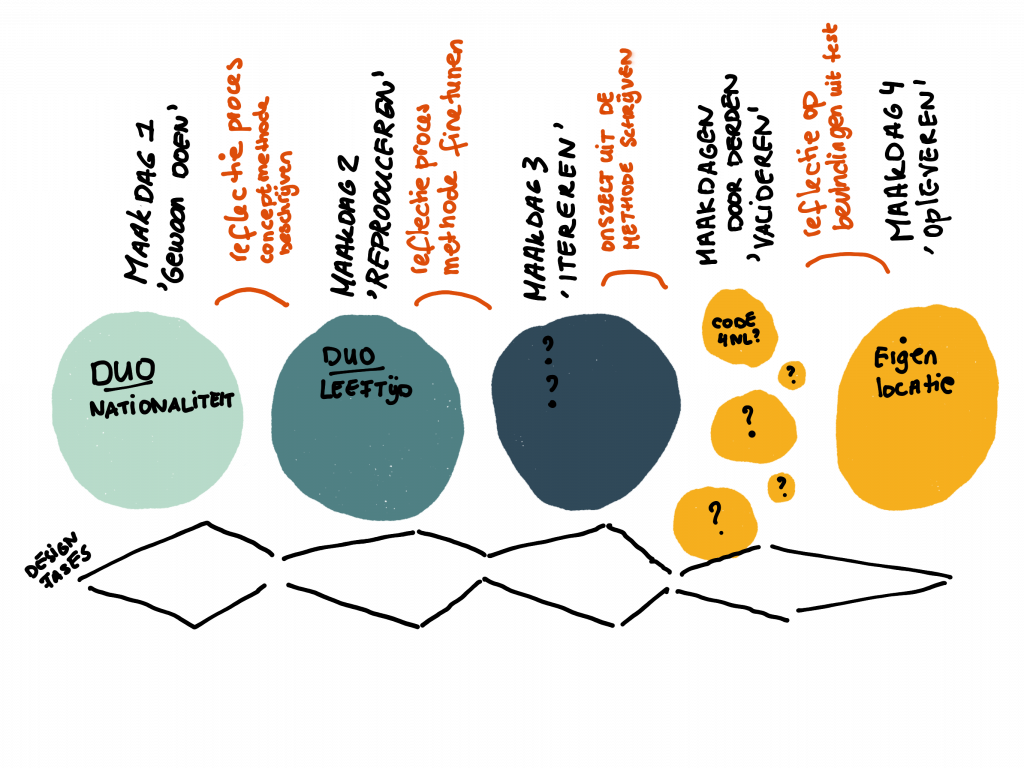

In a series of on-site making days, we will work with a government organization. Lucky for me: the first 2 making days are at the Executive Agency of Education in Groningen where I live.

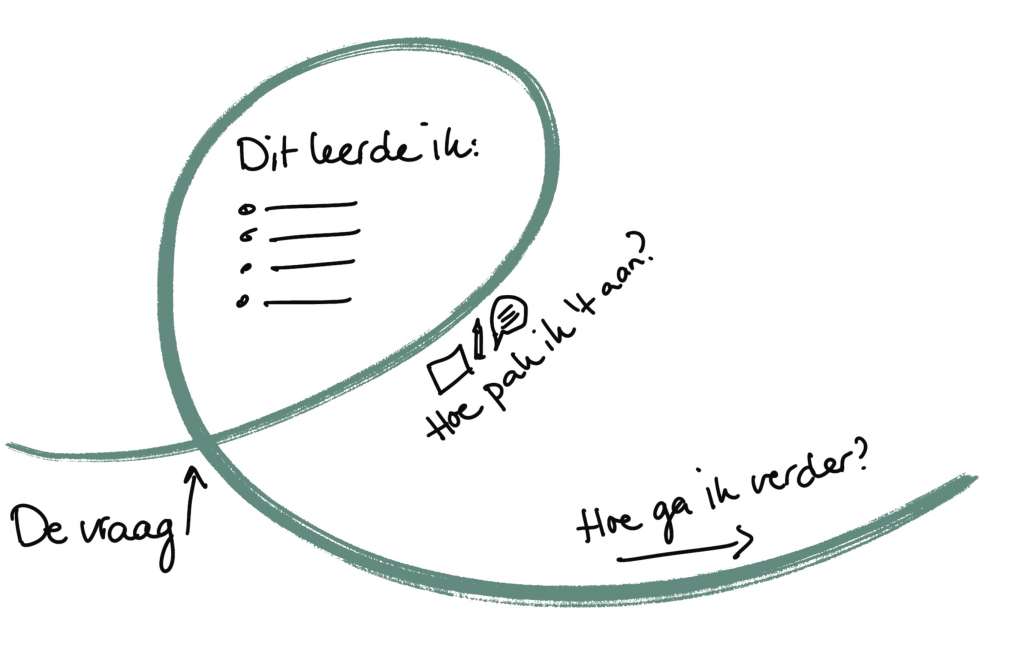

To arrive at a working method that can stand on its own within a few months, we take an embedded and iterative approach. But we must remember to design ourselves out of the method as well, and thus critically examine our bias. We learn by doing: we dive into an algorithm and record our process. Then we reflect on our process and make it explicit. What comes out of this is potentially the method we want to develop.

This is how we shape the creation process:

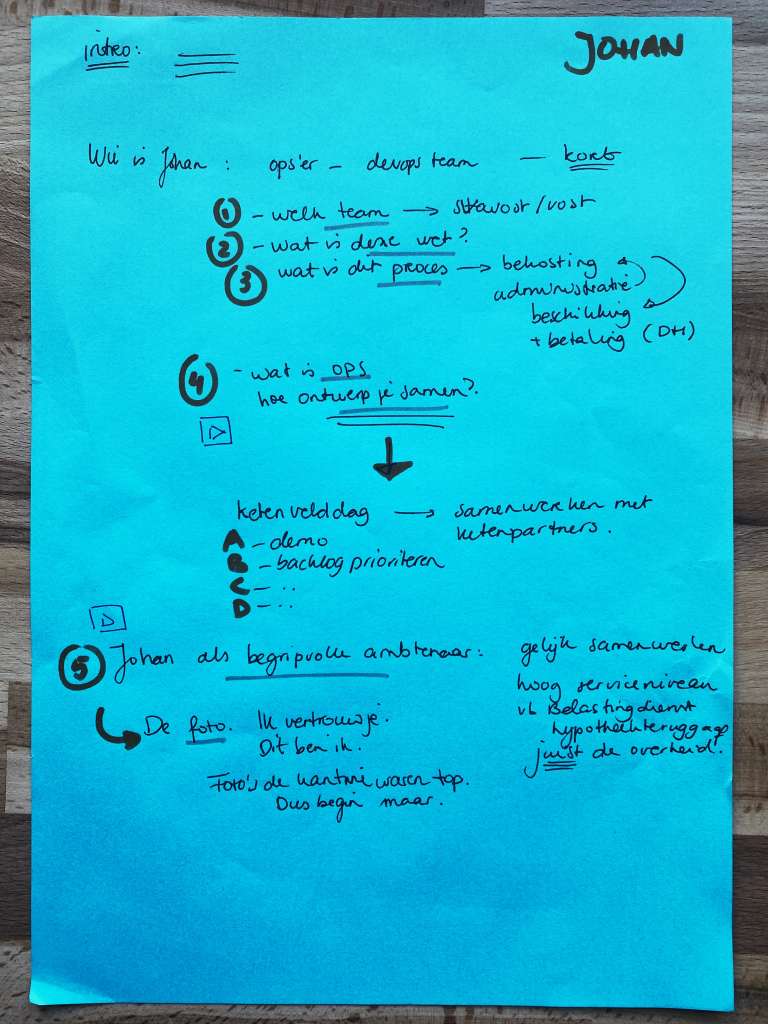

Together with the Executive Agency of Education, we chose a few automated decisions that are part of the big decision whether or not a student will receive a student loan: the nationality test, the age test and the partner test. Beforehand, we were given the sets of decision rules of these three tests to study firmly.

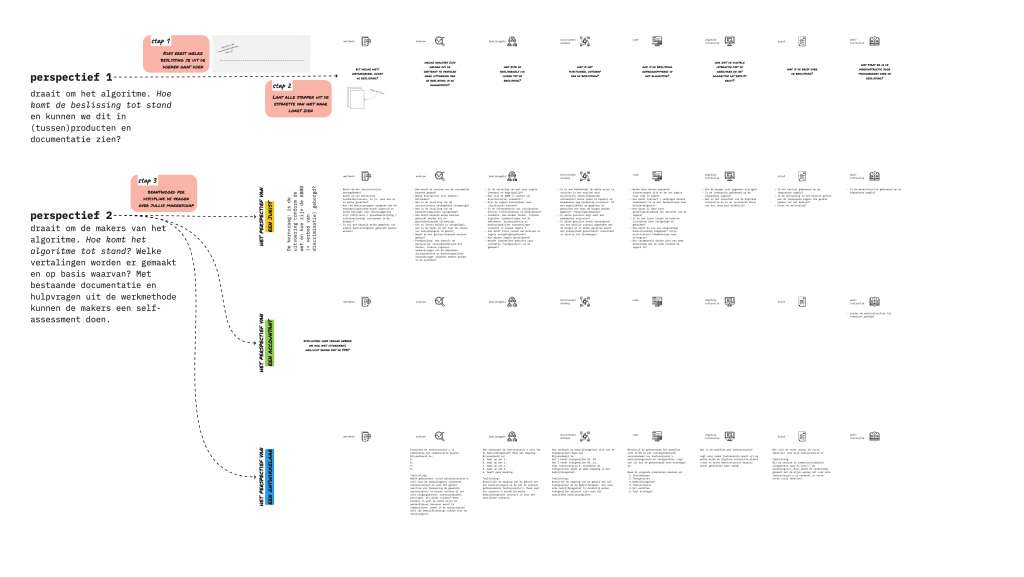

We decided to look from three perspectives or levels of abstraction. Different questions are important for each perspective.

Perspective 1 is the algorithm itself. How does the decision come about?

- What are the decision rules dealing with the nationality test?

- What sections of the law are the decision rules based on?

- How are the decision rules programmed?

- How are they included in the work instruction?

- What data is needed and what are sources?

- How is the decision explained to the student (user) in personal and general communication?

- What interaction does a student (user) have with the algorithm and how does this influence the decision?

Perspective 2 is the creators of the algorithm. How does the algorithm come about?

- Who (what roles and also individuals) are involved in the creation of the algorithm?

- What considerations were made in the creation of the decision rules?

- On what basis do these individuals make these trade-offs? What personal bias is there?

- Is there documentation of this creation, and if so, what is recorded here and for what purpose?

- What is implicit and difficult to make explicit here? In other words, what do we not know (yet) or cannot know (anymore)? How does this come about?

Perspective 3 is ourselves, the supervisors so to speak. How does the method come about?

- How did we proceed? What questions did we ask? What worked well and what didn’t?

- Which questions belong to which discipline (lawyer, accountant and information scientist)? Is there any overlap? Were all disciplines able to get their answers? How do they reinforce each other?

- What knowledge and expertise do we have that allows us to ask these questions?

- Can we reproduce our process next time? What would be different?

‘How crazy it is here’

The first day of making was wonderfully chaotic. We were flying in all directions, asking all kinds of questions, and Jean and Cees-Jan from the Executive Agency of Education were infinitely patient to answer all questions. Sometimes we ended up in heated discussion about the way the organization was organized, only to conclude after an hour that that shouldn’t matter at all for the method. Or as Steven so aptly noted, “I couldn’t care less how it is put together.” :’)

After this day of making, Marlies wrote a first blog with her observations and I made a video for the scientific guidance committee and the sounding board group.

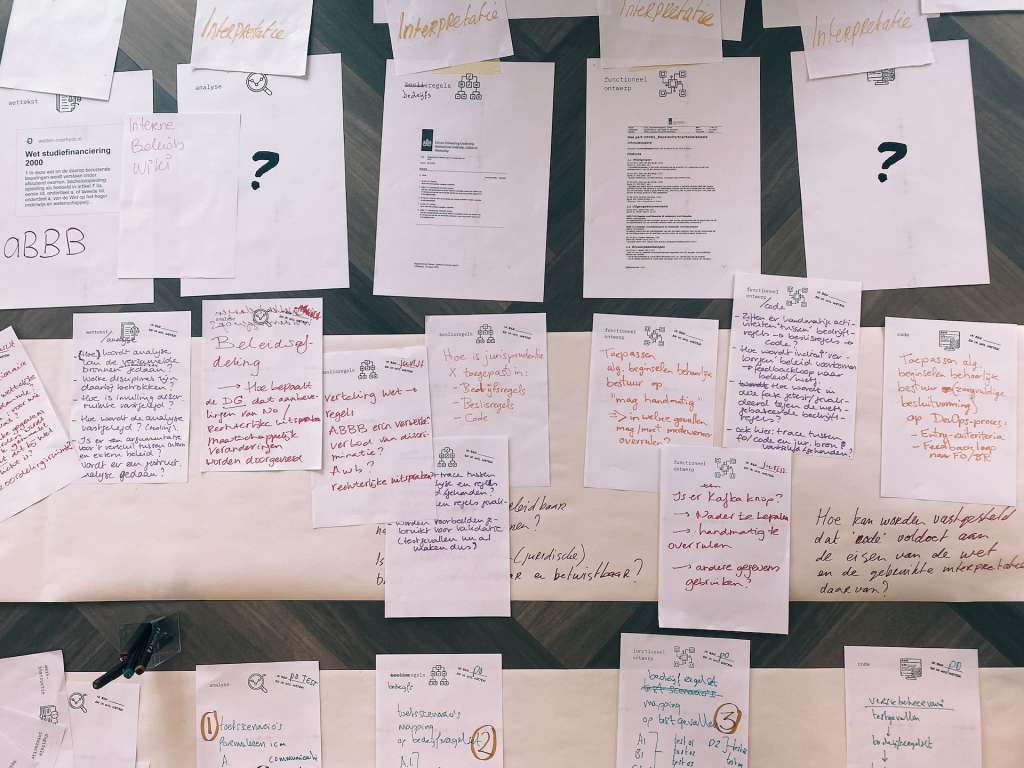

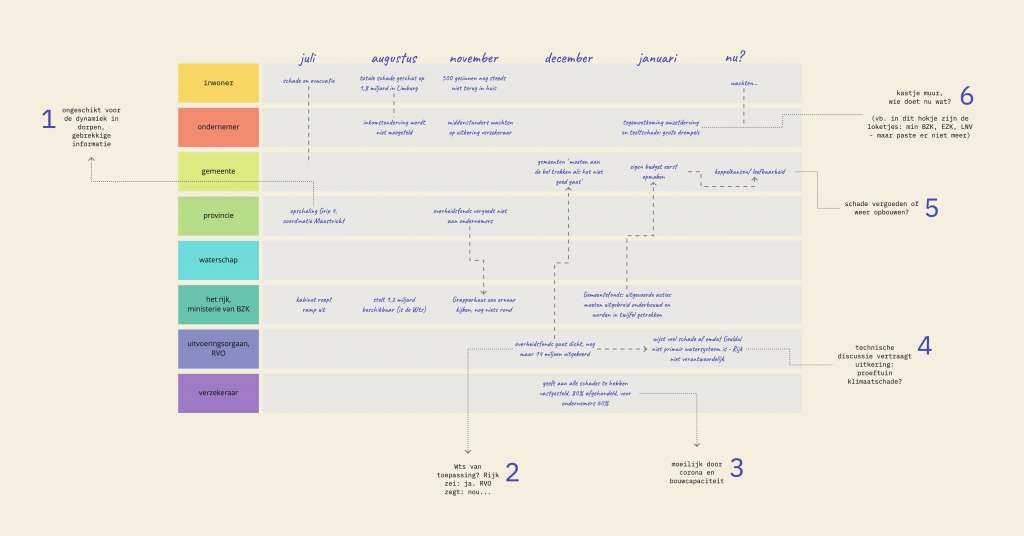

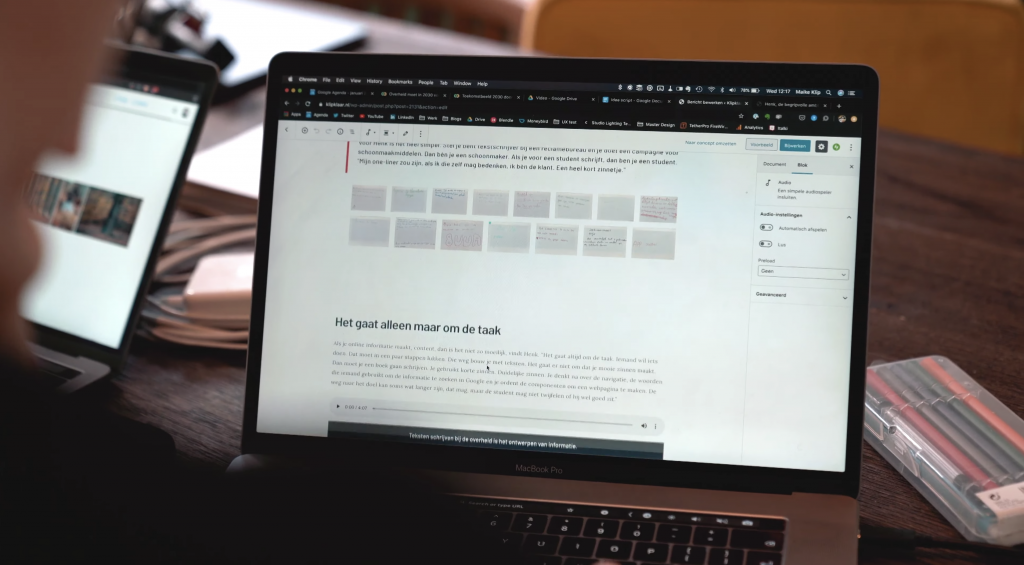

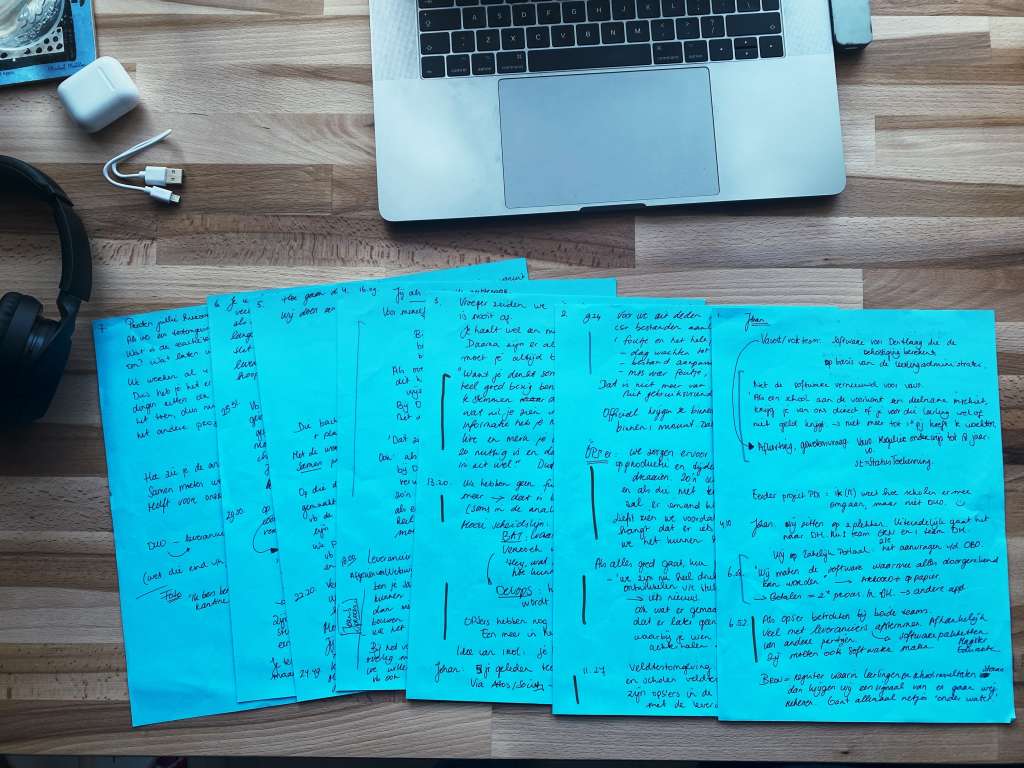

The second day of making went a lot more structured. In preparation, I visualized on a digital board all the steps from law to decision. I asked Cees-Jan if he could fill in everything from another decision (the partner test). This was not so simple because the information and docs had to come from all sorts of nooks and crannies of the organization.

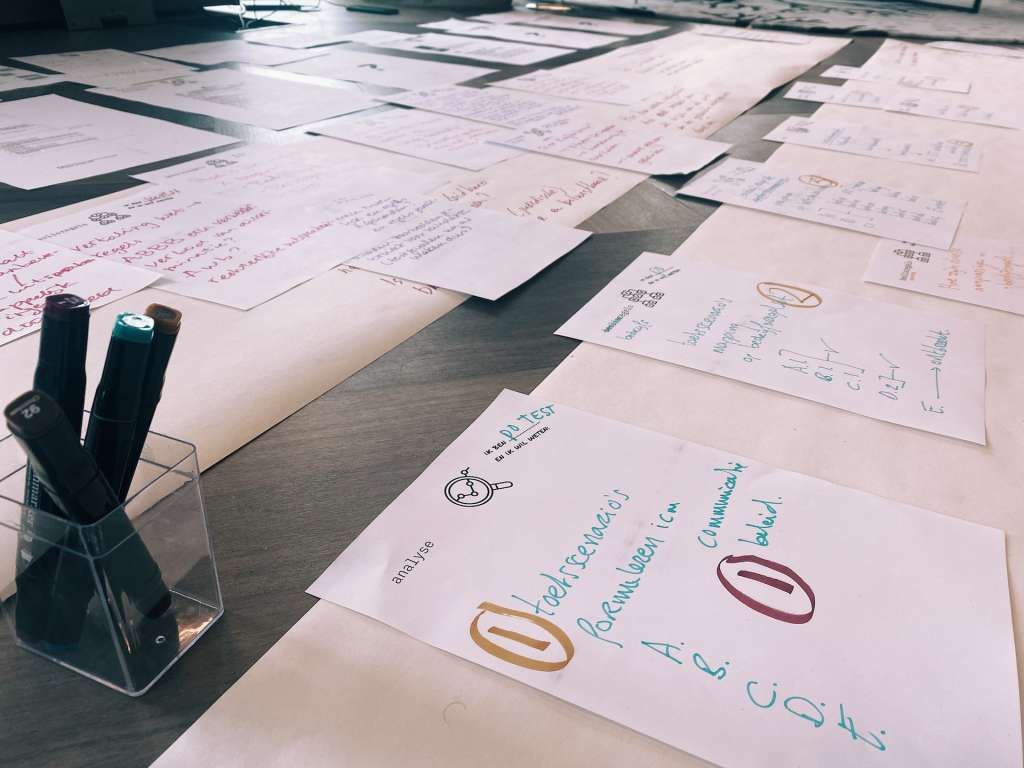

I printed what I got (or left a step open) and put the steps on the floor. Underneath I put 3 long sheets of paper for the questions the lawyer, accountant or developer could ask. Perspective 1 and 3 are below each other. We took all afternoon to fill them out and see if we could get answers directly from Cees-Jan and colleagues (perspective 2).

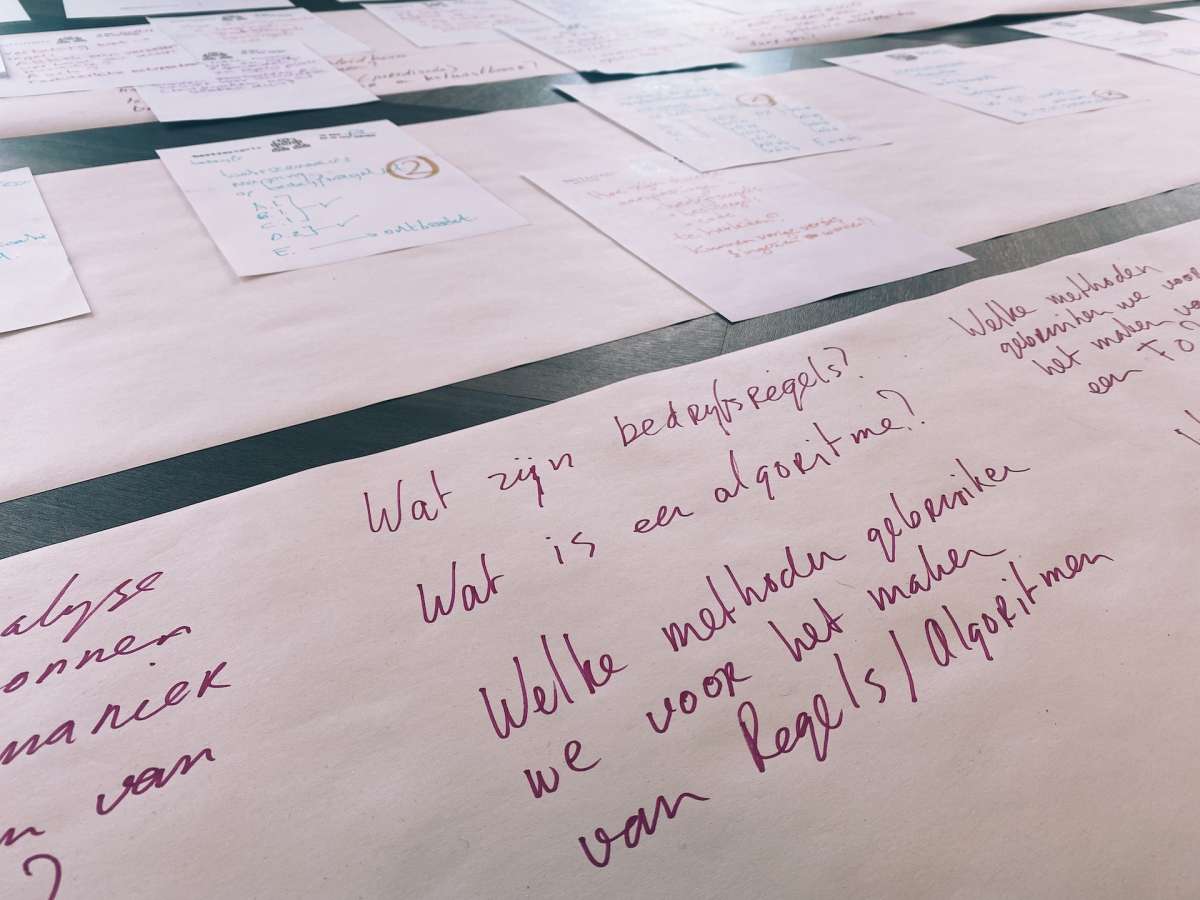

An impression of what that looked like:

In two weeks we will have make day 3 at the Social Security Bank. That will be uncharted territory for me, fun! We are going to look at the age and partner test in the state pension.

In preparation, I digitized the large board we made on the ground at the Executive Agency of Education. It became a version with questions and a blank version for the Social Security Bank colleagues to fill in themselves. We are going to test this prototype and see if this is already a tool for self-assessment to show as an organization how your algorithm comes about and makes a decision.

Through this miro board, you can better zoom in on the prototype. You can also post comments here, and feedback is welcome!

Two questions

You can see that the accountant’s perspective has no questions yet. Here we are still searching. Auditors are very busy around February and March because of wrapping up the previous year. So we haven’t been able to include much input from that side. Do you know more about this or know someone who can help, let me know.

And of course: feedback in general. In this blog, I describe our making process and show the prototype. I’m curious what you think of this and how it would work in your organization. After design day 3, we would like to update our prototype and share it with organizations to use without us for self-assessment. So we want to learn from your findings in turn.

If you would like to help with this, please send me a message. You can do so through maike @ klipklaar.nl or the other known ways. Thanks!